The risk of living long and facing high medical expenses goes a long way toward explaining the elderly persons’ saving decisions.

Some elderly people enter retirement with vast amounts of wealth and keep most of that wealth even as they approach extremely old ages (see Hurd, 1990 for a review). Others start retirement with precious little and rely on Social Security and other government programmes to finance their consumption. These differences can be seen in a balanced panel of single Americans drawn from the Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old (AHEAD) dataset. For example, the assets of people aged 72-81 and in the top quintile of the permanent (non-asset) income distribution had a median value of $154,400 in 1995. Seven years later, in 2002, median assets for the same group were $142,500, a drop of less than 10%. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 71-81 year-olds at the bottom 20% of the permanent income distribution held only $2,000 in 1995, and had no net worth to speak of in 2002. These tendencies are reinforced by the findings of Dynan et al. (2004), who show that households with high non-asset income tend to save at higher rates.

Why the elderly save and what causes the large differences in their saving rates is a very important policy question, whose answer is likely to influence the design of key government programmes such as public pensions and old-age health insurance. Providing meaningful answers to these questions requires a good understanding of the kind of risks that the elderly face. It also requires that the model used to study these risks be able to explain the observed data and to account for the most important government programmes.

Among the motivations to save at older ages are the desire to insure oneself against the risks of living long and having high medical expenses in old age. Both are likely to be especially strong in the US for two reasons. First, the US government pension scheme, Social Security, replaces only about 45% of pre-retirement income. Second, despite nearly universal health insurance for the elderly through Medicare, many medical services, such as nursing home care, are virtually uninsured.

In recent research (De Nardi et al., 2006, 2009), we quantify the importance of these risks by estimating and simulating a detailed model of saving behaviour. Our work builds upon earlier analyses of life cycle saving by Kotlikoff (1988), Hubbard et al. (1994), Palumbo (1999), Gan et al. (2004) and Scholz et al. (2006). Our model accounts for differences in lifespan and medical expenses across socioeconomic groups, as well as the risk of living especially long and having especially high medical expenses. The model also explicitly accounts for public and private pensions and publicly provided social insurance. The model fits the data well – it matches, among other things, observed differences in saving behaviour across people with different incomes – which gives us confidence in its predictions.

We find that the risk of living long and facing high medical expenses goes a long way toward explaining the elderly’s saving decisions. Specifically, these risks can explain why the elderly, and especially the income-rich elderly, run down their assets so slowly. At the other extreme, the presence of Social Security and government-provided aid programmes can explain the low saving of the elderly poor.

Life expectancy and lifespan uncertainty

Lifespans vary greatly in both predictable and unpredictable ways. Using mortality rates estimated from the AHEAD, we find that rich people, women, and healthy people live much longer than their poor, male, and sick counterparts. Two extremes illustrate this point; an unhealthy 70-year-old male at the 20th percentile of the permanent income distribution expects to live only 6 more years, that is, to age 76. In contrast, a healthy 70-year-old woman at the 80th percentile of the permanent income distribution expects to live 17 more years, thus making it to age 87. (See De Nardi et al., 2009, for a more detailed description.) Such significant differences in life expectancy could, all else equal, lead to significant differences in saving behaviour.

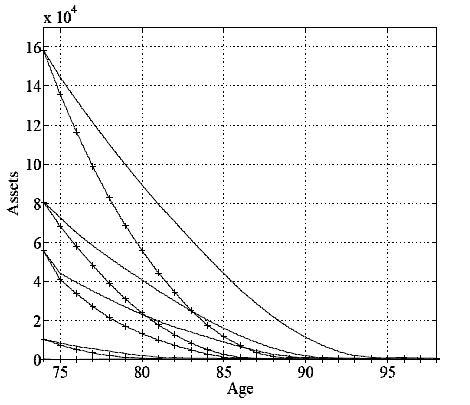

To better understand how predictable variations in life expectancy affect saving, we use our model to simulate the net worth of the AHEAD birth-year cohort whose members were aged 72 76 in 1995. Figure 1, which is taken from De Nardi et al. (2009), displays net worth profiles generated by our model. The solid lines in Figure 1 show median net worth for the baseline model. Consistent with the empirical evidence, the median net worth of the lowest permanent income quintile is close to zero and hence does not even show up on the graph. All other households draw down their net worth very slowly, with those in the highest permanent income group starting off at $160,000 in median net worth at age 74, and retaining over $100,000 until well over age 90. This, too, is consistent with the empirical evidence.

Figure 1. Median net worth (in 1998 dollars) under varying mortality assumptions

Notes: —: baseline. – · –: everyone in bad health. – –: everyone male and in bad health. –+—+–: everyone low permanent income, male, and in bad health.

The other lines in Figure 1 reflect increasingly pessimistic assumptions about how long people expect to live. The dashed-dot line adjusts each individual’s survival probabilities to those of someone who is always in bad health and has no chance of going back to good health. This reduces life expectancy at age 70 by two to four years, depending on gender and permanent income. The dashed line assumes that, besides being always sick, everyone has the life expectancy of a male, which, all else equal, is five to six years shorter than that of a female. Finally, the crossed line adds the effect of being at the lowest possible permanent income level. Under this worst-case scenario, every 70 year old expects to live five more years.

Each incremental reduction in expected lifespan generates a noticeable drop in net worth, with the high permanent income households experiencing the largest drops (in absolute terms). For people age 90 and older who are in the highest permanent income quintile, being always sick reduces median assets by around $15,000 dollars. Being male as well as sick causes assets to drop another $15,000 dollars, and being poor as well as male and sick causes assets to drop another $20,000 dollars. In short, predictable differences in life expectancy related to health, gender, and permanent income are important to understanding savings patterns across these groups, and the effect of each factor is of a similar order of magnitude.

In addition to systematic differences, individuals face significant uncertainty over their lifespans. For example, a healthy 70-year-old woman at the 80th percentile of the permanent income distribution, who expects to live 17 years, faces a 14% chance of living 25 years, to age 95. Even an unhealthy man at the 20th percentile faces an 8% chance of living to age 85, more than twice his expected lifespan of 6 years. The risk of living far past one’s expected lifespan is large and, under incomplete annuitisation, a potentially important reason why so many elderly people run down their assets so slowly.

Our previous work also quantifies the effects of lifespan uncertainty. Recall that the crossed (bottom) line in Figure 1 displays the saving of elderly people who have an expected lifespan of 5 years but face the risk of living much longer. There are no bequest motives in our model. Hence, if the same elderly people were to live five years exactly, and then die, they would deplete all of their wealth by age 75. Comparing a line of zeros from age 76 on to the crossed line in Figure 1 reveals that having uncertain lifespansgenerates large increases in saving. For 80-year-olds at the top permanent income quintile, lifespan uncertainty increases median net worth by $100,000. This comparison shows that at the levels of annuitisation provided by Social Security and private pension, the risk of outliving one’s expected lifespan is an important driver of asset holdings in old age.

Medical expenses

In De Nardi et al. (2006), we show that out-of-pocket medical expenses – which include hospital, nursing home, and doctor visits, as well as drugs and insurance premia – rise rapidly with age, especially for those with high income. For example, we find that the average annual medical expenses of a healthy woman at the 80th percentile of the permanent income distribution rise from $1,000 at age 70 to $26,000 at age 100. This feature of the data proves crucial to explaining the asset decumulation of the elderly. Medical expenses that rise with age provide elderly households with a strong incentive to save, and medical expenses that rise with permanent income encourage the rich to be especially frugal.

The importance of medical expenses can be seen in Figure 2, also from De Nardi et al. (2009), which shows the simulated asset profiles that arise when there is lifespan uncertainty but no medical costs. The solid lines in Figure 2 are asset profiles for the baseline life expectancy case. Compared to the model in Figure 1, the model with no medical costs implies a much faster rate of asset decumulation. Not surprisingly, this change is most pronounced for people in the top permanent income quintile, who otherwise would have faced the most dramatic increase in medical expenses.

Figure 2. Median net worth (in 1998 dollars) under various mortality assumptions absent medical expenses

Notes: —: baseline. –+—+–: everyone low permanent income, male, and in bad health.

In summary, our work suggests that a significant part of the elderly’s saving behaviour can be explained by health-related factors; – predictable and unpredictable variations in lifespans or out-of-pocket medical expenses.

References

Karen E. Dynan, Jonathan Skinner, and Stephen P. Zeldes. Do the Rich Save More? Journal of Political Economy, 112(2):397–444, 2004.

De Nardi, Mariacristina, Eric French, and John B. Jones, “Differential Mortality, Uncertain Medical Expenses, and the Saving of Elderly Singles,” 2006. Working Paper 12554, National Bureau of Economic Research.

De Nardi, Mariacristina, Eric French, and John B. Jones, “Life Expectancy and Old Age Savings,” 2009. Working Paper 14653, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gan, Li, Guan Gong, Michael Hurd, and Daniel McFadden, “Subjective Mortality Risk and Bequests,” 2004. Working Paper 10789, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hubbard, R. Glenn, Jonathan Skinner, and Stephen P. Zeldes, “The Importance of Precautionary Motives in Explaining Individual and Aggregate Saving,” 1994. Carnegie Rochester Series on Public Policy, pp. 59-125.

Kotlikoff, Laurence J., “Health Expenditures and Precautionary Savings.” 1998. In Laurence J. Kotlikoff, editor, What Determines Saving? Cambridge, MIT Press.

Palumbo, Michael G., “Uncertain Medical Expenses and Precautionary Saving Near the End of the Life Cycle,” 1999. Review of Economic Studies, 66, pp. 395-421.

Scholz, John Karl, Ananth Seshadri, and Surachai Khitatrakun, “Are Americans Saving Optimally for Retirement?” Journal of Political Economy 114(4), pp. 607-643.