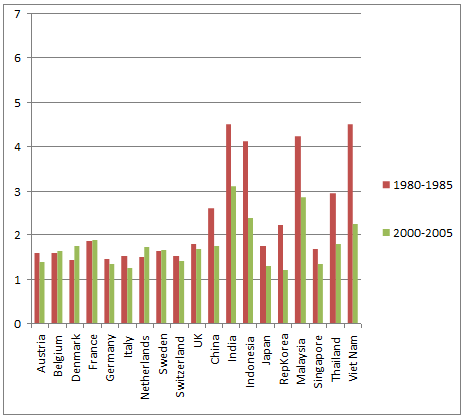

As the realities of an ageing population tick ever closer, policymakers have sharpened their focus on fertility. While low fertility in Europe has been labelled a crisis (Doepke et al. 2008), fertility in some high-income countries of East Asia, such as Japan and South Korea, is even lower. Fertility has also fallen significantly even in rapidly developing middle- and low-income economies, including those of China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam (Figure 1). In China, the personal forces promoting fertility decline reinforce ongoing policies to curb population growth.

Figure 1. Total fertility rates for selected European and Asian countries

Source: International Labor Organization data provided to UNdata (last updated 22 May 2008). The TFR data are estimated averages for five-year intervals in the ILO data.

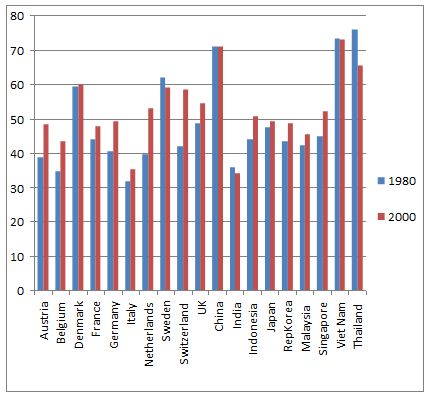

At the same time, female labour force participation rates have generally increased (Figure 2). Soares and Falcao (2008, p.1060) provide striking evidence that increased labour force participation is associated with declining fertility over the past century in the US, the UK, and Brazil. Such empirical evidence, as well as economic theory, suggests a strong link between fertility and female labour force participation, with causality flowing in both directions (Killingsworth and Heckman 1987, Kalwij 2000).

Figure 2. Female labour force participation rates, selected European and Asian countries, 1980 and 2000

Source: International Labor Organization data provided to UNdata (last updated 22 May 2008).

Pinpointing the causal effects

Using data from the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Cramer (1980) argues that “[the] dominant effects are from fertility to employment in the short run and from employment to fertility in the long run” (p.167).

Female employment might lead to lower fertility since working reduces a woman’s available time, and as raising children is time-intensive, employed women might choose to have fewer children. Certainly cities like Hong Kong and Shanghai exhibit both relatively high female labour-force participation and extremely low fertility rates. In Hong Kong, 75% of women in their late 30s are employed while fertility is among the lowest in the world.

But female employment could also lead to higher fertility by boosting family income, thereby making the expenses of childrearing more affordable. In rural China in particular, children – especially sons – are valued for contributing to farm labour and for providing parents with old-age security (Hussain 1994), since pension systems in rural China are only a recent introduction and are nonetheless limited. Indeed, even for high-income Italy the evidence suggests that fertility increases when old-age security decreases (Billari and Galasso 2008).

China’s fertility challenge

Chinese policymakers should be especially interested in the relationship between employment and fertility. China has an enormous population of 1.34 billion and three decades of controversial family-planning policies. The “one-child” policy, introduced in 1979, limits most couples to precisely that. Although fertility rates had already begun to decline steeply before this policy was initiated, the one-child policy appears to have substantially reduced both fertility rates and population growth.

Our recent study (Fang et al. 2010) suggests that policymakers should take into consideration that women’s off-farm employment reduces fertility. We focus on how female employment affects actual and preferred fertility in rural China, using 2006 data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (a stratified random sample from 9 provinces accounting for 44% of the Chinese population). Although not strictly representative of all of China, the data capture a wide range of China’s demographic and socioeconomic diversity.

Our study uses two fertility variables: actual and preferred fertility. Actual fertility is measured as the number of surviving children of a married or previously married woman. Preferred fertility is measured as her actual fertility plus the number she gives in response to the question: If you could choose the number of children to have, how many more children would you want to have? Given the valuable economic role of children – especially of sons, but increasingly of daughters – and the fertility constraints imposed by the state, most rural Chinese women would prefer at least as many children as they have.

We sample well over two thousand married or previously married women between 20 and 52 years old, more than a third of whom are employed in full-time or part-time off-farm jobs. We find that on average women not employed off the farm are each responsible for 1.641 children, and roughly 55% percent have more than one child. By contrast, women with off-farm employment have 1.205 children, with only 22.5% having more than one child.

Table 1. Fertility in rural China by married women’s off-farm employment status, CHNS 2006 sample

|

Actual number of children

|

Unemployed

|

|

Employed

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

0

|

67

|

|

4.618

|

|

|

52

|

|

6.213

|

|

|

1

|

583

|

|

40.179

|

|

|

597

|

|

71.326

|

|

|

2

|

639

|

|

44.039

|

|

|

160

|

|

19.116

|

|

|

3

|

137

|

|

9.442

|

|

|

22

|

|

2.628

|

|

|

4

|

16

|

|

1.103

|

|

|

5

|

|

0.597

|

|

|

5

|

9

|

|

0.620

|

|

|

0

|

|

0.000

|

|

|

6

|

0

|

|

0.000

|

|

|

1

|

|

0.119

|

|

|

Total

|

1451

|

|

100.000

|

|

|

837

|

|

100.000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Preferred total number of children

|

Unemployed

|

|

Employed

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

0

|

52

|

|

3.584

|

|

|

29

|

|

3.465

|

|

|

1

|

481

|

|

33.150

|

|

|

527

|

|

62.963

|

|

|

2

|

721

|

|

49.690

|

|

|

226

|

|

27.001

|

|

|

3

|

165

|

|

11.371

|

|

|

48

|

|

5.735

|

|

|

4

|

19

|

|

1.309

|

|

|

6

|

|

0.717

|

|

|

5

|

11

|

|

0.758

|

|

|

0

|

|

0.000

|

|

|

6

|

2

|

|

0.138

|

|

|

1

|

|

0.119

|

|

|

Total

|

1451

|

|

100.000

|

|

|

837

|

|

100.000

|

|

Dealing with endogenous employment

This raises two questions. How does off-farm employment affect fertility? And is this employment likely to be endogenous? Indeed, the number of a woman’s children has long been recognised as an important factor affecting female labour supply (Killingsworth and Heckman 1987).

We use two instrumental variables to tackle these endogeneity concerns.

- First, whether there is a bus stop in the village where the woman resides.

- Second, the proportion of the workforce in the village that is employed in local enterprises.

The existence of such larger local enterprises reflects the opportunities for women to be hired within their communities, while a bus stop makes it easier for women to work in other villages or towns, thereby boosting off-farm job opportunities. Among women with off-farm jobs, over three-quarters have access to a bus stop in their own villages; among women without such employment, less than two-thirds. Thus, access to a bus stop in the village is strongly predictive of female employment status. Similarly, a higher proportion of the village work force that works in local enterprises with at least 20 employees is also strongly predictive of female off-farm employment.

New insight on the effect of employment on fertility

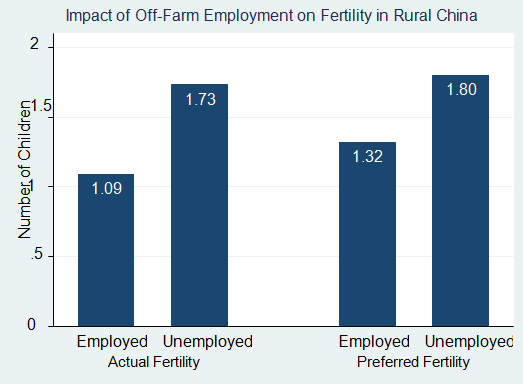

We find that off-farm employment of females reduces both actual and preferred fertility for rural Chinese women. Figure 3 shows that, based on our preferred specification and holding other factors at their sample means, off-farm employment reduces the actual number of children per woman by 0.64 and the preferred number by 0.48. Off-farm employment reduces the probability of having more than one child by 54.8% and the probability of preferring more than one child by 49.6%.

Figure 3. The impact of off-farm employment on fertility of married women in rural China

Source: Authors’ endogeneity-corrected estimates from 2006 China Health and Nutrition Survey data.

Policy implications

In March 2010, China announced an investment of the equivalent of over $6 billion to boost employment, particularly among rural migrants and college graduates (China Daily 2010). Will there be equal opportunities for women in these employment efforts?

Research on Europe suggests that gender inequality in the labour market was a catalyst for the baby boom after World War II (Doepke et al. 2008).

This gender inequality is not an unlikely outcome in the China’s case, raising the possibility of a boom in fertility. Despite Mao Zedong’s famous slogan that “women hold up half the sky”, since 1979 rural Chinese women have been particularly affected by recessions, notably in relation to off-farm employment, even after accounting for women’s lower levels of education than men (Zhang et al. 2002). Meanwhile Dong et al. (2004) report that during the reform period over the last thirty years, women have had less control over their work than men, less of an economic return to work, and much less likelihood of becoming shareholders in newly privatised rural industry.

China has deep concerns regarding both population size and employment. Encouraging more women to pursue off-farm employment could substantially reduce fertility without imposing any of the punishments and penalties for childbearing that have earned China so much criticism. Spending more to educate girls and women would complement pro-employment policies – education is known to further reduce fertility (Becker 1991), while boosting productivity for women and the economy as a whole. The female employment-fertility relationship in rural China points the way to win-win policies.

References

Becker, Gary S (1991), A Treatise on the Family, Harvard University Press.

Billari, Francesco C, and Vincenzo Galasso (2008), “Why do we really have children?” VoxEU.org, 22 October.

China Daily (2010), “China to invest $6.34b to boost employment”, 5 March.

Cramer, James C (1980), “Fertility and Female Employment: Problems of Causal Direction”, American Sociological Review, 45(2):167-190.

Doepke, Matthias, Moshe Hazan, and Yishay Maoz (2008), “More babies for Europe: Lessons from the post-war baby boom”, VoxEU.org, 8 September.

Dong, Xiaoyuan, F MacPhail, P Bowles, and SPS Ho (2004), “Gender segmentation at work in China's privatized rural industry: Some evidence from Shandong and Jiangsu”, World Development, 32(6):979-998.

Fang, Hai, Karen N Eggleston, John A Rizzo, and Richard J Zeckhauser (2010), “Female Employment and Fertility in Rural China”, NBER Working Paper 15886, April.

Hussain, Athar (1994), “Social Security in Present-Day China and its Reform”, The American Economic Review, 84(2):276-80.

Kalwij, Adriaan S (2000), “The Effects of Female Employment Status on the Presence and Number of Children”, Journal of Population Economics, 13(2):221-239.

Killingsworth, Mark R, and James J Heckman (1987), “Female Labor Supply: A Survey,” in , Orley C Ashenfelter and Richard Layard (eds.), The Handbook of Labor Economics, Amsterdam.

Soares, Rodrigo R, and Bruno LS Falcao (2008), “The Demographic Transition and the Sexual Division of Labor”, Journal of Political Economy, 116(2):1058-1104.

Zhang, Linxiu, Jikun Huang, and Scott Rozelle (2002), “Employment, Emerging Labor Markets, and the Role of Education in Rural China”, China Economic Review, 13(2-3): 313-328.