Central banks often make statements about the likely future path of interest rates by providing so-called forward guidance. Forward guidance is especially used if the central bank can no longer cut policy rates because they are already as low as possible (i.e. they have reached their lower bound). In this case, central banks can further ‘ease’ monetary policy by managing expectations about the future course of policy rates.1 Via forward guidance, central banks provide additional information regarding their likely response to economic developments, which can anchor expectations about future policy rates and reduce uncertainty.

The type of forward guidance matters

Forward guidance can be implemented in different ways. Three types of guidance have been dominant in the recent past:

- Open-ended forward guidance is a purely qualitative statement about the policy path. An example is the ECB’s statement used between July 2013 and January 2016 that “we expect the key ECB interest rates to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time”.

- Data-based forward guidance outlines a policy path conditional on economic outcomes. The ECB’s current forward guidance, for example, contains such an element, as the key policy rates are expected to remain at their present levels “for as long as necessary to ensure the continued sustained convergence of inflation to levels that are below, but close to, 2% over the medium term”.

- Calendar-based forward guidance is a policy path with an explicit reference to a calendar date. An example is the current guidance by the ECB, that key policy rates are expected to remain at their present levels “at least through the first half of 2020”.

Do these different types of forward guidance have the same effect? The ECB examples show that central banks have used different types of forward guidance over time – sometimes in combination. Understanding the differences between the different types of forward guidance is important to optimise its use in the future.

In a recent paper (Ehrmann et al. 2019), we study the different ways in which forward guidance has been implemented over time and by different central banks. We focus on the effect of forward guidance on the uncertainty about the future path of interest rates. As forward guidance provides market participants with more precise information on the likely future path of interest rates, we would expect that market interest rates are less responsive to macroeconomic news than in the absence of forward guidance, and that disagreement across forecasters is reduced.

Indeed, the responsiveness of two-year government bond yields to macroeconomic news differs significantly across forward guidance types. Figure 1 highlights this, based on data from six advanced economies during periods where policy rates were close to the effective lower bound.

Open-ended forward guidance has no noticeable effect: government bond yields respond to news in a similar way as in times without forward guidance (marked by the vertical red line). In contrast, data-based forward guidance mutes the responsiveness, a finding that is consistent with the design of this type of forward guidance: markets should update their expectations about the future path of interest rates if there is news about the economic variable that is underlying the state contingency, whereas they should not respond much to other news.

Calendar-based forward guidance with a long horizon has the strongest effect, almost completely eliminating any responsiveness to news, suggesting that market expectations are strongly anchored. However, the results for calendar-based forward guidance with a short horizon are surprising: the responsiveness is amplified substantially, suggesting that in these cases markets perceive a large degree of uncertainty about where interest rates will be heading, larger even than in the absence of forward guidance. In short, the kind of forward guidance matters.

Figure 1 Responsiveness of government bond yields to macroeconomic news under different forward guidance (FG) regimes

Notes: The figure reports the extent to which daily two-year government bond yields respond to macroeconomic news about business confidence, consumer confidence, CPI, GDP, industrial production, non-farm payroll employment, purchasing manager indices, retail sales and unemployment. The responsiveness is normalised to one in the absence of forward guidance. The sample covers Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, for periods with policy rates at or below 1%, up to November 2016.

Source: Ehrmann et al. (2019).

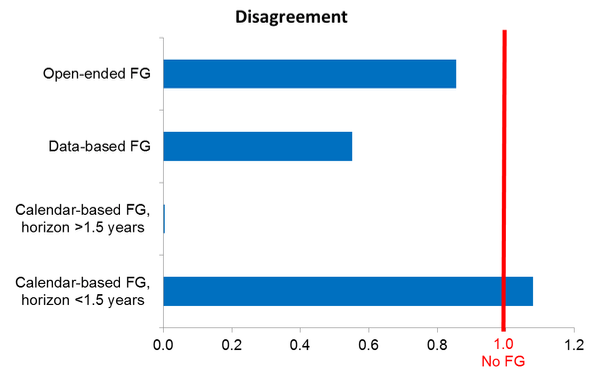

We see a similar picture when we look at the disagreement across forecasters about the future path of short-term interest rates. In Figure 2, there is again no discernible effect under open-ended forward guidance, whereas disagreement is roughly halved in the presence of data-based forward guidance. As with the responsiveness of government bond yields, calendar-based forward guidance with a long horizon exerts the strongest effect – disagreement is effectively eliminated. Calendar-based forward guidance with a short horizon, however, does not reduce disagreement. If anything, it increases it slightly, very much counter to intuition.

Figure 2 Disagreement across forecasters under different forward guidance regimes

Notes: The figure reports the effect of forward guidance on disagreement regarding one-year-ahead forecasts for three-month interest rates, as measured by the interdecile range among Consensus Economics forecasters. The coefficient is normalised to one in the absence of forward guidance. The sample covers Canada, the euro area, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, for periods with policy rates at or below 1%, up to November 2016.

Source: Ehrmann et al. (2019).

How can forward guidance increase uncertainty?

The model developed in our paper explains the counter-intuitive increase in uncertainty under some types of forward guidance. The key ingredient of this model is that there is dispersed information in the economy, and ‘agents’ such as investors can in part learn from observing market prices. In addition to a ‘public’ signal (i.e. a signal that is observed by everyone), each agent receives a ‘private’ signal about the state of the economy (i.e. a signal that is slightly different for each agent) and uses it when forming expectations about future interest rates. Accordingly, this dispersed information gets aggregated into market prices, which consequently reflect information about the economy.

In this setting, forward guidance has two opposing effects on agents’ uncertainty about future interest rates, which affect the sensitivity of government bond yields to macroeconomic news as well as forecaster disagreement. On the one hand, it directly reduces uncertainty, because agents learn more from the central bank about future interest rates. On the other hand, it reduces the informativeness of the private signal relative to the public signal. Agents therefore rely less on the private signal in forming their expectations. While this is optimal for each agent individually, it leads to a situation where less of the information dispersed in the economy is aggregated and reflected in market prices. Therefore, while forward guidance directly decreases uncertainty, it makes prices less informative so that, overall, uncertainty can increase.

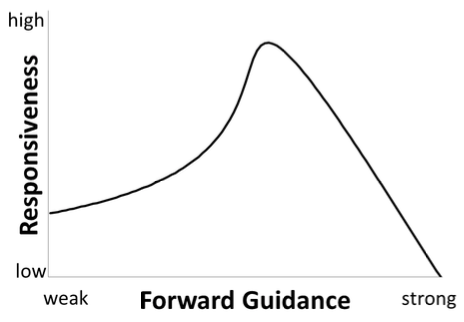

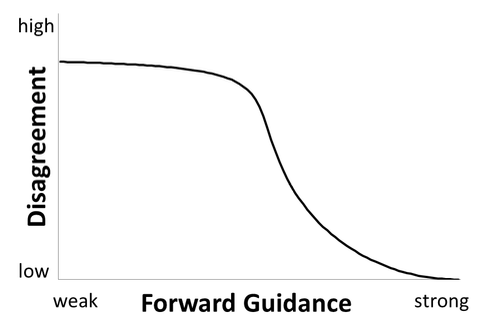

In Figures 1 and 2, calendar-based forward guidance over short horizons can be viewed as a “weaker” form of guidance than calendar-based forward guidance over long horizons. Figure 3, which summarises the key results of the model, suggests that weak forms of forward guidance might indeed generate greater uncertainty and increased responsiveness of market prices to news. Sufficiently strong forward guidance is necessary to reduce uncertainty and the news responsiveness, as only then do the benefits from the additional information provided by the central bank outweigh the losses from reduced price informativeness. Furthermore, weak forward guidance is shown to have only minor effects on the extent of disagreement across economic agents – only if forward guidance strengthens sufficiently, does disagreement drop noticeably.

Figure 3 The effect of forward guidance in a model where agents learn from market prices

Notes: Following the model developed in Ehrmann et al. (2019), the figure reports the effect of varying the strength of forward guidance on i) ex post uncertainty of economic agents, ii) the responsiveness of market prices to macroeconomic news and iii) overall disagreement across economic agents.

Concluding remarks

Forward guidance can provide additional accommodation when policy rates are at the effective lower bound, and also reduce uncertainty. This column suggests that the way forward guidance is implemented matters for its effect on uncertainty. For instance, weak forms of forward guidance, by making market prices less informative, can potentially increase uncertainty. In practice, however, forward guidance is only one part of the central bank’s toolkit, and it is often implemented together with other measures. These other measures can strengthen the forward guidance: further results in our paper show that in the presence of an asset purchase programme, or when the central bank is reinvesting the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under such programmes, all types of forward guidance are sufficiently strengthened and thus reduce uncertainty.

Authors’ note: This column first appeared as a Research Bulletin of the European Central Bank. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of Alberto Martin and Zoë Sprokel. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank, the Banque de France and the Eurosystem.

References

Den Haan, W (ed) (2013), Forward Guidance: Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants, a Vox eBook, CEPR Press.

Ehrmann, M, G Gaballo, P Hoffmann and G Strasser (2019), “Can more public information raise uncertainty? The international evidence on forward guidance”, ECB Working Paper No. 2263.

Endnotes

[1] For a detailed discussion of forward guidance that provides perspectives from central bankers, scholars and market participants, see Den Haan (2013).