The coronavirus pandemic has affected life and wellbeing in a number of ways. Infection can have an immediate impact on health, and infection rates have been found to be higher in more unequal areas (Brown and Ravaillon 2020). Moreover, the impact of the economic crisis has been unequally distributed, with women, the young, and those with lower levels of education bearing the brunt of the downturn in terms of job and earnings losses (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020a, 2020b). But the pandemic has also been found to have an indirect impact on health. Social isolation has led to a deterioration of mental health, in particular among women (e.g. Etheridge and Spantig 2020).

In order to understand the role that public policy plays in mental health, in a new paper (Adams-Prassl et al. 2021) we study how the imposition of a lockdown affects someone’s psychological state. More specifically, we look at the mental condition of a person who lives in a state in the US that imposed stay-at-home orders compared to someone living in a state with no such restrictions. The fact that the decision of imposing a lockdown lies in the hands of state governors allows us to make this comparison in the US.

We use three waves of geographically representative survey data collected in the US in March, April, and May of 2020, with a total of 12,010 respondents. While at the time of our first survey only 14 states had stay-at-home orders in place, this number rose to 40 by the time we ran our April survey. By end of May 2020, 24 states had eased their stay-at-home orders. These changes within and across states in the imposition of stay-at-home orders allow us to study the effect of these measures on mental health.

To measure mental health, we use the World Health Organization’s five-question module. The five questions capture feelings and sentiments of current state of mind, and the index performs well as a tool to screen individuals who experience symptoms of, or are at risk of, depression and anxiety (e.g. Krieger et al. 2014, Topp et al. 2015).

As is common in the literature, we create a composite measure of the five responses, which is standardised to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one within each survey wave. Absent pandemics and lockdowns, women already tend to score lower, i.e. on average they have worse mental health than men (Astbury 2001, Stevenson and Wolfers 2009), as we also find in our data for March.

Our first finding is that by mid-April, a large negative impact on mental health of 0.08 standard deviations was evident in states that had stay-at-home orders in place. Crucially, no significant differences in mental health scores in March are found when comparing individuals living in states where no lockdown measures would be introduced and those where they would be, which rules out systematic differences in mental health scores before the pandemic.

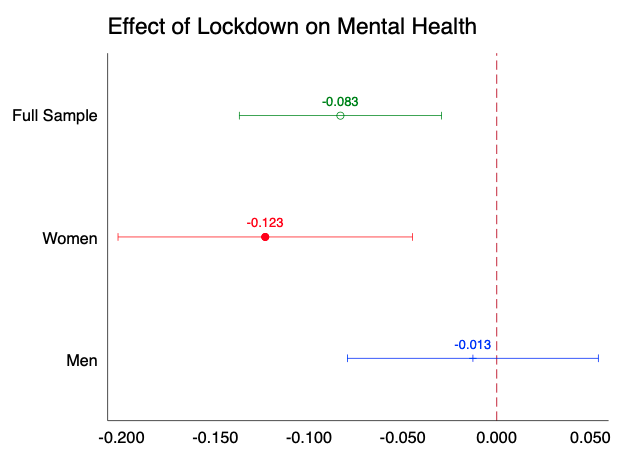

Second, the negative impact of state-wide stay-at-home measures on mental health was driven entirely by women, as can be seen in Figure 1. In states that had lockdown measures in place in April 2020, the gender gap in mental health increased from 0.21 standard deviations to 0.34 standard deviations – an increase of almost two-thirds of the pre-lockdown gap.

Figure 1 Regression coefficients of state-wide stay-at-home orders on mental health

Note: The graph shows coefficients associated to the lockdown binary variable, which takes value one if the state the respondent lives in had stay-at-home orders in place at the time of our April data collection, and zero otherwise. The dependent variable is the composite index of mental health. Additional controls include household income, a binary indicator for being single, age (in brackets), an indicator for having a university degree and an indicator for being female for the regression on the full sample.

At first sight, this might appear not to be a surprising finding given that women also suffered more on the job market and took on a larger share of home schooling and childcare responsibilities. But the gender gap in the mental health impact of lockdown measures does not close even when controlling for whether respondents earned less than usual, worked less than usual, lost their job, struggled paying their bills, or had to change work patterns or number of hours spent on childcare.

Also, the severity of the health crisis, in terms of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in a respondent’s county, cannot explain the widening gender gap. This suggests that the lockdown and social distancing measures that were put in place really had an effect on women’s mental health over and beyond the realised impacts of the crisis, such as other health and labour market outcomes.

These findings highlight the importance of policymakers taking mental health costs into account when designing policies to guide us through the COVID-19 crisis. The health costs of the coronavirus pandemic are likely to go well beyond the rising death toll and the number of cases. Going forward, appropriate resources should be invested in mental health services and prevention programmes, and online social connectedness should be explored when possibilities for in-person contacts are limited. Understanding which policies can help reducing the widening gender gap in mental health is of high importance.

References

Adams-Prassl, A, T Boneva, M Golin and C Rauh (2020a), “Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys”, Journal of Public Economics 189: 104245.

Adams-Prassl, A, T Boneva, M Golin and C Rauh (2020b), “The large and unequal impact of COVID-19 on workers”, VoxEU.org, 8 April.

Adams-Prassl, A, T Boneva, M Golin and C Rauh (2021), “The impact of the Coronavirus lockdown on mental health: Evidence from the US”, paper presented at 73rd Economic Policy panel, 15-16 April.

Astbury, J (2001), “Gender disparities in mental health”, Mental Health–Ministerial Round Tables 54th World Health Assembly, WHO.

Brown, C and M Ravallion (2020), “Poverty, inequality, and COVID-19 in the US”, VoxEU.org, 10 August.

Etheridge, B and L Spantig (2020), “The gender gap in mental well-being during the Covid-19 outbreak: Evidence from the UK “, ISER Working Paper No. 2020-08.

Krieger, T, J Zimmermann, S Huffziger, B Ubl, C Diener, C Kuehner and M Grosse Holtforth (2014), “Measuring depression with a well-being index: Further evidence for the validity of the WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) as a measure of the severity of depression”, Journal of Affective Disorders 156: 240–244.

Stevenson, B and J Wolfers (2009), “The paradox of declining female happiness”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 1(2): 190-225.

Topp, C W, S D Østergaard, S Søndergaard and P Bech (2015), “The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature”, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 84(3): 167-76.