Economic growth is inherently tied to the movement of labour out of agriculture into manufacturing and services: a process called structural transformation (Herrendorf et al., 2014). Naturally, economists have asked: what is the engine of structural transformation? Which are the economic forces that lead workers to step out of farms into factories and then offices?

Two broad explanations have been usually proposed.

- Unbalanced productivity growth: over time, countries become extremely good at producing agricultural goods, thus needing only a small share of the workers to feed the population (Ngai and Pissarides 2007, Duernecker et al. 2018).

- Income effects lower the relative demand for agricultural goods: as countries become richer, individuals spend a lower share of their income to buy agricultural products, leading workers to reallocate to goods and services (Kongsamut et al. 2001).

In both cases, a country-level phenomenon reduces the relative need for workers in agriculture, thus leading to labour reallocation. This is what labour economists would call a shift in the relative demand for agricultural workers.

These two arguments, however, typically focus on aggregate labour statistics and ignore another important side of the story: the human side. To generate an aggregate decline in agricultural employment, individuals must decide to change jobs, transition between sectors, and possibly migrate from rural to urban areas. Similarly, new cohorts born in rural areas must choose to search for work in the cities rather than replacing the retiring old farmers. Therefore, behind the decline in aggregate agricultural employment, there are humans actively choosing in which sector to work. Their choices will be affected not only by country-wide trends, but also by individual-specific factors, such as their preference to live or work in the rural area, the barriers they may face to change sectors, and - importantly – their skill sets.

In recent work (Porzio et al. 2021), we argue that considering this human side is crucial to understanding structural transformation. We show that younger generations with higher human capital are endowed with skills more valued outside of agriculture, which leads them to be less willing to stay on the farm. This is what labour economists would call a shift in the relative supply of agricultural workers.

We develop this argument in four steps:

- First, we show that the entering cohorts played a key role in structural transformation.

- We then argue that these cohort differences reflect, in large part, differences in human capital, which make new generations more suitable to work outside of agriculture.

- Next, we use a quantitative model to quantify the aggregate impact of supply shift.

- Finally we ask what the main driver of human capital accumulation is, and what policy conclusions can we draw?

New birth cohorts play a key role in structural transformation

Using individual-level data from 52 countries, covering more than two-thirds of the world population, we unpack the process of labour reallocation out of agriculture by following birth-cohorts of male individuals over time and studying their occupational choices.

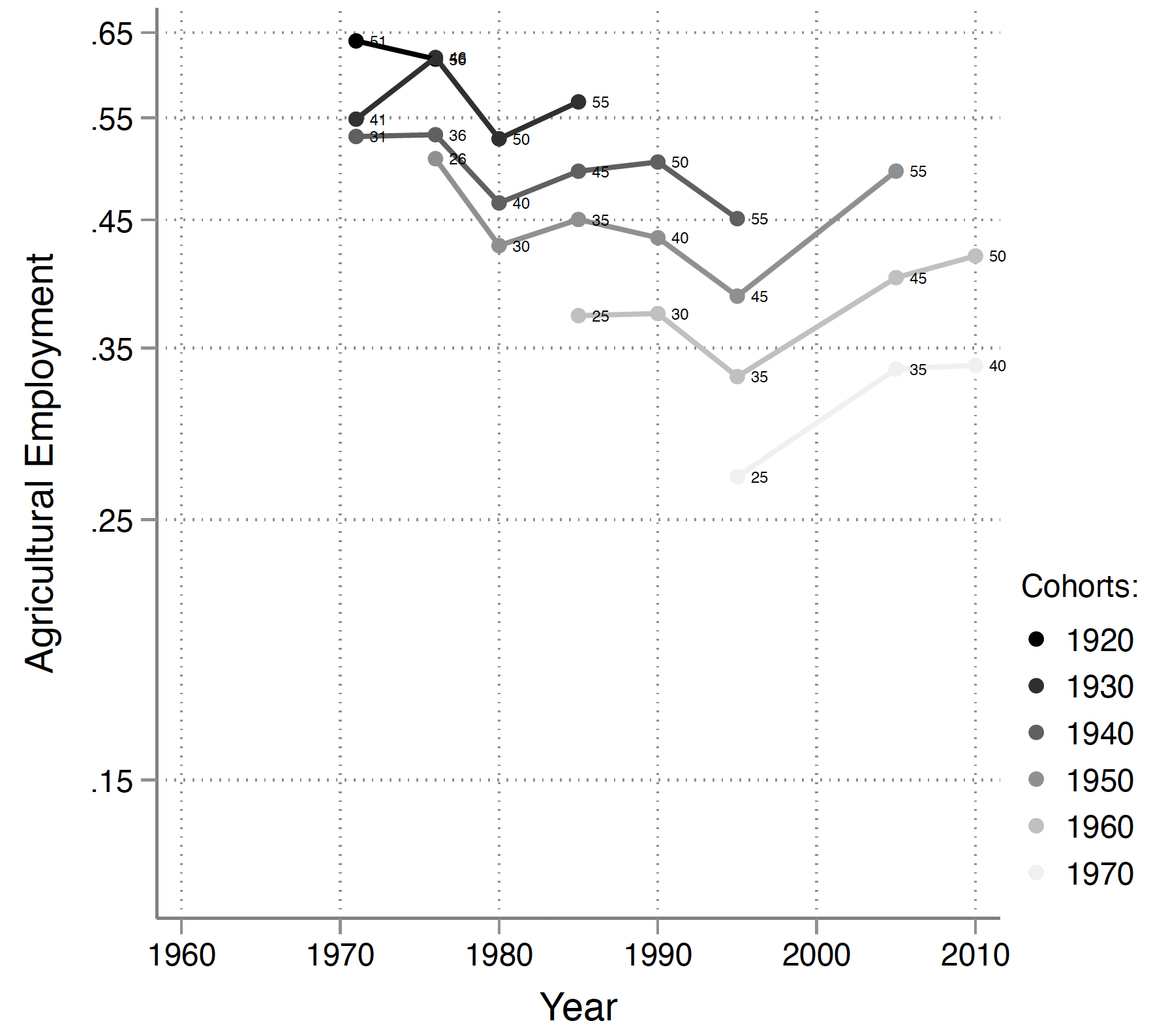

Figure 1 illustrates the empirical exercise for two countries: Brazil and Indonesia. In Panel (a), we notice that younger cohorts in Brazil tend to have a smaller share working in agriculture, yet most of the overall structural transformation is due to workers, within each birth cohort, moving out of agriculture over time. Not all countries look like Brazil. Panel (b) shows that in Indonesia, we see almost no decrease in the share of men working in agriculture within each birth cohort, while younger cohorts do have a smaller share in agriculture, as in Brazil.

Figure 1 Labour reallocation by cohort, two examples

(a) Brazil

(b) Indonesia

Notes: the figures plot agricultural employment by birth cohort in Brazil and Indonesia. The ages of all cohorts in any observed year are reported.

We conduct a similar analysis for each country in our sample. Overall, most countries look like a combination of Brazil and Indonesia, with large decreases in agricultural employment both within and between cohorts. Through a simple decomposition, we show that, on average, new birth-cohorts account for approximately half of the aggregate labour reallocation out of agriculture across all countries. This result implies that there has been a large decline in the supply of agricultural labour as the young generations are more likely to take opportunities outside of the agricultural sector.

What makes young cohorts different? Their human capital

Having established that younger birth cohorts have a comparative advantage towards non-agricultural work, our next step is to bring evidence that this is due to them having higher human capital. To do so, we hand-collect a new dataset that contains events that might have affected schooling and, more broadly, human capital accumulation of birth-cohorts while young. We then show that events that positively affected birth-cohorts when they were young led them to be relatively more likely to work outside of agriculture after several decades.

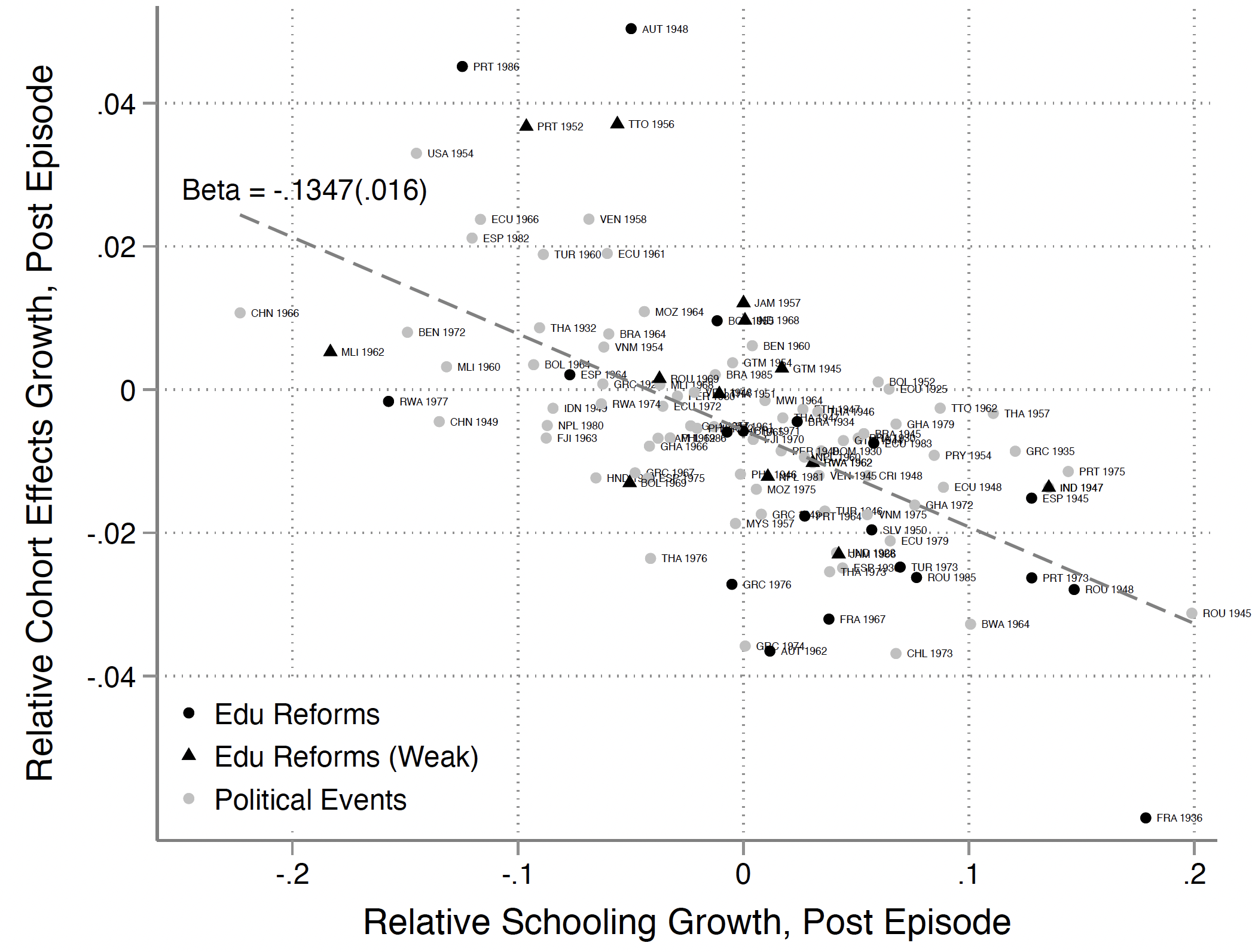

A fitting example, shown in Figure 2a, is the war for independence from Portugal fought by Mozambique between 1964 and 1975. The war disrupted the educational system, as confirmed by the stagnating educational attainment for the cohorts starting primary school in that time window. When grown up, the same cohorts were more likely to work in agriculture (as shown by higher cohort effects in the figure), relative to the trend. After independence, the Mozambique Liberation Front initiated extensive programmes for economic development, including free healthcare and education, which are reflected in the faster schooling growth and lower future agricultural employment for cohorts born after 1970.

Figure 2b shows that the example of Mozambique generalises to all countries. Cohorts that have been exposed to political events or schooling reforms that limit their investment in human capital during youth are more likely to work in agriculture during adulthood.

Figure 2 Trend breaks around education reforms and political events

(a) Example: Political events in Mozambique

(b) All episodes

Notes: figure (a) plots, for Mozambique, the cohort effects in agricultural employment and schooling for all available birth cohorts. The red vertical lines identify the oldest cohorts not yet in school at the start and end of the independence war. Figure (b) plots the changes in the growth rate of cohort effects after a reform (in black) or political event (in grey), against the corresponding changes for schooling.

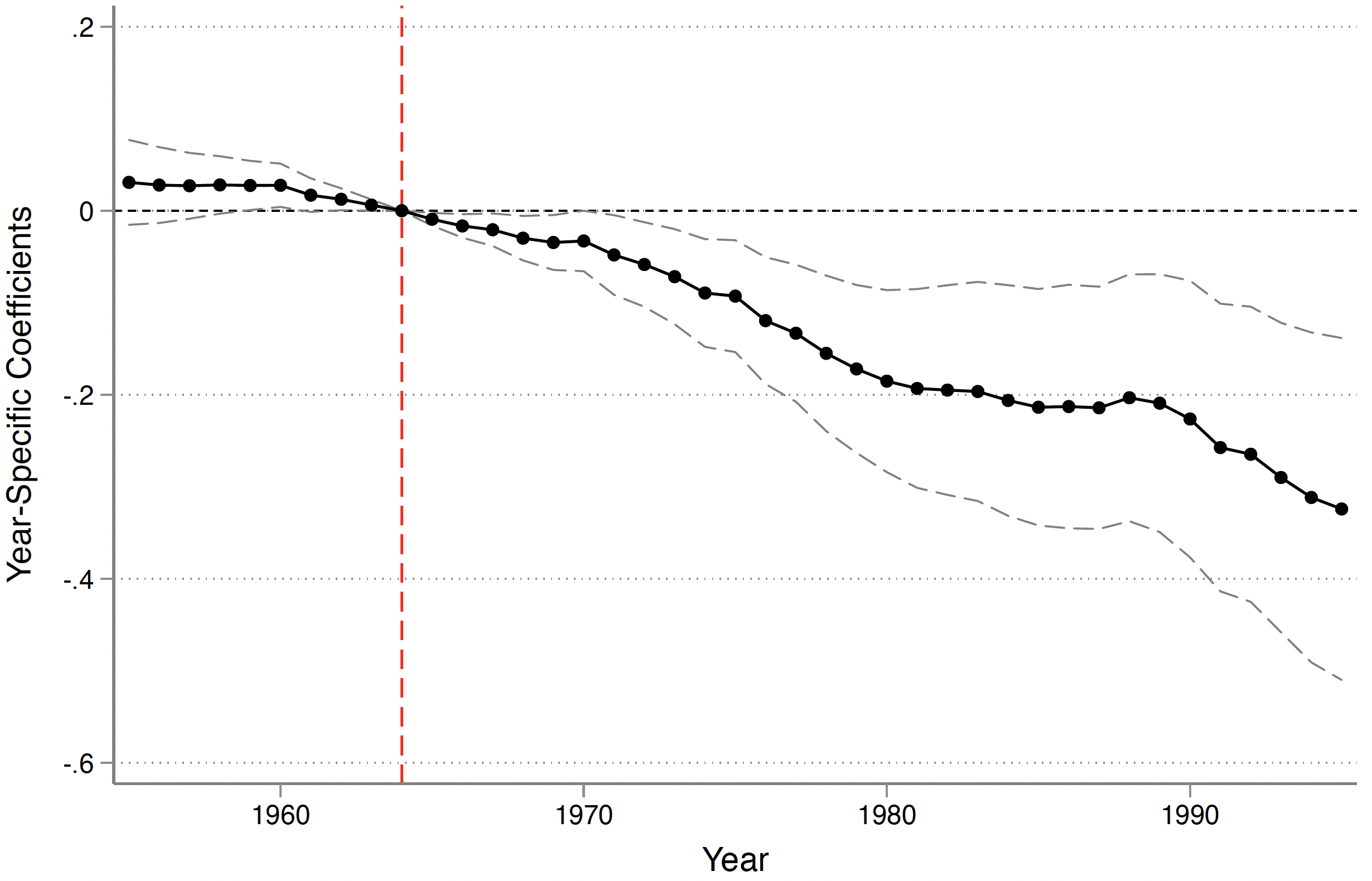

Figure 3 further focuses on schooling reforms through a classic event study design that compares birth-cohort born just before and just after a reform of the educational system, such as an increase in compulsory education age. The figure shows what we would expect: cohorts that are more likely to stay in school due to the policy reform are also less likely to work in agriculture several decades after. Schooling liberates individuals from farms by equipping them with skills more valued in the non-agricultural sectors.

Figure 3 Event study of education reforms on agricultural employment and schooling

(a) Cohort effects

(b) Years of schooling

Notes: the figure shows the estimates from event study designs around educational reforms, for cohort effects in agricultural employment (panel a) and cohort-level schooling (panel b).

Understanding the aggregate effects: General equilibrium matters!

To better understand the implications of our empirical results, we develop a theoretical model. We consider an economy with two sectors – agriculture and non-agriculture – where workers belonging to different birth-cohorts choose which sector to join and how much human capital to accumulate. This framework captures the traditionally emphasised drivers of structural change in the literature – unbalanced productivity growth and income effects – which are reflected by a decline in the demand for agricultural labour over time. Most importantly, given that skills are more useful in non-agriculture (De Pleijt et al. 2018, Mokyr et al. 2020), the growth in human capital across cohorts leads to a decline in the supply of agricultural labour.

Through the lens of this model, our empirical results can be used to show that the decline in the supply of agricultural labour is substantial; keeping prices fixed, it accounts for 40% of the global labour reallocation out of agriculture. The model also highlights that taking into account the general equilibrium forces is important, since when workers leave agriculture, agricultural wages and prices tend to increase. Considering these adjustments, we conclude that human capital growth contributes 20% of the overall observed reallocation out of agriculture.

Does human capital growth cause structural transformation or vice versa?

In our model, younger cohorts can invest more in human capital either as a response to lower demand for agricultural workers or for some other exogenous reasons, such as a lower cost of schooling or a change in mandatory education year. In either case, they would have a lower propensity to work in agriculture. But this leaves us with an open question: in which direction does causality run in practice? Is the increase in schooling across cohorts simply a consequence of structural transformation? Or is the educational expansion an independent cause of labour reallocation away from agriculture?

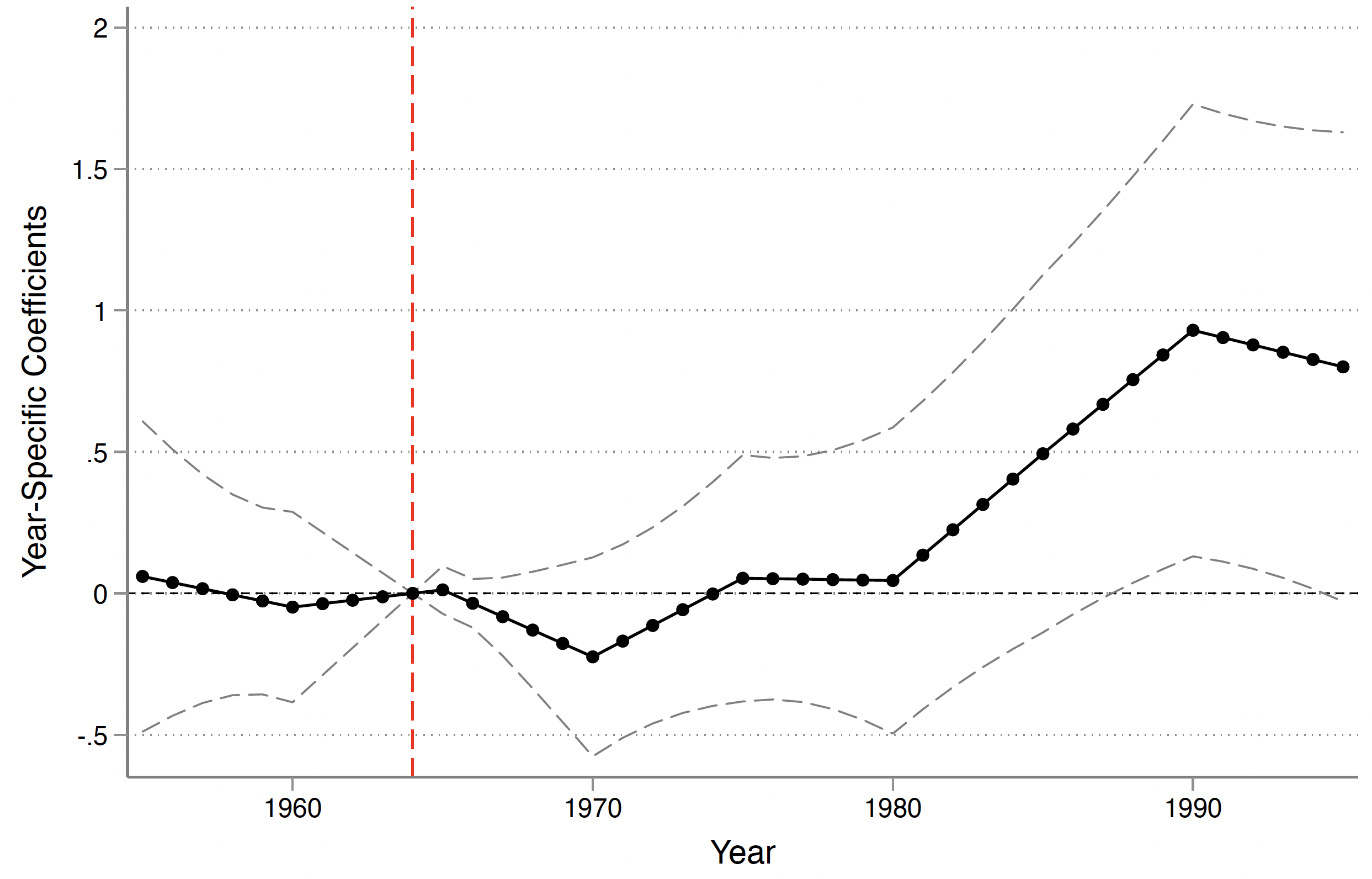

To address this question, we exploit a natural experiment given by the Green Revolution, previously studied in Gollin et al. (2021). Starting in the 1960s, the introduction of high-yielding varieties led to a dramatic increase in agricultural productivity growth. As shown in Figure 4a, countries that specialised in crops and were more exposed to these innovations saw a faster decline in agricultural employment, as higher productivity made labour less needed in agriculture. If human capital accumulation responded to lower demand for agricultural labour, then we should expect the affected cohorts in more exposed countries to stay longer in school; this is indeed what we find (Figure 4b). However, this effect is not as large as the overall increase in schooling we observe in the data. We conclude that the endogenous response to the decline in agricultural labour demand accounts for only about half of the overall growth in human capital. In other words, it is both true that human capital deepening causes structural transformation, and the other way around.

Figure 4 The Green Revolution: Event study estimates

(a) Log agricultural employment

(b) Years of schooling

Notes: the two figures plot the estimated coefficients and 90% confidence band of the interaction between year effects and the pre-Green Revolution production shares in wheat, rice, and maize. The dependent variables are the log of agricultural employment (Panel a), and the average years of schooling of the 5- to 10-year-old (Panel b). Both regressions additionally control for country and year fixed effects. The dashed lines show the 90% confidence bands. Standard errors are clustered at the country level.

Some final thoughts

Our work shows that the increase in human capital during the 20th century contributes to structural transformation, by equipping new generations of workers with skills more useful outside of the agricultural sector. This finding has important implications for policy. To the extent that human capital growth can be promoted by increased access to schooling and educational reforms (Agrist et al. 2021), these should be considered as potential tools to accelerate the economy-wide transition out of agriculture. At the same time, a word of caution is necessary. Formal education raises the ability and aspirations of workers to join the modern sectors, and thus the extent to which the labour market can absorb this change in supply becomes paramount. A failure to provide adequate jobs to this growingly skilled labour force would result in skills mismatch, workers’ frustration, and an overall waste of human talent.

References

Angrist, N, S Djankov, P Goldberg, and H Patrinos (2021), “Measuring Human Capital: Learning Matters More than Schooling”, VoxEU.org, 09 April.

De Pleijt, A, A Nuvolari, and J Weisdorf (2018), “Human Capital formation during the first Industrial Revolution: Evidence from the use of steam engines”, VoxEU.org, 20 October.

Duernecker, G, B Herrendorf, and AValentinyi (2018), “Structural Change and the Productivity Slowdown”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Gollin, D , C W Hansen, and A M Wingender (2021), “Two Blades of Grass: The Impact of the Green Revolution”, Journal of Political Economy 129(8), 2344–2384.

Herrendorf, B, R Rogerson, and Á Valentinyi (2014), “Growth and Structural Transformation,” Handbook of Economic Growth 2: 855–941.

Kongsamut, P, S Rebelo, and D Xie (2001), “Beyond Balanced Growth”, Review of Economic Studies 68(4): 869–882.

Mokyr, J, A Sarif, and K Beek (2020), “The wheels of change: Human capital, millwrights, and industrialisation in 18th-century England”, VoxEU.org, 30 January.

Ngai, L R, and C A Pissarides (2007), “Structural Change in a Multisector Model of Growth”, American Economic Review 97(1): 429–443.

Porzio, T, F Rossi, and G V Santangelo (2021), “The human side of structural transformation”, NBER Working Paper No. 29390.