Economists and policymakers tend to believe that the quality of market institutions positively affects economic performance. Because of that, structural reforms are often a condition for fiscal assistance to stressed countries. A package of structural reforms typically includes measures that liberalise a country’s labour market or make it more flexible – making it easier, for instance, to hire and fire workers. Such measures are said to deliver large economic benefits to liberalising countries (Dustmann et al. 2014). There are equally good arguments to suggest that more flexible labour markets will deliver substantial benefits to a country’s economy during downturns, by facilitating ‘creative destruction’ and by allowing firms with good growth prospects to continue growing (Caballero and Hammour 1994). How beneficial is labour market flexibility (e.g. the ability to hire and fire workers) for firm growth during a deep recession? And how does such flexibility interact with a firm’s ability to obtain bank credit?

Based on recent research, in this column we present novel evidence that flexible employment protection law – that is, a flexible labour market – benefits otherwise healthy firms during a credit crunch (Laeven et al. 2018). We demonstrate a robust fact, namely, that credit constrained firms grow faster if they are subject to less strict firing and hiring restrictions, as long as they are technologically able to substitute labour for capital. Our findings are based on data from Spain, a country with structurally high unemployment levels.

Labour regulation in Spain is characterised by well-defined, firm size-specific rules, under which employment protection is notably more stringent for firms with more than 50 employees. There are two rules that concern us here. First, the negotiation period in the case of collective dismissals is twice as long for firms with more than 50 employees, typically resulting in higher severance pay per employee. Second, in firms with more than 50 employees, a collective dismissal has to be accompanied by a social plan to mitigate the consequences for the affected workers. Moreover, such companies also have to carry out a special training and redeployment plan of at least six months, implemented by means of an authorised outplacement company. This implies that the cost of hiring the marginal worker, given that she may have to be fired (or made redundant) in the future, is higher for such firms. As a result, firms facing stricter firing restrictions will be less likely to hire additional workers when they need to keep growing.

The credit crunch of 2008–09 resulted in a sudden and drastic increase in firms’ borrowing costs. Spanish banks were not all equally affected by the crisis, and some required large recapitalisations, of the overall order of 1.1% of GDP. While some of these actions took place right at the start of the crisis, further consolidation operations and the bulk of the nationalisations took place throughout the crisis. During this period, savings banks were forced to transform into commercial banks, and the European Financial Stability Facility provided financial assistance for the recapitalisation of a number of banks. Overall, a total of 71 banks were subject to some kind of intervention. While during the crisis the supply of credit declined across the board, new credit issued by affected savings banks declined significantly more. Weak banks rationed credit by charging substantially higher average interest rates than healthy banks (Bentolila et al. 2018). Firms borrowing from affected banks therefore experienced a larger increase in borrowing rates, giving them a greater incentive to substitute labour for capital in order to keep operating.

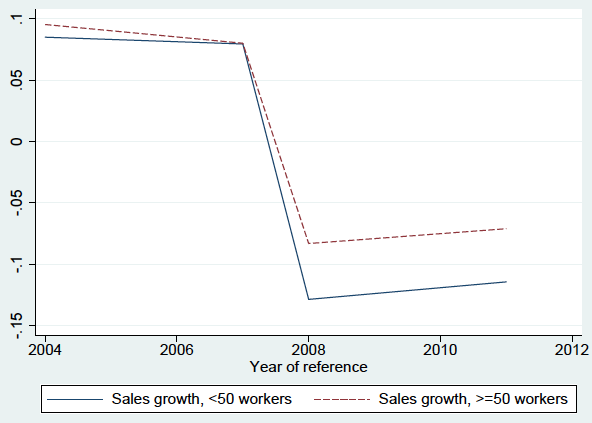

Within the subset of firms that would like to substitute labour for capital, when subject to tightening borrowing constraints and less strict labour regulation, only those that can easily replace capital with labour (i.e. those that exhibit a high degree of substitutability between workers and machines, or ‘high sigma’) will be able to do so. So it is important to identify which firms are able to substitute one of those factors of production for the other. (Our sectoral estimates of the substitution elasticity range from a low of 0.4 for the coke production sector to a high of 2.0 for the construction sector, with a median value of 0.9.) Balance sheet shocks lead banks to reduce credit to their borrowers, and many studies have argued that smaller firms are affected more severely by this process as their investment projects are more opaque and uncertain (Berger and Udell 1995). This firm-size effect would imply that after a shock to their main bank, firms with fewer than 50 employees may suffer more in terms of growth as banks tighten credit relatively more for them. Figure 1 plots growth rates before and after the credit shock for the firms in our sample. It clearly shows that while small and large firms were growing at approximately the same rate up to 2007, once the shock hit in 2008, sales growth declined considerably more for smaller firms. This is consistent with steeper credit constraints for smaller firms.

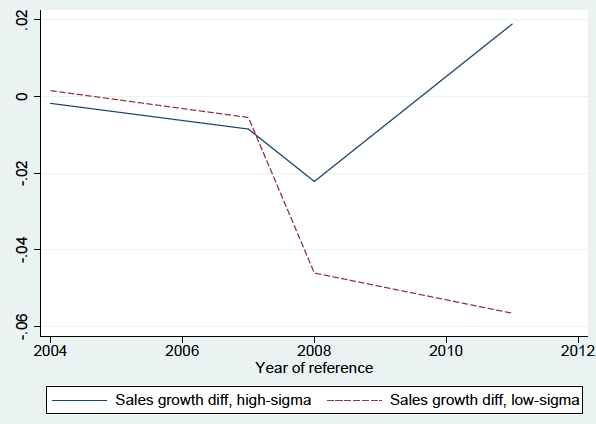

However, Figure 2 demonstrates that this divergence in growth rates is driven by firms in sectors in which capital and labour cannot readily be substituted for each other (‘low-sigma’ sectors). At the same time, for firms in sectors in which they can (‘high-sigma’ sectors), affected firms with fewer than 50 employees post relatively higher growth than affected firms with more than 50 employees. This suggests that in the absence of substitutability between these two factors of production, the firm-size effect can dominate the employment-protection effect, and only firms that can substitute labour for capital will benefit from flexible employment protection laws in the presence of credit constraints.

Figure 1 Difference in sales growth between small and large firms

Notes: High (low) sigma denotes above-median (below-median) estimated elasticity of substitution between capital and labour values. The sales growth figures on the vertical axes are measured in annual percentage differences.

Figure 2 Difference in sales growth between small and large firms, in low-sigma vs. high-sigma sectors

Notes: High (low) sigma denotes above-median (below-median) estimated elasticity of substitution between capital and labour values. The sales growth figures on the vertical axes are measured in annual percentage differences.

The analysis exploits the Orbis dataset containing full balance sheet information for around 110,000 Spanish firms, observed both before and after the crisis, and covering the full size distribution of firms, from 1 employee to over 1,000 employees. The dataset also contains information on bank-firm relationships, making it possible to reliably measure a tightening of credit constraints at the level of the firm by isolating firms with credit relationships with banks that experienced severe balance sheet problems during the crisis. Overall, 26% of the firms in the sample have a credit relationship with one of the 71 Spanish banks that required government intervention during the crisis.

The main finding is that Spanish firms with fewer than 50 employees grew relatively faster during the financial crisis when exposed to a negative credit shock than similarly credit constrained but larger firms in sectors in which labour and capital can be more easily replaced with one another. This result emerges regardless of firm-specific factors, such as cash flows and net worth, which vary over time and can affect firm growth in the absence of credit shocks or firm size-specific labour regulation. It is also apparent when controlling for differences between firms and sectors other than firm size. The main effect is still documented when comparing smaller and larger firms closer to the 50-employee threshold, when other underlying industry characteristics, such as dependence on external finance, are controlled for, and when the sample is restricted to firms with a credit relationship with only one bank. Moreover, firms subject to less stringent employment protection in sectors with high substitutability between labour and capital experience higher rates of employment growth, but not higher investment growth. This confirms the underlying process at work. Crucially, the main effect is much more pronounced for firms with sales and productivity growth that was relatively high before the crisis started. Taken together, these results suggest that flexible employment protection benefits firms faced with an exogenous shock to their user cost of capital, by enabling them to substitute labour for capital and so to continue growing.

The pattern uncovered in the data provides one argument in favour of the adoption of flexible labour laws. While such labour market reforms can be associated with job losses for individuals, in the aggregate they allow firms to recover more quickly from a deep recession whose roots are in the banking sector. Since the financial crisis, Spain has in fact embarked on a package of labour market reforms with a view to making labour markets more flexible and, in particular, easing the cost of dismissals for firms. This has led to a reduction in the wage bill of the average firm and generated an economic recovery and a fall in the exorbitantly high levels of unemployment. For such reforms to succeed overall it is critical that the benefits accruing to firms are shared with dismissed workers, either through job creation or redistribution.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the institutions with which they are affiliated. A similar version of this column previously appeared as an ECB Research Bulletin.

References

Bentolila, S, M Jansen and G Jimenez (2018), “When credit dries up: Job losses in the Great Recession,” Journal of the European Economic Association 16: 650–695.

Berger, A and G Udell (1995), “Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance,” Journal of Business 68: 351–381.

Caballero, R and M Hammour (1994), “The cleansing effect of recessions,” American Economic Review 84: 1350–1368.

Dustmann, C, B Fitzenberger, U Schönberg and A Spitz-Oener (2014), “From sick man of Europe to economic superstar: Germany's resurgent economy,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 167–188.

Laeven, L, P McAdam and A Popov (2018), “Credit shocks, employment protection, and growth: Firm-level evidence from Spain,” CEPR, Discussion Paper 13026.