An increasing number of papers document the global rise of concentration, profits, markups, and market power since the 1990s (e.g. Bajgar et al. 2019, De Loecker et al. 2019). Several factors – such as globalisation, digitisation, and the increased role of intangible assets and sunk costs – contribute to the observed patterns. Merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, as well as the (under)enforcement of merger control, have also been pointed to as likely determinants of increased concentration (Gutiérrez and Philippon 2018 ).

This trend is pervasive across industries and countries and is particularly pronounced in the digital economy. Companies active in digital markets – especially tech giants like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft – are aggressively involved in M&A, targeting and purchasing young start-ups that might fit their ecosystem. These acquisitions have a large potential to benefit consumers by allowing innovation to be scaled-up and integrated into richer and better-functioning platforms.

However, one growing concern for competition authorities is that such acquisitions may also have the objective of preventing the target company from ever becoming a competitive threat – as in the case of ‘killer’ or ‘zombie’ acquisitions1 – or cementing a dominant position in the market, thus making the entry of innovative challengers exceptionally difficult.

These patterns may be particularly problematic in the context of digital markets, where, due to strong network effects, competition is often for the market rather than in the market and where the competitive threat exerted by small market players or potential entrants is essential to discipline incumbents’ market behaviour (static efficiency) and foster innovation (dynamic efficiency).

Another reason for concern is that most of this M&A activity occurs under the radar of competition authorities. Because the targets are frequently start-ups still trying to figure out a viable path to monetisation, the vast majority of these transactions do not meet the turnover thresholds that trigger merger control.

These acquisition patterns have important implications for innovation and investments. The prospect of takeover by an incumbent can be an incentive for a start-up to develop potentially successful projects if it otherwise cannot get (enough) external funding to scale up and bring those projects to market. However, the incumbent may decide not to develop the project after the acquisition (see Fumagalli et al. 2020 for a discussion of the acquisition of potential competitors). Moreover, Kamepalli et al. (2019) point out that the prospect of being acquired by a dominant firm, if anticipated, could undermine consumer adoption of a hypothetical entrant’s product and thus scare venture capital away. Innovation in the ‘kill zone’ of the big tech companies appears not to even be financed.

Acquisition prospects may foster inefficient, duplicative innovation. Indeed, Cunningham et al. (2019) document that the real target of killer acquisitions in the pharma industry are R&D efforts of drugs falling in the same therapeutic market or using the same mechanism of action as the incumbent’s products. If the prospect of being acquired drives R&D, innovation incentives focus on the development of drugs that represent strong competitive threats (i.e. drugs for conditions already cured) – a social waste.

Acquisitions by big tech companies

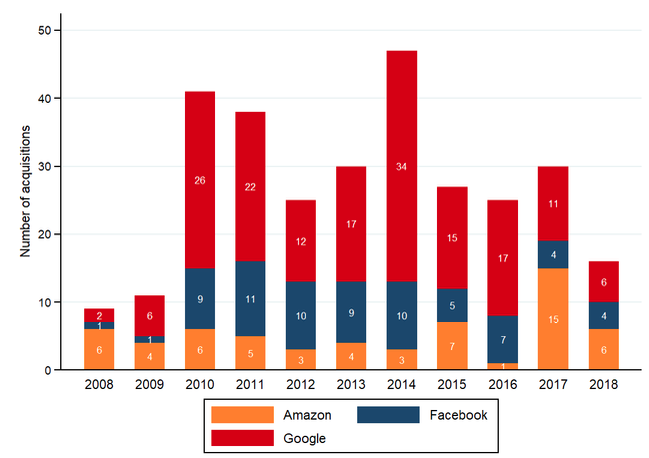

To better understand the dynamics of digital markets, we analysed the M&A activity carried out by Amazon, Facebook, and Google between 2008 and 2018 (Argentesi et al. 2019b).2 Over this period, based on publicly available information, Google acquired 168 companies, Facebook 71 companies, and Amazon 60 companies (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Acquisitions by Amazon, Facebook, and Google, 2008–2018

Source: Authors’ elaborations on Crunchbase data.

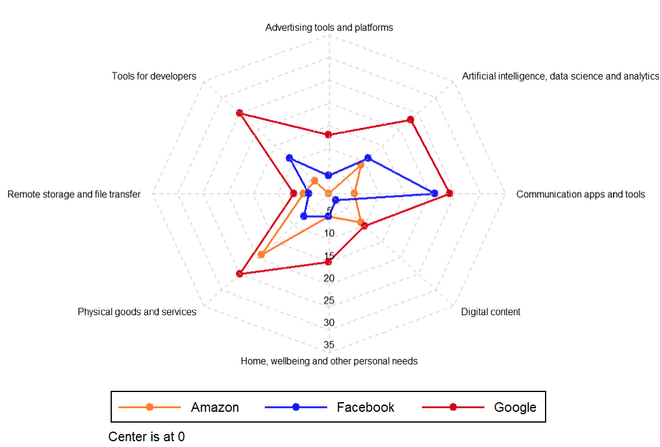

We then clustered target companies by their sector of economic activity. In terms of absolute volumes, Google has been much more active than Amazon and Facebook overall as well as in each of the clusters (Figure 2). Google’s acquisitions have been more heterogeneous in nature, whereas Amazon and Facebook seem to have focused more – but not exclusively – on companies that were active in their same area of economic activity (‘Physical goods and services’, and ‘Communication apps and tools’, respectively).

Figure 2 Acquisitions by Amazon, Facebook, and Google, by area of economic activity

Source: Authors’ elaborations on Crunchbase data

Some common trends can be identified. Amazon, Facebook, and Google have all propelled their push into mobile services by acquiring companies that developed services optimised for use from mobile devices. Moreover, they invested in companies with advanced data-analytics techniques (machine learning, artificial intelligence, analytics, and big data). These techniques are key for digital companies, which rely heavily on making predictions of various sorts to provide their services. Thus, these mergers can be expected to be efficiency-enhancing as they may enable incumbents to improve predictions.

Such improvements through external growth – complemented by the increasing collection of big data containing personal information and by pervasive network effects – may help these firms to reinforce their dominant position in their markets, and create insurmountable barriers to entry for competitors.

While these ex-post assessments cannot reveal the ‘killer’ or ‘zombie’ nature of these acquisitions, the above patterns suggest another potential anti-competition issue. By acquiring complementary services, incumbents may make it harder for entrants to develop competitive products.

Another striking feature of the acquisitions carried out by Amazon, Facebook, and Google is that their targets are often very young firms. While there are some outliers, nearly 60% of the targets are four years old or younger. The median age of the targets differs slightly across the three companies: 6.5 years for Amazon, 2.5 for Facebook, and 4 years for Google. A key issue for enforcement of merger control is that it is very difficult to assess the potential of very young firms to survive and become serious competitors for the incumbents in a way that stands up in court.

Issues in digital market merger policy: Facebook/Instagram and Google/Waze

To better understand how merger policy was implemented in these markets, we studied in depth two cases that were scrutinised by the UK authorities: Facebook/Instagram3 and Google/Waze.4 These acquisitions were among the very few mergers that underwent antitrust scrutiny – in the UK as well as abroad – out of the almost 300 cases identified above. The analysis of these decisions highlights potentially important issues in merger policy in digital markets.

First, the definition of the relevant market can be quite challenging for multisided platforms. Looking at functionalities – such as direct messaging and photo tagging – and the user side alone can be too limiting, as choices on the various sides of the market are closely intertwined.

Second, in both the Facebook/Instagram case and the Google/Waze case, data were almost not considered in the competition authorities’ investigation. However, data are a crucial asset in these markets and thus their role and related monetisation strategies should be considered in detail when outlining possible ways that the merger could negatively affect competition.

Finally, since it can be difficult to assess the degree of complementarity or substitutability – as well as the nature of competition – between services offered by the different platforms, a more dynamic perspective is warranted.

A key question in any merger retrospective – and especially for digital mergers – is whether the target companies could and would have grown to be viable competitors. Waze is still active but has never really managed to challenge Google Maps, the incumbent’s own product. Even ex post, it is hard to tell whether the potential of Waze was fully developed by the acquirer. Instagram has been very well integrated into Facebook’s ecosystem and was extensively developed to become a social media platform itself while keeping a distinctive focus on photo and video sharing. In this case as well, it is hard to assess whether Instagram could have leveraged its user base to invade Facebook’s turf.

Implications for competition policy

We highlight several implications for the development of competition policy in digital markets.

1. The volume of transactions by major digital platforms is substantial.

Yet, the overall acquisition strategy of these companies is not taken into consideration in merger control, which typically focuses on single transactions. Competition authorities might want to change this approach, especially in light of the discussion about stealth consolidation that leads to anticompetitive outcomes through a series of small mergers, which escape regulatory scrutiny (Wollmann 2019).

2. Targets are typically very young firms.

At this stage in their lifecycle, the evolution of the young firms is still uncertain, and it is difficult to identify the relevant counterfactual against which the effects of the merger should be assessed. Even if competition authorities use the tools available to them for information gathering (such as dawn raids), there will always be a certain degree of uncertainty with respect to the counterfactual chosen for the assessment of a merger. A more speculative counterfactual may fall short of meeting the legal tests competition authorities are required to satisfy to block a merger.

However, as high-tech markets evolve and pose new challenges, it may be necessary to test the boundaries of the substantive rules and of the applicable standard of proof so that competition authorities can effectively enforce merger policy.

3. Most transactions appear to be non-horizontal in nature.

This is the case, notwithstanding some notable exceptions – at least if competition authorities focus on relevant markets defined according to the between-application substitutability from the user’s point of view. Target companies operate across a wide range of activities, with their products and services often complementary to those supplied by major platforms. On the surface, this finding could be reassuring as it makes it less likely that the main objective of digital incumbents’ M&A activity is to prevent targets from becoming a competitive threat. In addition, non-horizontal mergers present significant scope for efficiencies.

However, the acquisition of firms active in different (often complementary) markets may generate only small efficiencies for giant companies that already rely on a large amount of data, whereas such acquisitions could be essential for smaller competitors that want to achieve the scale, diversity, and reach necessary to compete vis-à-vis the incumbents. This is a theory of harm that has not been explored by competition authorities but that may be worth considering (possibly within the scope of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU). Finally, these patterns might be particularly worrisome for innovation if a kill zone exists.

References

Argentesi, E, P Buccirossi, E Calvano, T Duso, A Marrazzo and S Nava (2019a), “Assessment of merger control decisions in digital markets: Evaluation of past merger decisions in the UK digital sector”, report by Lear for the Competition and Markets Authority.

Argentesi, E, P Buccirossi, E Calvano, T Duso, A Marrazzo and S Nava (2019b), “Merger policy in digital markets: An ex-post assessment”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14166.

Bajgar, M, G Berlingieri, S Calligaris, C Criscuolo and J Timmis (2019), “Industry concentration in Europe and North America”, CEP Discussion Paper 1654.

Cunningham, C, F Ederer and S Ma (2018), “Killer acquisitions”, mimeo.

De Loecker J, J Eeckhout and G Unger (2019), “The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Fumagalli, C, M Motta and E Tarantino (2020), “Shelving or developing? The acquisition of potential competitors under financial constraints”, mimeo.

Gautier, A, and J Lamesch (2019), “Mergers in the digital economy”, mimeo.

Gutiérrez, G, and T Philippon (2016), “Investment-less growth: An empirical investigation”, NBER Working Paper 22897.

Kamepalli, S K, R Rajan and L Zingales (2019), “Kill zone”, mimeo.

Wollmann, T (2019), “Stealth consolidation: Evidence from an amendment to the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act", American Economic Review: Insights 1(1): 77–94.

Endnotes

1 ‘Killer’ acquisitions take place when the acquiring company discontinues the target’s product to avoid cannibalising its own product. In a ‘zombie’ acquisition, the acquiring company keeps alive the target’s early stage product but does not further develop it. Although these patterns are documented in the pharma industry (Cunningham et al. 2019), evidence for digital markets is still very scarce (see Gautier and Lamesch 2019 ).

2 This paper is based on a study on the ex-post assessment of merger control decisions in digital markets carried out on behalf of the UK Competition and Markets Authority (Argentesi et al. 2019a).

3 Office of Fair Trading Decision of 14 August 2012 in Case ME/5525/12 – Facebook, Inc. / Instagram Inc.

4 Office of Fair Trading Decision of 11 November 2013 in Case ME/6167/13 – Motorola Mobility Holding (Google, Inc.) / Waze Mobile Limited.