Forward guidance is an integral part of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy toolkit, and aims to manage expectations about the future path of the federal funds rate. Forward guidance is understood to affect the economy by signalling the stance of future monetary policy and reducing interest rate uncertainty (Borio and Filardo 2018).

By May 1999, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) policy statements, first introduced in February 1994, became a regular occurrence following each scheduled meeting (Board of Governors 2022a). The FOMC began to actively use them to signal shifts in the future path of the federal funds rate – often referred to as ‘Odyssean forward guidance’ (Campbell et al. 2012). For example, in October 1999, the FOMC stated it was “biased toward a possible firming of policy going forward.” In August 2003, the FOMC indicated that “policy accommodation can be maintained for a considerable period.”

The FOMC’s approach to Odyssean forward guidance has been qualitative at times. However, in other cases since the 2007-09 Global Crisis, the guidance has been tied to a calendar date or to certain macro goals, while increasingly intertwined with (and complemented by) a wide range of balance sheet policy commitments. In January 2012, the anonymised assumptions for the future federal funds rate path of each FOMC participant were added to the quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) (Williams 2013, Caldara et al. 2021, Board of Governors 2022b). The figure, informally known as the ‘dot plot’, provides a quantifiable insight into the FOMC’s projections. This more precise guidance is known as ‘Delphic forward guidance’ (Campbell et al. 2012).

Expectations management to shift the yield curve

Forward guidance aims to move the longer-maturity rates along the yield curve. The expectations hypothesis of the term structure of interest rates suggests that investing in a long-term bond today must yield the same return as investing consecutively in shorter-maturity bonds over the same investment horizon, after accounting for compensation for risk including term risk. Hence, news of an increase in the expected future federal funds rate – if credible – generally ought to push long-term rates up.

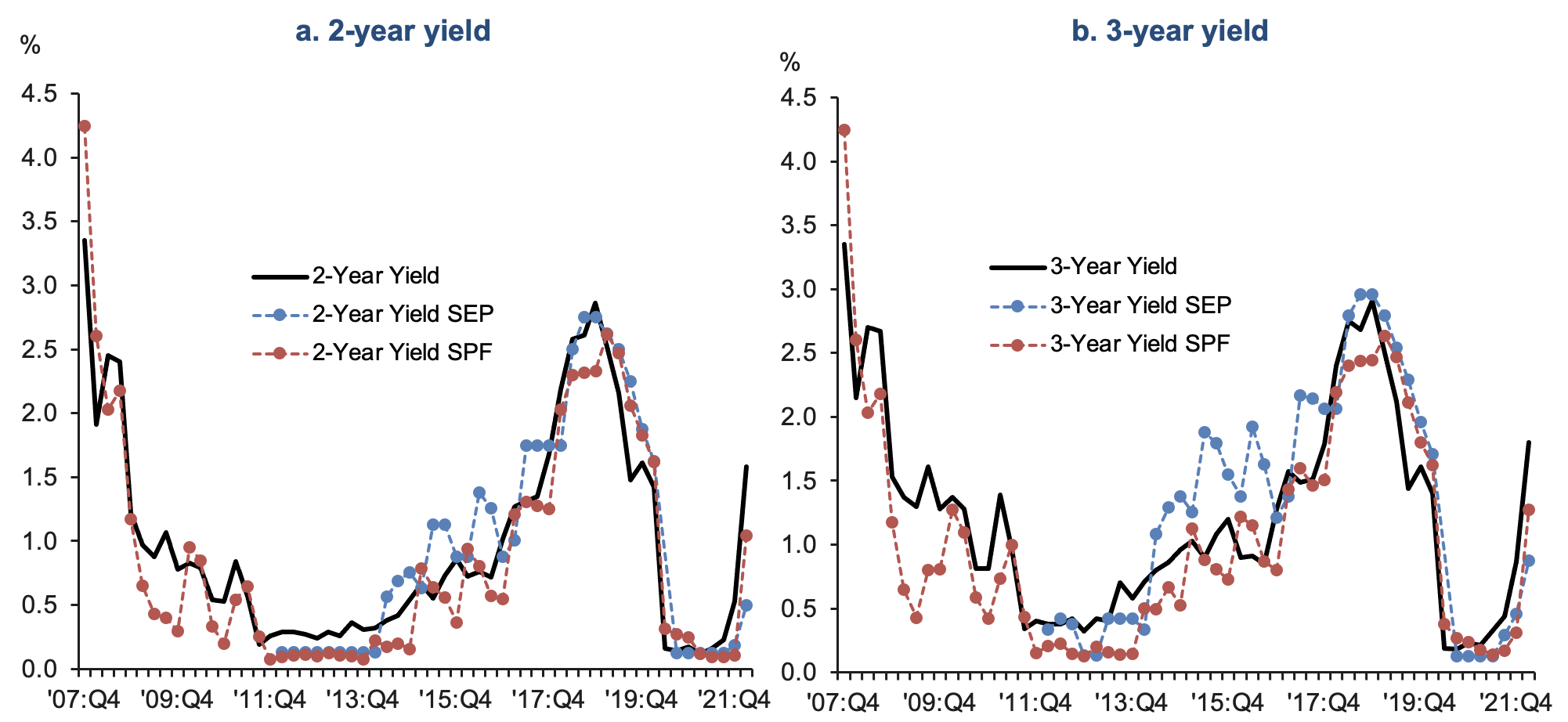

Most policy action in the US since 2007 affected medium-term maturities, notably 2–3-year yields (Figure 1). The yields implied by the median forecast on future 3-month rate reported in the Philadelphia Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) track the observed yields fairly closely, with a modest positive premium over much of this period. For the period of Delphic forward guidance (2012 onwards), we construct the implied yields based on the FOMC’s own median projections for the future federal funds rate.

Figure 1 matches the SPF-implied and SEP-implied yields such that the former are based on forecasts released very soon after the latter’s projections are announced. This illustrates that policymakers had some success in steering the expectations of private forecasters (and, in doing so, also medium-term yields) toward the Fed’s own projections. The discrepancy between the SPF- and SEP-implied yields may occur because the guidance announced is not fully credible to private agents (Haberis et al. 2017, Cole and Martínez-García 2021), but may also reflect differences in the information available to SPF forecasters and FOMC participants.

Figure 1 Some success of forward guidance in managing expectations to shift medium-term rates

Notes: The implied SEP and SPF yields are derived from annual projections under the expectations hypothesis of the term structure. The observed data is matched to the corresponding day of the SPF release while the SEP yield is the one implied by the Federal Reserve's own projections immediately before the SPF release date. Data plotted at quarterly frequency.

Sources: Board of Governors's Summary of Economic Projections (SEP); Philadelphia Fed's Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

The macro effects of forward guidance and the zero lower bound

Private interest rate expectations shocks are quantitatively important but asymmetric depending on whether the federal funds rate is constrained at zero or not (Doehr and Martínez-García 2021a). Away from the zero lower bound, a one standard deviation rise in private interest rate expectations one year ahead leads to a decrease in the unemployment rate lasting for nearly two years, and a very modest fall in core inflation on impact that reverses quickly afterwards (Figure 2). At the zero lower bound, the same shock yields a sustained increase in unemployment and a decrease in core inflation that lasts for over two years.

Figure 2 The impact of interest rate news shocks on the unemployment rate reverses at the zero lower bound

Note: Impulse response function effect of interest rate news shocks on unemployment rate over eight quarters based on a sign-restricted VAR model using median Survey of Professional Forecasts on expected 3-month T-bill rate, core inflation, the unemployment rate, and the federal funds rate. Sign restrictions are motivated by New Keynesian theory (Doehr and Martínez-García 2021a). The period away from the zero lower bound corresponds to 1990:Q1 – 2008:Q3 while the period at the zero lower bound refers to 2008:Q4 – 2015:Q2.

Source: Author's Calculations.

News of a rise in private short-term interest rate expectations raises long-term rates, makes investment less attractive today, increases the current unemployment rate, and lowers inflation. Under traditional monetary policy rules (Taylor 1993), current policy is affected by the resulting economic drag from this anticipated future tightening. Hence, unless policymakers choose to deviate, an expected future tightening can also move the short end of the yield curve.

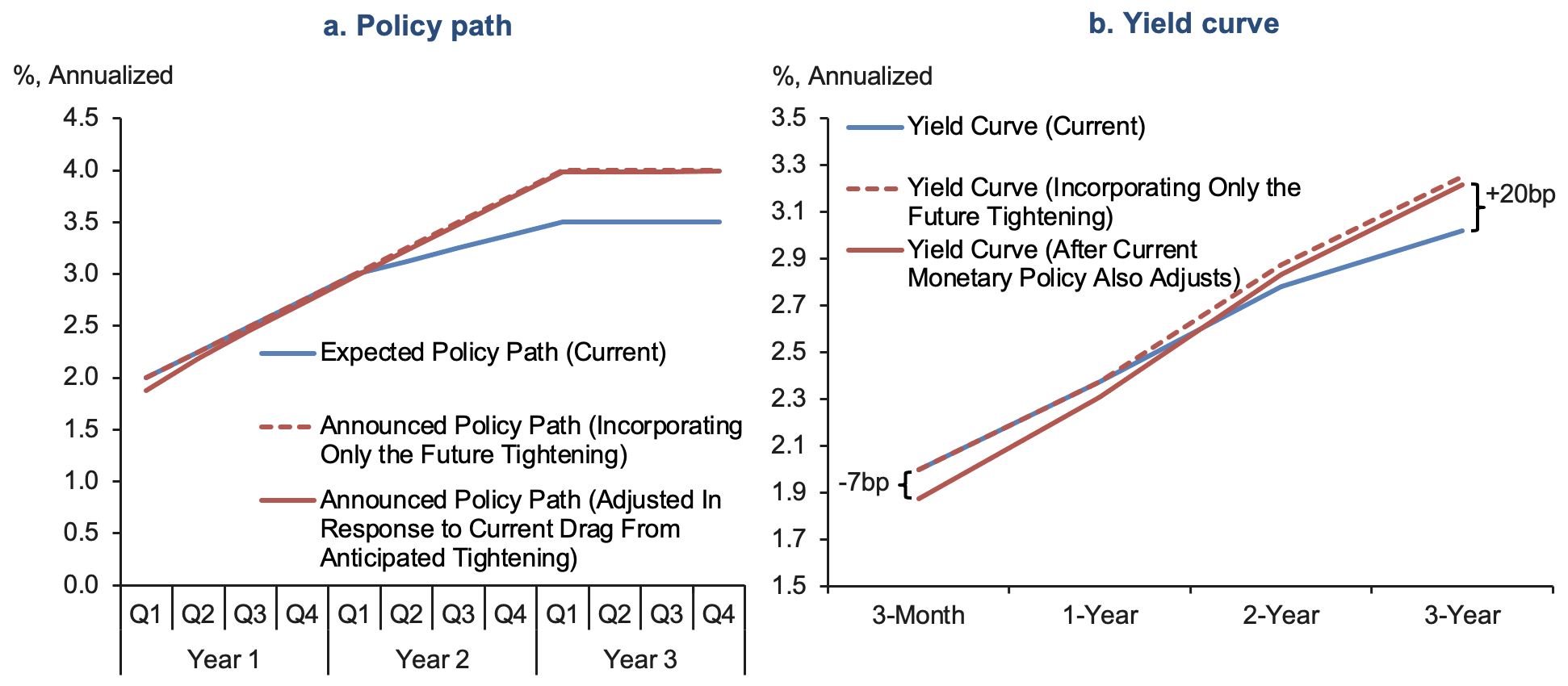

Away from the zero lower bound, current policy à la Taylor would suggest a more immediate accommodating stance to hold shorter-maturity rates down and mitigate, or reverse, the anticipated increase in unemployment and decline in inflation. This allows investors and consumers to substitute, to some degree, longer-term with shorter-term funding and supports aggregate demand. Figure 3A illustrates how a perceived future tightening of monetary policy can increase longer-term yields and steepen the yield curve.

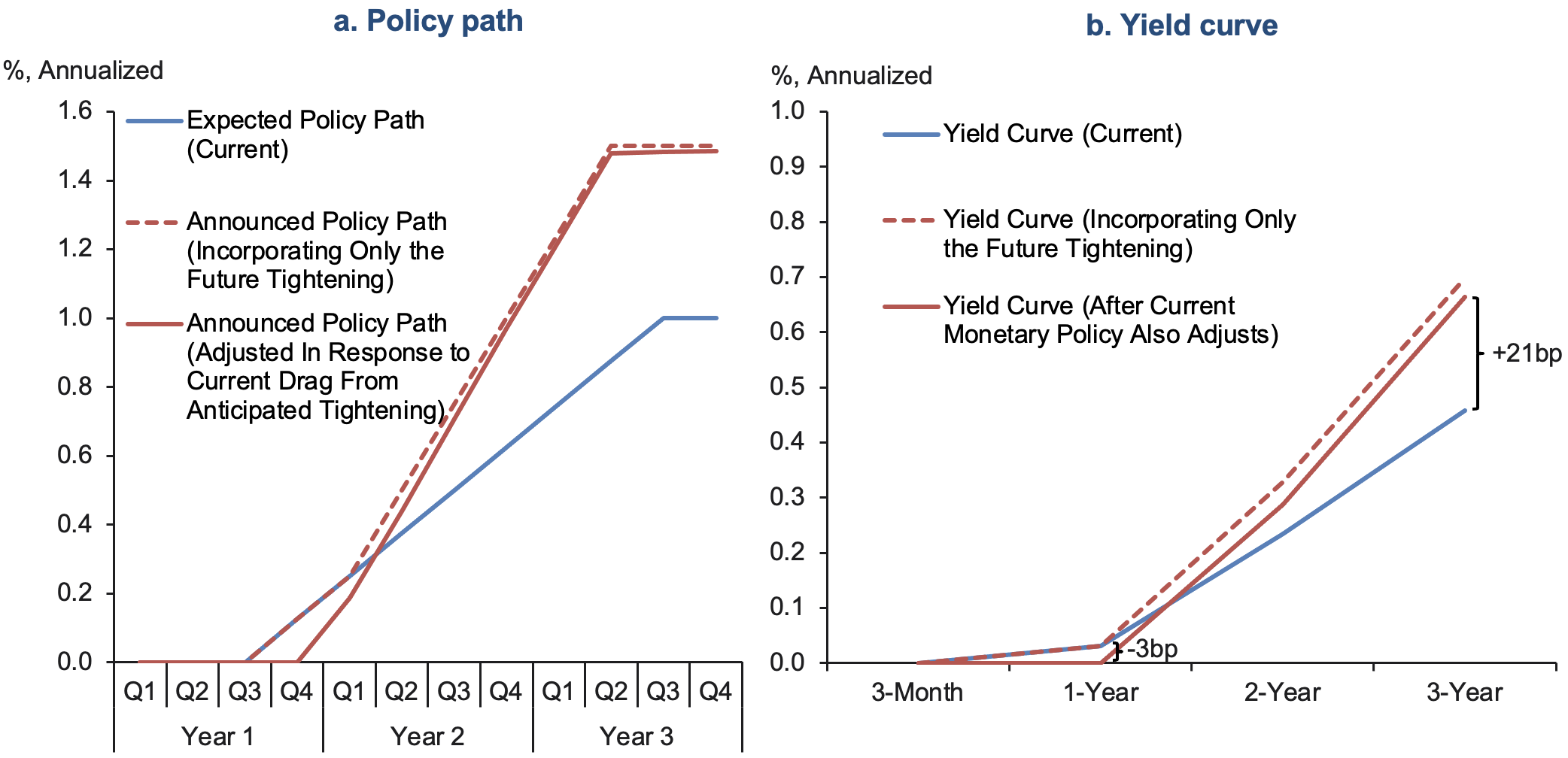

When at the zero lower bound, the initial reaction of private agents to a news shock about tighter future monetary policy is unchanged, but monetary policy cannot dampen the hit because the federal funds rate is stuck at zero and cannot fall. Consequently, the effect of anticipating higher future interest rates leads to an increase in unemployment and a decline in core inflation. Figure 3B illustrates a perceived future tightening increasing longer-term yields while having a largely muted response at shorter maturities in this case, even allowing for the possibility of postponing lift-off.

Figure 3A Forward guidance shifts the expected policy path and yield curve: An illustration

Note: The implied yields on the right-hand subplot are derived from the corresponding path of the policy rate in the left-hand side subplot under the expectations hypothesis of the term structure. The relation between a policy path and a yield curve is indicated with the color and dash type of the lines.

Source: Author's Calculations.

Figure 3B Forward guidance shifts the expected policy path and the yield curve at the zero lower bound: An illustration

Note: The implied yields on the right-hand subplot are derived from the corresponding path of the policy rate in the left-hand side subplot under the expectations hypothesis of the term structure. The relation between a policy path and a yield curve is indicated with the color and dash type of the lines.

Source: Author's Calculations.

Monetary policy uncertainty and expectations management

The effects of forward guidance announcements signalled to private agents worsen if firms choose to postpone investment decisions in response to heightened interest rate uncertainty. In other words, the strength of the signal about the future path incorporated into today’s longer-term yields depends both on the clarity of communication and the credibility of the announced policy commitment. Otherwise, greater uncertainty can become a drag on aggregate demand.

US evidence shows that higher interest-rate uncertainty makes forward guidance shocks less effective on unemployment and core inflation (Doehr and Martínez-García 2021b). Low interest-rate uncertainty can therefore better insulate financial markets and the economy from other non-policy-related news shocks. This benefit of forward guidance has been noted by Filardo and Hofman (2014), among others.

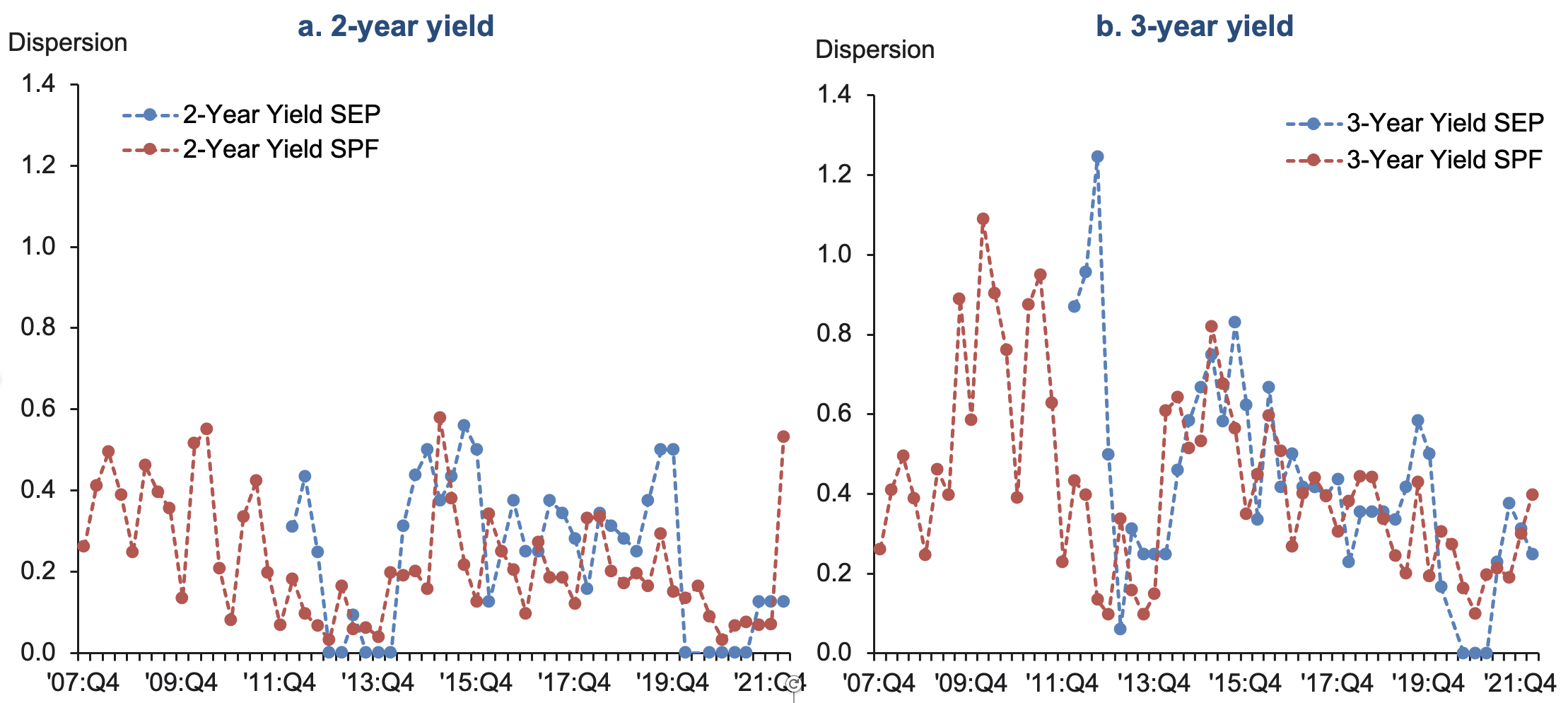

Figure 4 illustrates the strong correlation of the forecasting disagreement, a well-known uncertainty proxy, on medium-term yields implied by the SPF forecasts and the Fed’s own SEP forecasts at the 2–3-year horizon. Greater consensus among policymakers transmitted to the public tends to reinforce the credibility of the announced path and lowers the private forecasters’ own uncertainty. The Federal Reserve has been more successful recently at keeping interest rate uncertainty low as it prepares to lift-off rates, in comparison to its policy actions in 2015.

Figure 4 Disagreement among policymakers and private forecasters correlates strongly, proxies policy uncertainty

Note: Dispersion is measured as the interquartile range of the panel of private forecasters (SPF) and FOMC participants (SEP) respectively. The implied SEP and SPF yields are derived from annual projections under the expectations hypothesis of the term structure for each panelist. The observed data is matched to correspond to the day of the SPF release while the SEP yield is the one implied by the FOMC's own projections immediately before the SPF release date. Data plotted at quarterly frequency.

Sources: Board of Governors's Summary of Economic Projections (SEP); Philadelphia Fed's Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

What policy options are there?

Monetary policy brought down real rates to support the economy’s recovery from COVID-19, but during 2021 real rates have eroded to historic lows as inflation has rapidly climbed (Figure 5). Tightening policy is consistent with the Fed’s new flexible average inflation targeting framework (Martínez-García et al. 2021), as continued monetary accommodation risks fuelling more inflation and de-anchoring long-run inflation expectations.

Figure 5 US short-run and long-run real three-month rates have fallen to historical lows during the pandemic, after being on the decline since before the 2007-09 Global Crisis

Note: The short-term real rate is computed as the three-month yield minus expected inflation one quarter ahead while the long-term real rate is the five-year average three-month real rate, five-years forward. Data plotted at monthly frequency.

Sources: Blue Chip Economic Indicators; Author's Calculations.

The Federal Reserve’s prior experience managing expectations at the zero lower bound offers clues to today’s lift-off and removal of accommodation. News of a tighter monetary policy in the future can help quell inflation today. However, this may be counterproductive once policy rates start to rise, given the evidence of asymmetric responses to interest rate shocks.

One way to avoid this is to start tightening sooner as an earlier lift-off would raise short-term as well as long-term yields. Frontloading the increase in the federal funds rate would further raise short-term yields and help restrain inflation with a bigger punch – albeit at a likely more severe cost in terms of employment. Frontloading largely negates the possibility that aggregate demand can be supported by shortening the duration of liabilities since shorter yields are increasing substantially too.

Finally, effective communication of monetary policy can mitigate the consequences of jarring movements in expected interest rates and can prevent spikes in policy uncertainty while better supporting the economy. Hence, communication and transparency are perhaps more needed than ever before at a key moment such as now.

Conclusion

From a risk-management point of view, failing to account for what we have learned about the signalling and uncertainty channels of forward guidance announcements can have unanticipated (and undesired) consequences on economic activity and inflation as policy rates begin to lift-off. Forward guidance remains a valuable arrow in the Fed’s quiver, so careful expectations management and communication will be key to achieve a smooth lift-off and to tame inflation.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are our own and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the Federal Reserve System, Point72 Asset Management, nor anyone else.

References

Board of Governors (2022a), “Federal Open Market Committee. Background on Policy Statements”, Federal Reserve, press release.

Board of Governors (2022b), “Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications”, Federal Reserve, press release.

Borio, C and A Zabai (2018), “Unconventional Monetary policies: A Re-appraisal”, in P Conti-Brown and R M Lastra (eds), Research Handbook on Central Banking, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Caldara, D, E Gagnon, E Martínez-García and C J Neely (2021), “Monetary Policy and Economic Performance Since the Financial Crisis”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 103(4): 425-460.

Campbell, J R, C L Evans, J D M Fisher and A Justiniano (2012), “Macroeconomic Effects of Federal Reserve Forward Guidance”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2012(1): 1-80. Project MUSE.

Cole, S J and E Martínez-García (2021), “The Effect of Central Bank Credibility on Forward Guidance in an Estimated New Keynesian Model”, Macroeconomic Dynamics 1-39.

Doehr, R and E Martínez-García (2021a), “Monetary Policy Expectations and Economics Fluctuations at the Zero Lower Bound”, Globalization Institute Working Paper 240.

Doehr, R and E Martínez-García (2021b), “Monetary Policy Uncertainty and Economic Fluctuations at the Zero Lower Bound”, Globalization Institute Working Paper 412.

Filardo, A and B Hofmann (2014), “Forward Guidance at the Zero Lower Bound”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Haberis, A, R Harrison and M Waldron (2017), “The Forward Guidance Paradox”, VoxEU.org, 21 September.

Martínez-García, E, J Coulter and V Grossman (2021), “Fed’s New Inflation Targeting Policy Seeks to Maintain Well-Anchored Expectations”, Dallas Fed Economics, April 6.

Taylor, J B (1993), “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 39: 195-214.

Williams, J C (2013), “Forward Policy Guidance at the Federal Reserve”, VoxEU.org, 16 October.