Compulsory secrecy is one of the most imposing discretionary powers that the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and other patent offices possess. Though perhaps not widely known, the USPTO has the legal authority to order firms and inventors to maintain the secrecy and suspend the examination of inventions in patent applications whose disclosure may pose risks to national security – thereby not only withholding intellectual property (IP) rights, but also effectively impounding new inventions. In contrast to compulsory licensing (Moser and Voena 2012, Watzinger et al. 2017, Watzinger et al. 2020), compulsory secrecy seeks to suppress the dissemination of innovation, and imposes significantly greater costs and constraints on the inventors concerned.1

The policy’s primary purpose is to protect domestic invention from (mis)appropriation by foreign competitors. Compulsory secrecy is invoked in ordinary times with careful discretion on tens to hundreds of patent applications a year; but in times of crisis, the prospects for its use grow, and increasing pressures of foreign technological competition over the last decade have prompted new consideration of drastically expanding its use to ‘economically important’ innovation (77 F.R. 23662).

Little is known about how compulsory secrecy affects innovation. Its broad invocation, however, is not without precedent: during WWII, the USPTO ordered over 11,000 patent applications into secrecy, covering inventions as diverse as radar, cryptography, and synthetic materials.2 The vast majority of these secrecy orders were rescinded when the war ended. The scope and scale of the policy, and its abrupt conclusion, present a rare opportunity to study the effects of compulsory secrecy on innovation and diffusion while shedding light on the value of patents and the ways that formal IP rights can interfere with ordinary inventive and commercial activity.

The WWII experiment

In a forthcoming article (Gross 2022), I use this historical experiment to study the effects of compulsory secrecy on three outcomes it implicates: incentives for innovation, diffusion, and follow-on invention.

I uncover several findings. First, firms which received secrecy orders at high rates during the war shifted their patenting away from the technology areas in which they were affected, and some temporarily stopped patenting altogether. This was particularly true for firms which were not involved in the wartime research effort. Second, the patents of firms which stayed secret for long periods were also less likely to be cited by future patents. Third, inventions ordered to remain secret were – perhaps unsurprisingly – temporarily precluded from being commercialised. Collectively, these results point to a number of the potential costs of compulsory secrecy, which distorted the direction of invention and undermined firm investments in innovation. Yet the policy appears to have worked as intended: new terms in titles of secret patents saw limited mention in patent text and the wider literature until after the war ended.

Finding secret inventions

Compulsory secrecy has its origins in WWI. Near the end of the war, Congress authorised the USPTO to order that inventions in patent applications be kept secret whenever disclosure “may endanger the successful prosecution of the war”. This authority ended with the war itself. In 1940, with WWII underway and the US bracing for entry, the law was resuscitated. Secrecy orders were indefinite in duration until rescinded. Violations were punishable by loss of patent rights, up to a $10,000 fine and two years in jail, and at worst, the loss of all existing patents and a ban on future filing.

The very idea that ‘secret’ invention can be studied is itself paradoxical: how can one observe what is explicitly secret? In this case, using the archival records of the agencies which advised USPTO on the issuance of secrecy orders, I identified 8,475 patent applications which were ordered into secrecy in WWII – around 75% of the true total of 11,200 described in administrative records – and an additional 20,000 applications evaluated for secrecy but disapproved, which I link to granted patents.

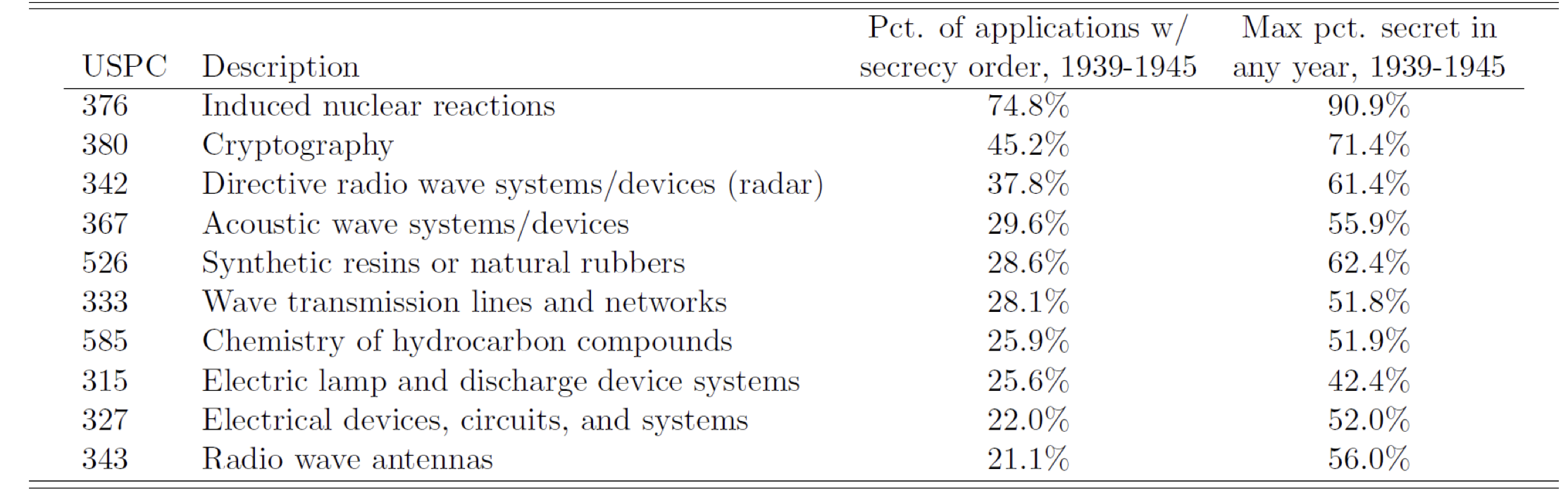

The technology areas of these secrecy orders reflected the priorities of the war effort. Table 1 lists the top ten affected patent classes, which includes technology areas like cryptography, radar and electronic communication, synthetic materials, petroleum refinement, and nuclear energy. At the height of the war, more than half of all new patent filings in these classes were sequestered.

Table 1 Top ten patent classes with applications ordered secret, 1939–1945

Notes: Table lists the ten patent classes with the highest fractions of applications from 1939–1945 placed in secrecy, in descending order, and the maximal fraction of applications in any single year ordered secret. Data for eventually granted patents only.

The consequences of compulsory secrecy

Using these data, I first compare the tendency for firms that patented in a given technology area before the war to do so again after the war, as a function of the intensity with which secrecy orders in that area were imposed during the war. Assignees more heavily affected by compulsory secrecy were more likely to stop patenting in technology areas where they were affected, an effect that persisted through 1960. A closer look at the results by subsample provides further clues: these effects are primarily driven by firms not involved in the wartime research effort (Gross and Sampat 2020) – that is, without a government customer. I then show that these firms were less likely to patent at all. Using a sample of specialty chemical catalogues from the DuPont chemical company, I also show that chemicals that first appeared in a patent with a secrecy order were less likely to be sold in catalogues until the late 1940s, indicating that secrecy orders were an impediment to the commercial sale of products they covered – one of the many reasons they might have distorted or discouraged the direction of firm patenting.

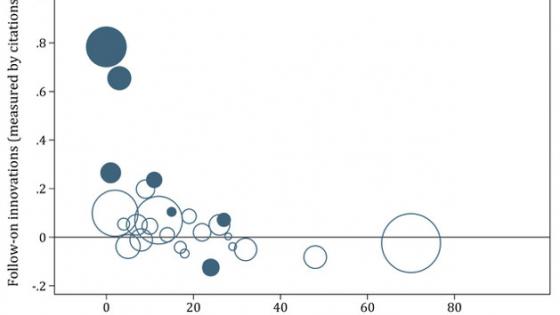

Turning attention to cumulative innovation, I show that patents with long secrecy terms were less likely to be cited by future patents than those with shorter terms, especially when restricting focus to patents filed by firms that were not wartime government R&D contractors. No such effects dogged the patents formally evaluated for secrecy but not ordered secret, which serves as a placebo. These patterns are driven by non-self-citations and hold with text-based (rather than citation-based) measures of follow-on invention, further reinforcing the result, which suggests this policy may have wiped out a full generation of follow-on invention.

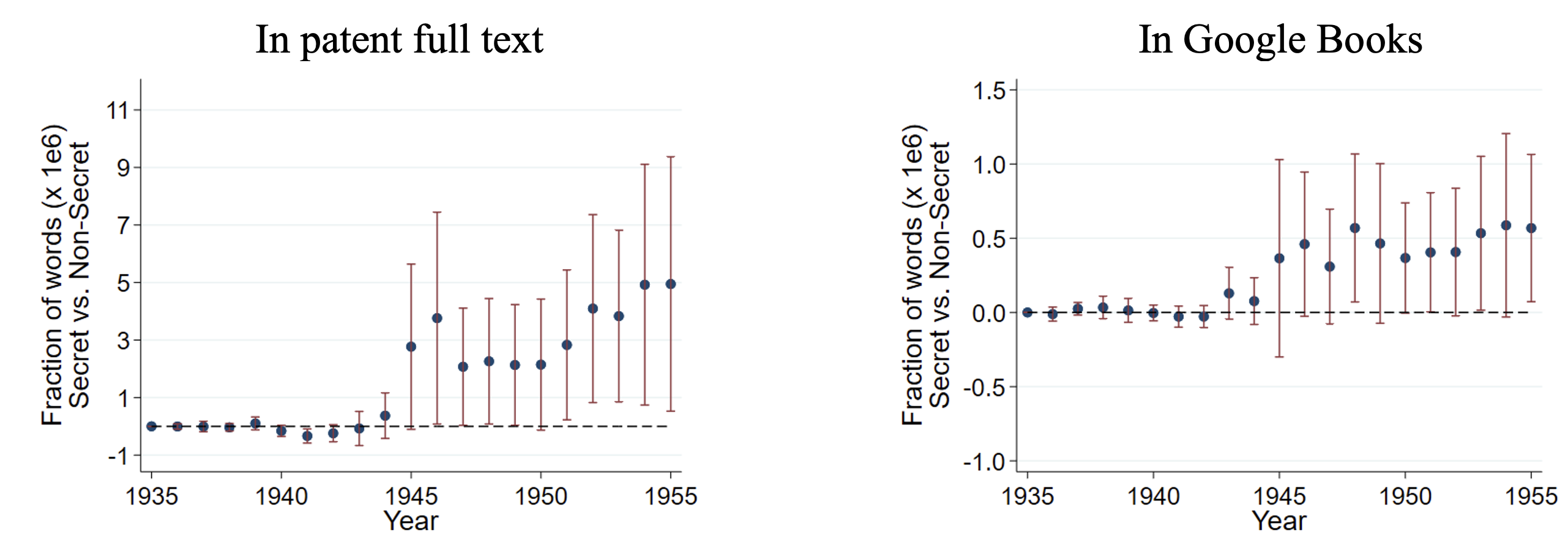

But did the policy work? To answer this question, I examine the use of new technical words from secret patents in the patent’s full text and in the broader written discourse, via the Google Books corpus of scanned works. Comparing the use of words that first appeared in secret patents to non-secret patents, by year, I find that words from secret patents – such as “radar”, “fission”, or “penicillin” – were not used at differential rates prior to 1945. But after the war, use of words from secret patents discretely and permanently jumps. As is the case throughout the paper, there are no such effects for words from patents evaluated for secrecy but not ordered secret. The sharp jump in the use of these words after secrecy orders were lifted in 1945 suggests the policy was effective at averting disclosure.

Figure 1 Annual use of new words in secret vs. non-secret patent titles

Notes: Figure shows estimated differences over time in the patent full text (left panel) Google Books corpus (right panel) frequency of words which first appeared in the title of a secret versus non-secret patent filed from 1940–1945. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Broader implications

This historical experiment presents a number of lessons for current IP research, policy, and strategy.

Basic principles of both intellectual property rights and scientific openness have long been enshrined in US law and policy, with the original Patent Act of 1790 requiring inventors to disclose their inventions in exchange for property rights. Compulsory secrecy directly defies these goals, undoing the advantages that intellectual property rights are intended to foster.

The results of this paper illustrate what can happen when these benefits are withheld, even temporarily: patenting may decline or shift towards protected subjects, and commercial impacts and follow-on invention may be stymied. Though WWII was an extraordinary time, the domestic US economy – unlike Europe’s – was still functioning. The evidence is thus suggestive of the impacts a similar revocation of IP rights and disclosure may have in other crises or even in regular times.

Not all firms are likely to be equally affected by compulsory secrecy. Some may even stand to benefit. Restricting information flows creates a dynamic trade-off: firms lose access to information about rivals that might advance its investments in innovation today, but its rivals do as well, averting competing innovation tomorrow. These restrictions might be advantageous for incumbents, who can earn rents on past R&D investments when innovation and entry are stymied. Similarly, the abrogation of formal IP rights may be good for firms that do not rely heavily on them and are able to protect their IP by other means. Consistent with this possibility, I find that large firms were less affected.

Finally, this paper speaks to the role of information in the functioning of the wider innovation system. Access to state-of-the-art scientific and technical knowledge can be a key input to technological progress (Iaria et al. 2018, Biasi and Moser 2021, Furman et al. 2021, Hegde et al. 2021). Legal scholars often argue that patent documents are not themselves an important source of information (e.g. Roin 2005). Compulsory secrecy imposes significantly broader restrictions on disclosure than preventing patent publication alone. Their effects on subsequent invention are thus suggestive of the value of unrestricted information flows in supporting cumulative innovation.

References

Biasi, B and P Moser (2021), “Effects of Copyrights on Science: Evidence from the WWII Book Republication Program”, American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 13(4): 218–260.

Furman, J, M Nagler and M Watzinger (2021), “Disclosure and Subsequent Innovation: Evidence from the Patent Depository Library Program”, American Economic Journal: Economy Policy 13(4): 239–270.

Gross, D P (2022), “The Hidden Costs of Securing Innovation: The Manifold Impacts of Compulsory Invention Secrecy”, forthcoming at Management Science.

Gross, D P and B N Sampat (2020), “Inventing the Endless Frontier: The Effects of the World War II Research Effort on Post-war Innovation”, NBER Working Paper No. 27375.

Gross, D P and B N Sampat (2022), “Crisis Innovation Policy from World War II to COVID-19”, in Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 1, University of Chicago Press.

Hegde, D, K Herkenhoff and C Zhu (2022), “Patent Publication and Innovation”, available at SSRN.

Iaria, A, C Schwarz and F Waldinger (2018), “Frontier Knowledge and Scientific Production: Evidence from the Collapse of International Science”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(2): 927-–991.

Ito, B (2021), “Impacts of the vaccine intellectual property rights waiver on global supply”, VoxEU.org, 08 August.

Moser, P and A Voena (2012), “Compulsory Licensing: Evidence from the Trading with the Enemy Act”, American Economic Review 102(1): 396–427.

Roin, B N (2005), “The Disclosure Function of the Patent System (Or Lack Thereof)”, Harvard Law Review 118: 2007–2028.

Watzinger, M, T A Fackler, M Nagler and M Schnitzer (2017), “How antitrust enforcement can spur innovation: Bell Labs and the 1956 Consent Decree”, VoxEU.org, 19 February.

Watzinger, M, T A Fackler, M Nagler and M Schnitzer (2020), “How Antitrust Enforcement Can Spur Innovation: Bell Labs and the 1956 Consent Decree”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12(4): 328–59.

Endnotes

1 For modern applications, see e.g. Ito (2021) on the COVID-19 crisis.

2 Being a technological war (Gross and Sampat 2020, 2022), concealing technology from foreign enemies was critical to the US and other countries’ WWII military strategy.