The spread of Covid-19 has caused tremendous stress to public health around the globe. As the scale of the pandemic became increasingly clear to investors in March 2020, financial markets were strongly affected – both in terms of valuations and their functioning. Economists use the concept of market liquidity to capture the ease of trading in financial markets. In this column, we study how market liquidity in European sovereign bonds evolved at the start of the pandemic, and explore the main possible drivers of this evolution: ‘dash for cash’ or ‘dash for collateral’.

We first focus on German Bunds, which serve as a benchmark safe asset for the euro area and beyond. The liquidity of risk-free assets such as Bunds is a key measure of market stress. In the US, widespread selling pressure – a ‘dash for cash’ – led to a dramatic deterioration of liquidity conditions in the Treasury market by early- to mid-March (Duffie 2020, Muzinich 2020). To answer the question of whether this deterioration was mirrored in European sovereign bond markets, we use data from the inter-dealer platform, MTS.

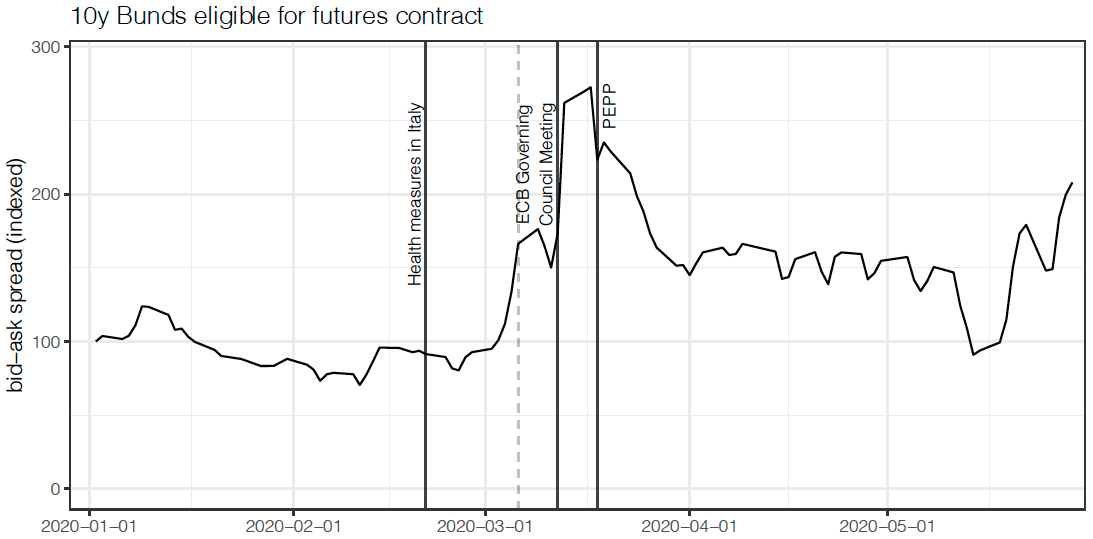

Figure 1 Average bid-ask spread of German sovereign bonds eligible for the current 10 years futures contract

Note: 3-day rolling average indexed to 100 for 2 Jan 2020.

Source: MTS, own calculations.

A standard measure of liquidity is the bid-ask spread. This measures the transaction cost dealers charge each other for trading Bunds. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the average bid-ask spread quoted for German reference bonds from January to May 2020.1 The solid vertical lines in Figure 1 indicate (1) the enforcement of health measures in Italy on 21 February 2020, (2) the meeting of the ECB governing council on 12 March 2020, and (3) the announcement of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) on 18 March 2020. This programme was introduced to “counter the serious risks to the monetary policy transmission mechanism and the outlook for the euro area posed by the outbreak and escalating diffusion of the coronavirus, COVID-19” (ECB 2020). The figure shows that the bid-ask spread began to rise at the beginning of March. Shortly after the ECB Governing Council meeting, it reached more than double its pre-pandemic level. Around the announcement of the PEPP, the bid-ask spread started to fall again but remained at approximately 150% of its pre-pandemic levels thereafter. The increase in transaction cost is not limited to the inter-dealer segment. As we show in a related research paper (de Roure et al. 2020), transaction costs in the inter-dealer (D2D) and the dealer-to-customer (D2C) segments of the Bund market are closely related. Indeed, a similar picture of increased transaction costs emerges from D2C trades reported on Bloomberg (Nguyen 2021).

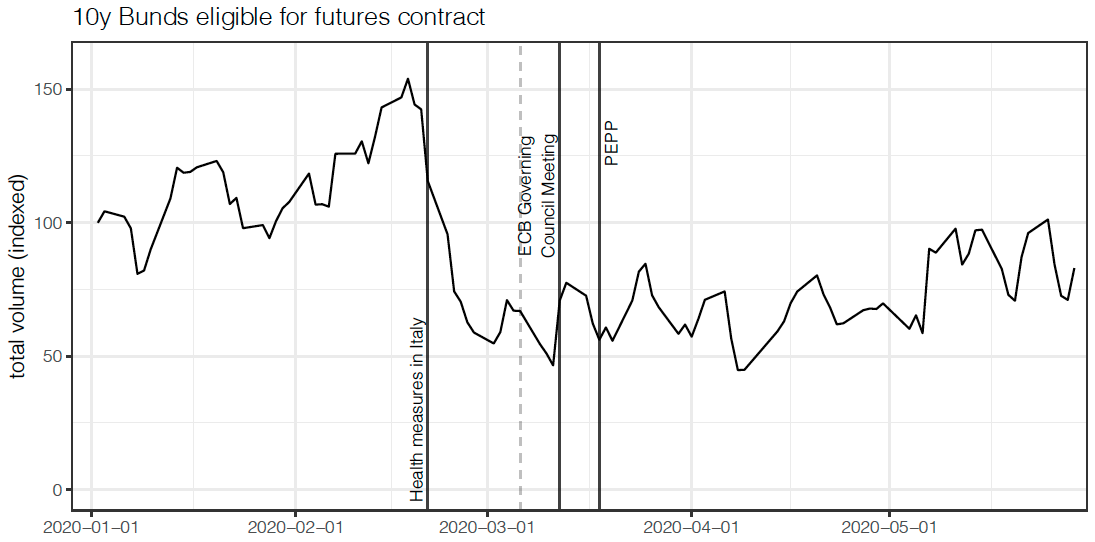

Figure 2 Average volume available for trading in the MTS order book across all levels, for German sovereign bonds eligible for the current 10 years futures contract

Note: 3-day rolling average indexed to 100 for 2 Jan 2020.

Source: MTS, own calculations.

Another important indicator of liquidity is the market depth. This is measured as the average overall volume that is quoted via limit orders in the MTS order book. This measure indicates dealers’ willingness to provide liquidity to each other (Schneider et al. 2018). As Figure 2 shows, the overall market depth plunged with the introduction of health measures in Italy (21 February 2020), several weeks before a reaction in the bid-ask spread became visible. Only about half of the pre-pandemic level of liquidity was available after February 2020, and there was no discernible improvement after the ECB governing council meeting or the subsequent PEPP announcement. Only in May did market depth improved somewhat. Interestingly the US Treasury market depth retreated well before the bid-ask spread increased (Duffie 2020).

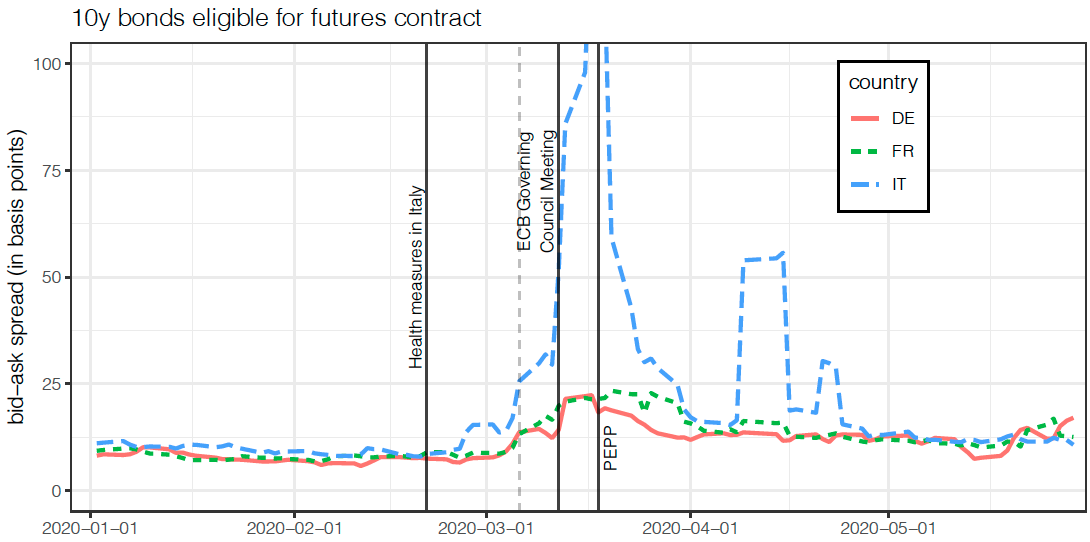

Figure 3 Liquidity measures across European countries

Source: MTS, own calculations.

Looking beyond German Bunds, we observe similar patterns in the markets for French and Italian sovereign bonds – the two largest sovereign debt markets in Europe by amount issued.2 Bid-ask spreads (shown in the upper panel of Figure 3) were at similar levels at the beginning of the year but started to increase in Italy in late-February and in early-March in France. In particular, bid-ask spreads on Italian bonds then spiked sharply in mid-March 2020, reaching very high levels of more than 100 basis points. Bid-ask spreads retreated to approximately 150% of their pre-pandemic levels for all countries by the end of April. The overall volume available for trade (depicted in the lower panel of Figure 3) moved in lockstep across countries, and also started to fall shortly after the introduction of health measures in Italy. The drop in overall bond volume available for sale was largest in France.

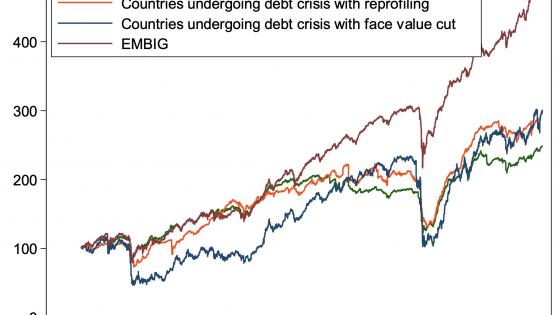

Figure 4 RepoFunds rate

Source: Bloomberg.

In the US Treasury market, the sharp increase in trading frictions was accompanied by a spike in sales of Treasuries in March 2020 (Duffie 2020, Financial Stability Board 2020, Vissing-Jorgensen 2020). Similar effects were also observed in the UK gilt market (Hüser et al. 2021). These sales of safe assets were attributed to a ‘dash for cash’ by non-financial corporates, banks, and other intermediaries as the pandemic unfolded (Quarles 2020, Vissing-Jorgensen 2020).

Was the deterioration of European sovereign debt market liquidity that we document above equally associated with widespread selling pressures? To answer this question, we look at rates on repurchase agreements which can be interpreted as a measure of the scarcity of bonds as collateral. Figure 4 shows that in contrast to the US and UK experience, there was a sharp decline in the ‘RepoFunds rate’ for France and Germany at the end of March. That is, borrowers in the repo market were willing to pay a ‘specialness premium’ in order to receive French or German sovereign bonds as collateral (Billio et al. 2020). This suggests a ‘dash for collateral’ – an increased demand for Bunds and French sovereign debt – rather than a ‘dash for cash’. While this effect cannot be seen in Italian sovereign debt, the ‘repo spreads’ do not indicate strong selling pressures at the onset of the pandemic.

To conclude, we document that European sovereign debt markets experienced a strong deterioration of market liquidity at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in February and March 2020. These patterns were similar across the largest three euro area economies, and resemble those in the US Treasury market. However, a dash-for-cash effect with an increased demand for cash or short-term Treasury Bills (as observed in the US) did not manifest itself in Europe for the French and the German sovereign bonds. Instead, the increased economic uncertainty led to an increased demand for euro-denominated safe assets (i.e. a ‘flight to safety’ or a ‘dash for collateral’).

Authors’ note: This column represents the views of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

References

Billio, M, M Costola, F Mazzari and L Pelizzon (2020), “The European Repo Market, ECB Intervention and the COVID-19 Crisis”, A New World Post COVID-19 58.

de Roure, C, E Moench, L Pelizzon and M Schneider (2020), “OTC Discount”, SAFE Working Paper 298.

Duffie, D (2020), “Still the World’s Safe Haven? - Redesigning the US Treasury Market After the COVID-19 Crisis”, Hutchins Center Working Paper 62.

ECB (2020), “ECB announces €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)”, Press Release, 18 March.

Financial Stability Board (2020), “Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil”.

Hüser, A-C, C Lepore and L Veraart (2021), “How do secured funding markets behave under stress? Evidence from the gilt repo market”, Bank of England, Staff Working Paper 910.

Muzinich, J (2020), “Remarks at the 2020 U.S. Treasury Market Conference”.

Nguyen, P A (2021), “Exploring market liquidity of sovereign bonds using MiFID II data”. Master thesis, Goethe University Frankfurt.

Quarles, R K (2020), “What happened? What have we learned from it? Lessons from COVID-19 stress on the financial system”, speech from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 15 October.

Schneider M, F Lillo and L Pelizzon (2018), “Modelling illiquidity spillovers with Hawkes processes: an application to the sovereign bond market”, Quantitative Finance 18(2): 283-293

Vissing-Jorgensen, A (2020), “Bond markets in Spring 2020 and the response of the Federal Reserve”, Working Paper.

Endnotes

1 As reference bonds we refer to those bonds that are eligible for the current 10-year futures contract. The change of contract, and thus part of the reference bond universe, on the pre-defined date of 6 March 2020, indicated by vertical dashed lines in the figures, does not influence our results.

2 See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_17_40/default/table?lang=en