The common view holds that managing academics is like herding cats – difficult and ultimately pointless. But this view of management contrasts with growing evidence that good management practices are like a good technology – they increase productivity (Bloom and Van Reenen 2010). Further, this finding holds for organisations in the public sector as well as in the private sector, and in many different countries across the world (Bloom et al. 2012).

For universities, raising their performance is imperative. In many countries, the public-sector funding base is shrinking, and universities face an increasingly competitive national – and international – environment for students and funds. This is particularly the case in the UK, where universities have always competed for students and research funding, and recent changes have made this competition sharper. In addition, higher education is a strategically important sector, and there is evidence that investments in research-type education should pay off in areas that are close to the world technological frontier (Aghion et al. 2010, Acemoglu 2006).

Recent research

Our recent work examines the commonly held view that management of academics is pointless (McCormack et al. 2014).

- Does management in universities matter?

- Are some universities better managed than others? and

- Is better management associated with better performance?

To examine these questions, we took a tried and tested measure of management quality developed by Bloom and Van Reenen (2007). This measure is a survey tool which has been applied to over 10,000 organisations in manufacturing, hospitals, schools, and even social care organisations (e.g. Bloom and Van Reenen 2012, Bloom et al. 2010). We used the survey tool to interview around 250 heads of departments in Business, Computer Science, Psychology, and English departments in over 100 universities in the UK in the summer of 2012. We complemented this with interviews with the heads of HR departments in universities to get a measure of the quality of management at the universities’ central administration level.

The survey covered management practices with respect to research and teaching processes, monitoring (performance measurement), targets, and use of incentives (recruitment, retention etc.). Most of the survey questions were exactly the same questions as asked in the Bloom and Van Reenen survey tool.

We first examined variation in management scores across and within universities, and then examined the relationship between the management scores and externally validated measures of research and teaching. For an overall ranking of both research and teaching we used the Complete University Guide – an independent UK guide which provides rankings that students, parents, and universities themselves use to compare the relative performance of UK universities. We also examine research performance. In the UK the government carries out a comparative assessment of university research every five years or so – we used the Research Assessment Exercise of 2008. The government also publishes a national ranking of student satisfaction (the National Student Survey scores), and we also used these as a measure of performance.

Findings

We found the following:

- First, in contrast to multi-plant manufacturing firms or even hospitals, university management is relatively decentralised.

One department within a university can have good management practices whilst another has poor ones. In addition, there are significant differences across universities in the quality of management practices.

UK universities can be split into ‘old’ (pre-1992) and ‘new’ (post-1992) universities. Old universities tend to compete nationally and internationally for students, whilst the new ones often have a more local market. Each of the two groups can be further split in two, reflecting the (relative) volume of research that takes place in each. This gives four types: the most research-intensive old universities – known as the Russell group – who receive around 75% of all research income in the whole UK university sector; other old universities; the former polytechnics; and other new universities – which do very little research and recruit locally.

- We found that the management scores of the Russell group were the highest, followed by the other old universities, the former polytechnics, and the other new universities.

Moreover, while there are differences in resources across the types of universities, these differences do not explain the results.

- The main driver of differences in the overall management score is management differences in the areas of recruitment, retention, and promotion.

Performance in terms of targets and monitoring are much more similar.

Does any of this matter?

The answer is yes.

- Our second key finding is that departments which are better managed also have better performance.

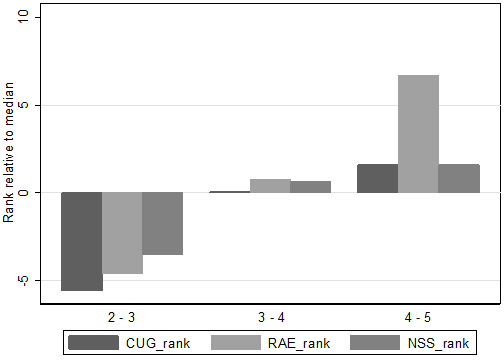

Performance is better not only in terms of research, but also in terms of student satisfaction and a wider set of metrics. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the overall ranking, research performance, and student satisfaction. The better is the management, the better are the outcomes. This holds conditional on university type, resources, and past performance. Again, the positive correlation is driven mainly by incentives which matter for both research and teaching. Monitoring and targets are much less important in explaining performance. Interestingly, the department level matters most for performance. The score of human resources departments at the same university adds nothing.

Figure 1. Management score and university performance

Note: CUG_rank refers to the department’s Combined University Guide ranking (reversed such that a higher number indicates a better ranking). RAE_rank refers to the department’s ranking in the Research Assessment Exercise (reversed such that a higher number indicates a better ranking). NSS_rank refers to the department’s ranking in the National Student Survey (reversed such that a higher number indicates a better ranking). The x-axis measures the department’s overall management score (aggregating 17 individual indicators). The overall management score is from 1 to 5; no department scored less than 2.

- Our third key finding is that it does not seem to be the case that there is one management style which is appropriate to the highly research-intensive universities and another to universities which focus more on teaching and educating local students.

Management matters in the same way at new universities as it does at old universities. In other words, good practice with respect to recruitment, retention, and promotion improves rankings for the new universities (those that were former Further Education and Higher Education colleges) just as much as it does for the old universities (Russell group).

Concluding remarks

On reflection this all makes sense. While universities deploy large bits of kit (science labs, and even in some cases run hospitals), they are nevertheless people-dominated organisations. So getting it right with respect to staff matters.

More broadly, the research fits with a couple of recent studies looking at the drivers of university performance. Aghion et al. (2010), in a cross-country study, show that universities which face greater autonomy and competition (taken together) have better performance. Goodall (2009) argues that higher-quality university leadership is associated with better performance.

Our research shows that management within the university also matters for performance. The next step is to examine how management interplays with the external environment. To this end, our aim is to compare the relationship between management and performance within universities located in different countries, where they face different levels of competition.

References

Acemoglu, D (2006), “Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth”, Journal of the European Economic Association 4(1): 37–74.

Aghion, P, M Dewatripont, C Hoxby, A Mas-Colell, and A Sapir (2010), “The governance and performance of Universities: Evidence from Europe and the US”, Economic Policy 25(61): 8–59.

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2007), “Measuring and Explaining Management Practices Across Firms and Countries”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4): 1351 –1408.

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2010), “Human resource management and productivity”, in Ashenfelter, O and D Card (eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4.

Bloom, N, C Genakos, R Sadun, and J Van Reenen (2012), “Management Practices Across Firms and Countries”, Academy of Management Perspectives 26(1): 3–21.

Bloom, N, C Propper, S Seiler, and J Van Reenen (2010), “The Impact of Competition on Management Quality: Evidence from Public Hospitals”, NBER Working Paper 16032.

Goodall, A H (2009), Socrates in the Boardroom: Why Research Universities Should be Led by Top Scholars, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McCormack, J, C Propper, and S Smith (2014), “Herding Cats? Management and University Performance”, Economic Journal 124(578): F534-64, Working paper version: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmpo/publications/papers/2013/abstract308.html