Amid the recent Global Crisis and the persistence of global imbalances, the issue of central bank cooperation has returned to the forefront of debate (Obstfled et al. 2009, Blanchard et al. 2013, Papadia 2013, Taylor 2013, Frankel 2015, Siklos 2017). Swap networks following the crisis showed that central banks are capable of efficiently cooperating through financial transactions when needed. While we do not know of historical examples of full macroeconomic policy coordination (besides monetary unions), central banks have frequently implemented financial cooperation in order to mitigate the effects of financial crises or to maintain the stability of fixed exchange rates. But what makes such cooperation effective? What makes it fail? One should wonder if the most important threat to financial cooperation is freeriding from member central banks or, on the contrary, if financial cooperation is limited by the absence of domestic macroeconomic adjustment that would be necessary to maintain international financial and exchange rate stability.

With these questions in mind, we look at one of the most ambitious cases of central bank cooperation in history, the Gold Pool, which operated from 1961 to 1968 during the Bretton Woods international monetary system. The eight most important central banks created the Gold Pool to coordinate sales and purchases on the international gold market (located in London). The final goal of this cooperation was to maintain the gold parity of the dollar and thus the stability of the Bretton Woods international monetary system. The dollar was the main reserve currency and the only one to be pegged to gold after WWII. Members of the Pool shared profits and losses and met regularly to pilot the scheme. The demise of the Gold Pool in March 1968 led to a two-tier system (disconnection between the official and the market dollar price of gold), which technically implied the end of the Bretton Wood system (Bordo 1993).

Did the Gold Pool fail because of freeriding?

So why did the Gold Pool fail? Was it because of the freeriding of some of its members? Was France responsible for the death of the Pool – as suggested by Meltzer (1991) and others – by converting dollars into gold at the US gold window? In a recent paper, we show that it was not anti-cooperative strategies of Gold Pool members that precipitated the fall of the gold syndicate, but rather contagion from the sterling crisis to the credibility of the gold-dollar peg, in the context of inflationary US policies (Bordo et al. 2017). US domestic policies were deemed too inflationary to be credible (Bordo and Eichengreen 2013), while sterling was seen as the ‘first line of defense for the dollar’. The UK had a persisting balance of payments deficit in the 1960s, which led to a series of crises despite international rescue packages. When sterling was eventually devalued in November 1967, pressure on the dollar mounted as investors believed that it could be next in line. This occurred despite central bank cooperation.

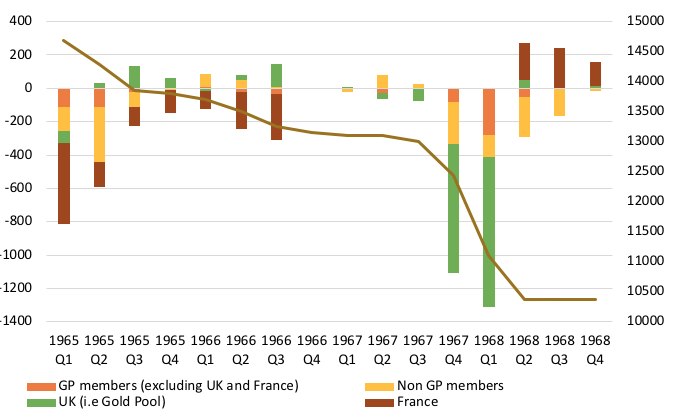

To make our argument, we use previously unreleased data on the identity of buyers at the US gold window. In order to maintain the credibility of the gold-dollar peg, members of the Pool were asked not to buy gold on the market or at the US gold window. A rapid decline in US official gold reserves would have increased expectations of a devaluation of the dollar relative to gold. In 1965, France (a member of the Pool) started exhibiting anti-cooperative behaviour by converting large amounts of dollars into gold in order to increase political pressure on the US. However, as can be seen in Figure 1, the French had long stopped converting gold at the US gold window when the Gold Pool began to come under unbearable pressure in late 1967. Moreover, narrative and quantitative evidence shows that the London gold market remained almost unaffected by the French policy (Bordo et al. 2017). The figure shows that the demand for gold in the last quarter of 1967 and first of 1968 was mainly coming from Gold Pool sales to defend the price on the London gold market. At that time, other central banks (including the Bank of France) refrained from putting pressure on US gold reserves. Freeriding was not an issue in late 1967. On the contrary, US gold reserves fell drastically because central bank cooperation worked fully through the Gold Pool to stabilise the dollar price of gold.

Figure 1 US gold window: Withdrawals from foreign central banks

Contagion between reserve currencies

The reason why the Gold Pool had to intervene so much in November 1967 was that the devaluation of sterling on 18 November had spurred speculation against the dollar on the London gold market. One might guess that the crisis and devaluation of sterling (the second reserve currency) would have increased demand for dollars (the first reserve currency). What happened was the contrary. Instead of competition, there was contagion between these two reserve currencies.

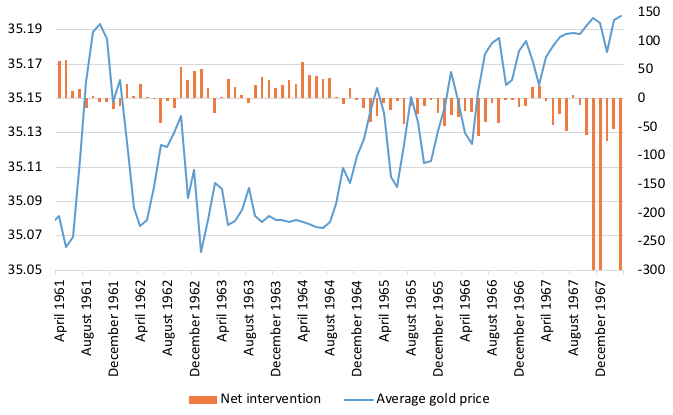

Figure 2 Gold price and Gold Pool interventions

In our paper, we show that there had been contagion between sterling and the dollar since late 1964, but that the magnitude of the effect of the sterling devaluation on the dollar price of gold in London exceeded what could have been anticipated.

After months of large interventions and political negotiations following the November sterling devaluation, the Gold Pool was terminated in March 1968. Losses were too high for members and the US was reluctant to implement policies to defend the credibility of the gold-dollar parity.

Rules-based cooperation?

Is central bank cooperation a long-term option? And can we imagine the future of central banking as an integrated network of financial coordination? The experience of the Gold Pool provides a challenge to optimists. The Gold Pool failed not because members were freeriding and trying to avoid financial losses, but simply because it delayed macroeconomic adjustments that the UK and the US were unwilling to accept, either through devaluation or inflation stabilisation. When central bank cooperation is mostly technical and takes the form of financial transactions, as it is in the case of the swap network or the Gold Pool, and it does not involve rule-based policies to prevent imbalances and adjustment problems, it is unlikely to be enough to absorb large financial and exchange rate shocks and survive in the long run (Bordo and Schenk 2017).

References

Blanchard, O, J D Ostry, and A R Ghosh (2013), “Overcoming the obstacles to international macro policy coordination is hard”, VoxEU.org, 20 December.

Bordo, M D (1993), “The Bretton Woods International Monetary System: A Historical Overview”, in M D Bordo and B Eichengreen (eds.), A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods System: Lessons for International Monetary Reform, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 3–109.

Bordo, M D, and B Eichengreen (2013), “Bretton Woods and the Great Inflation”, chapter 9 in M D Bordo and A Orphanides (eds.), The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central Banking, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bordo, M D, E Monnet, and A Naef (2017), “The Gold Pool (1961-1968) and the Fall of Bretton Woods Lessons for Central Bank Cooperation”, NBER Working Paper 24016.

Bordo, M D, and C Schenk (2017), “Monetary policy cooperation and coordination: an historical perspective on the importance of rules” in M D Bordo and J B Taylor (eds.), Rules for International Monetary Stability: Past, Present, And Future, Hoover Institution Press: Stanford, CA, 205-261.

Frankel, J (2015), “International macroeconomic policy coordination”, VoxEU.org, 9 December.

Meltzer, A H (1991), “US Policy in the Bretton Woods Era - Review - St Louis Fed”, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 73 (May/June), 54–83.

Obstfeld, M, J C Shambaugh, and A M Taylor (2009), “Financial Instability, Reserves, and Central Bank Swap Lines in the Panic of 2008”, American Economic Review 99 (2), 480–86.

Papadia, F (2013), "Central bank cooperation during the great recession”, Policy Contributions 782, Bruegel.

Siklos, P (2017), Central Banks into the Breach: From Triumph to Crisis and the Road Ahead, Oxford University Press.

Taylor, J B (2013), “International Monetary Policy Coordination: Past, Present and Future”, BIS Working Paper 437.