There has been a shift towards decentralisation in a majority of OECD countries over the past few decades. Between 1995 and 2016, the importance of subnational governments – measured as their spending share of GDP and share of total public spending – in two-thirds of OECD countries has increased. Today, regions and cities account for 40.4% of public spending and 56.9% of public investment in the OECD (OECD 2019). They play an increasing role in key policy areas, such as transport, energy, broadband, education, health, housing, water, and sanitation. Decentralisation can also be a crucial tool to build citizens’ trust in institutions and improve wellbeing. It provides constituents with the right incentives to more actively screen the performance of local decision-makers and thus affect the quality of local public services.

Yet, the capacity of citizens to reward high-performing local politicians or vote out those who are under-performing – and thus affect the quality of local public goods – largely depends on local institutional design. For example, accountability may be stronger if citizens elect mayors directly rather than leaving their appointment to city parliaments. Directly elected mayors may feel more accountable towards their electorates than appointed mayors, which in turn can impact the provision of public goods in their constituencies (Hessami 2018). Building on this logic, reforms introducing directly elected mayors have become more common over the past few decades. Italy institutionalised the direct election of mayors throughout the country in 1993; in the UK, the Greater London Authority had its first directly elected mayor in 2000; Croatia and Ireland introduced direct mayoral elections countrywide in 2009 and 2011, respectively.

The direct election of mayors improves policing and increases safety

The question is whether more accountability affects the quality of local public services in addition to the behaviour of mayors. In a recent paper (Colombo and Tojerow 2020), we test whether a reform introducing the direct election of mayors in Belgium impacted their decisions about the provision of a local public good, namely policing. Belgium is a very decentralised country and its mayors are the head of their local police force, which has extensive responsibility for combating criminality and preserving safety. We further contribute to the policy debate around the transparency of police management, for which demand has been rising across OECD countries over the past decade, and which has recently come under scrutiny in countries like the US and France.

We exploit a 2005 reform implemented in Belgium that introduced the direct election of mayors in one of the three federal regions, Wallonia. Mayors in the other regions (Flanders and Greater Brussels) remained appointed by their respective city councils. We collected and centralised data about crime and local election performance between 2000 and 2012 and compared crime incidence in municipalities with directly elected mayors to those with appointed mayors, before and after the 2005 reform.

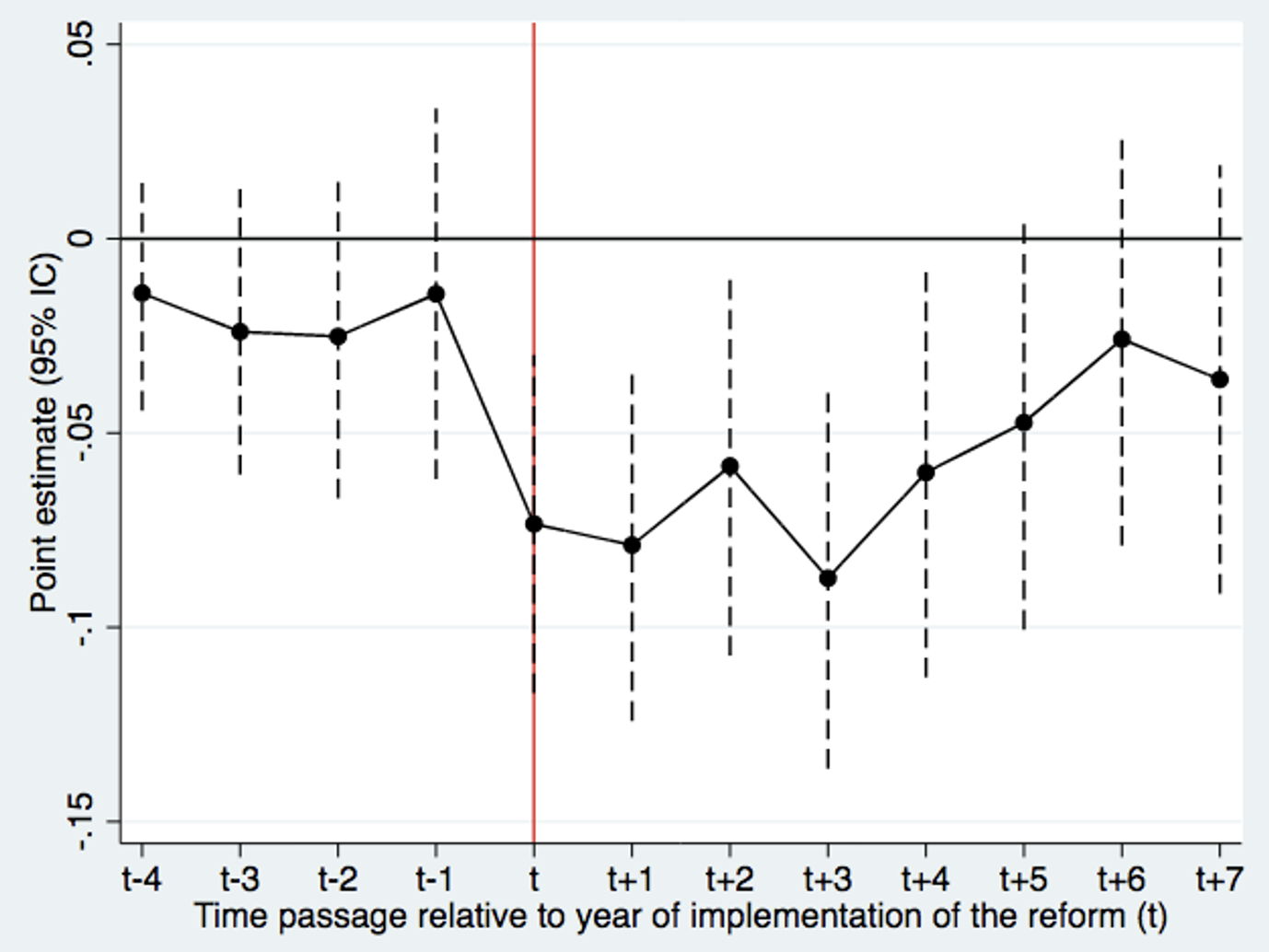

Overall, we found a statistically significant decrease in crime incidence of 4.6% in the municipalities impacted by the reform (Figure 1). The direct election of mayors seems to have a positive causal impact on the provision of safety at the local level. Looking at the impact by type of crime, we show that directly elected mayors particularly encourage policing against violence and robbery, two of the most electorally sensitive categories of crime.

Figure 1 The effects of introducing the direct election of mayors on safety, by year

Note: The graph represents the ordinary least squares estimated coefficients and the respective 5% coefficient intervals. The dependent variable (on the y axis) is the log incidence of main crime events. Values are taken from official crime statistics, as reported by the local police, from 2000 to 2012. Standard errors are clustered at the municipal level and allow for arbitrary correlation of residuals within each municipality (Colombo and Tojerow 2020).

We argue that the 2005 Wallonian reform made local elections more competitive, which increased the accountability of mayors to citizens and their effort to fight criminality. Starting from the first region-wide direct elections, in 2006, incumbent mayors who ran for re-election faced a wider pool of potential opponents, both from other parties and from the same list. In order to stand out from the crowd of candidates and gain support, their campaigns focused on issues they could control directly, such as safety (Aragonès et al. 2015). Voters were therefore able to acquire more information on a candidate’s priorities and vote for those with a clear plan to address criminality. Once elected, mayors would then monitor their police forces to uphold to electoral promises, especially in view of re-election. It is for all these reasons that the direct election of mayors created incentives for mayors to provide public goods of a better quality.

The beneficial effect of direct election on safety depends on the governance of local police

Belgium is divided into police districts that may encompass several municipalities and require several mayor-chiefs of police to coordinate law enforcement. Co-management of policing could yield advantages in terms of cost-benefits: municipalities – especially small municipalities – may not have the human and financial capacity to tackle issues like criminality that often overstep borders. Pooling forces and resources can help reach the minimum scale required for effective action.

Co-management may increase the costs of coordination and pose problems in terms of accountability (Gailmard 2009). As police districts grow, mayors might delegate the management of local police to non-elected bureaucrats in intermediary bodies, leaving citizens less able to hold their mayors accountable for local safety. Moreover, co-management creates incentives for mayors to ‘free ride’. The direct election of mayors may therefore have a small impact on policing quality and safety in municipalities belonging to large police districts.

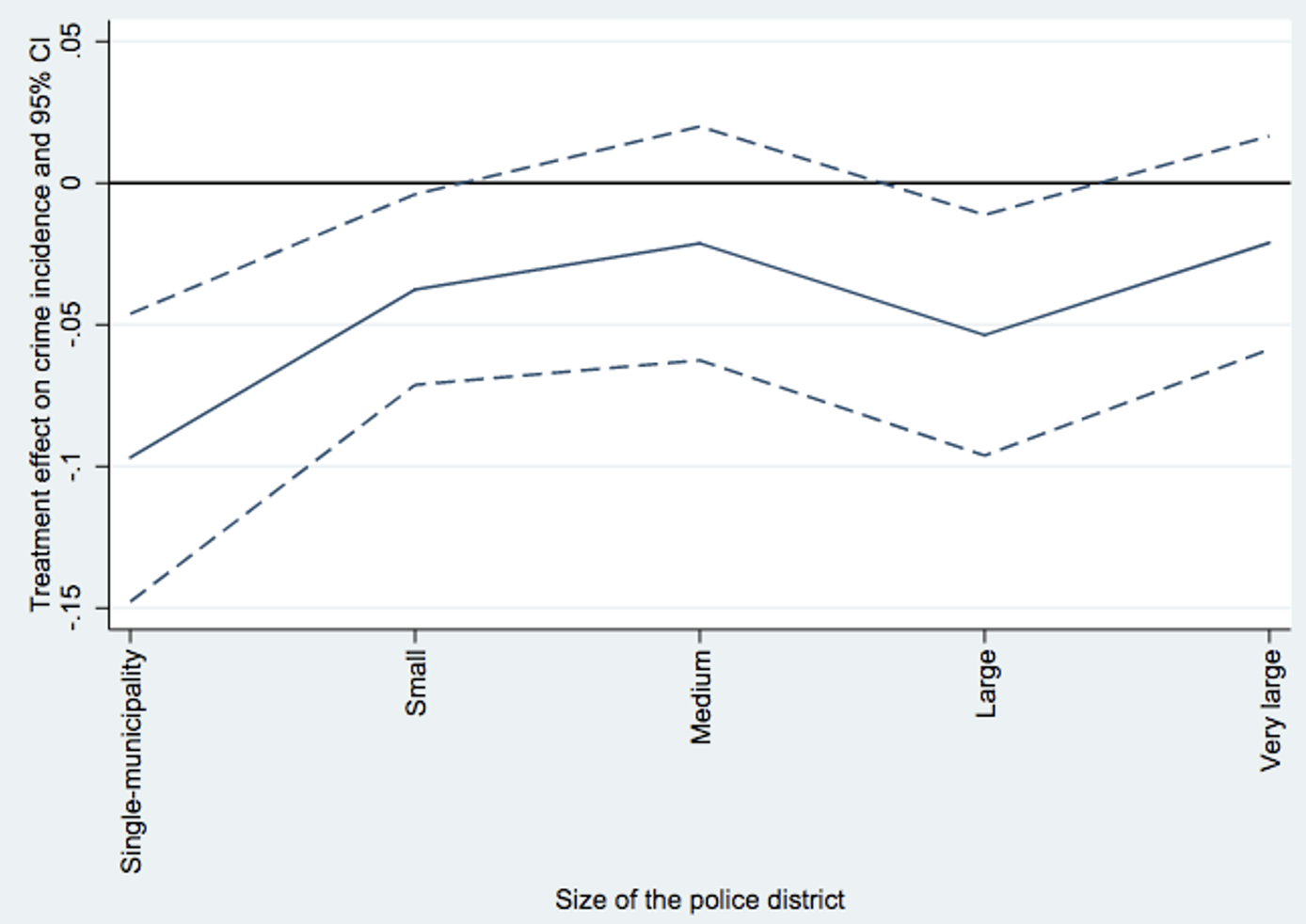

Our results validate this hypothesis and show that the beneficial impact of the direct election of mayors on safety decreases when the police district covers more than one municipality and is therefore under the supervision of several mayors (Figure 2). We also find that this decreasing effect is particularly important when the mayors of the municipalities constituting the police district belong to different political parties. This hints at a lower propensity for mayors from different political parties to cooperate. While coordination could generate economies of scale, it mainly raises costs and moral hazard issues that could lead to the underprovision of common public goods (Dixit 2002).

Figure 2 The effects of the reform on safety decreases in large police districts

Note: ‘Single-municipality’ police districts (PD) have only one municipality. ‘Small’ PDs count two to three municipalities; ‘medium’ PDs have four to five municipalities; ‘large’ PDs count six to seven municipalities; ‘very large’ PDs have more than seven and up to ten municipalities (Colombo and Tojerow 2020).

Direct election of mayors can improve the quality of local public services, depending on the governance of their provision

The introduction of direct elections of local politicians can improve the quality of public services. Following the introduction of this reform in one region of Belgium, our paper finds that electoral competition has tightened and pushed candidates to campaign on issues they could more directly control, such as safety. This change led voters to have access to more information on different candidates and to vote for those who took a clear stand on fighting criminality. The increased electoral competition also pushed mayors to monitor their police force more tightly, especially in view of re-election.

We find that the beneficial effect of direct election on safety is diluted when policing is co-managed by neighbouring municipalities. Shared provision of policing seems to make it more difficult for citizens to monitor the provision of the public good, thus offsetting the benefits of direct election. Moreover, shared mandates also increase the cost of coordination among mayors, especially in large and politically diverse police districts (Ater et al. 2014, Estache et al. 2016).

To conclude, the modality of the election of local decision makers as well as the governance of local public goods determine whether decentralisation is able to deliver. Shifting power and resources to the local level requires a carefully engineered sequence of structural reforms that takes into account pre-existing local institutions and equips local authorities with the capacity to provide quality public goods and services.

References

Aragonès, E, M Castanheira and M Giani (2015), “Electoral Competition Through Issue Selection”, American Journal of Political Science 59(1): 71–90.

Ater, I, Y Givati and O Rigbi (2014), “Organizational Structure, Police Activity and Crime”, Journal of Public Economics 11: 62–71.

Colombo, A and I Tojerow (2020), "Appointed or Elected? How Mayoral Accountability Impacts the Provision of Policing", Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) DP No. 13961.

Dixit, A (2002), “Incentives and Organizations in the Public Sector: An Interpretative Review”, Journal of Human Resources 37(4): 696–727.

Estache, A, G Garsous and R Seroa da Motta (2016), “Shared Mandates, Moral Hazard, and Political (Mis) alignment in a Decentralized Economy”, World Development 83: 98–110.

Gailmard, S (2009), “Multiple Principals and Oversight of Bureaucratic Policy-making”, Journal of Theoretical Politics 21(2): 161–186.

Hessami, Z (2018), "Accountability and incentives of appointed and elected public officials", Review of Economics and Statistics 100(1): 51–64.

OECD (2019), Making Decentralisation Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers.