Court cases for corporate wrongdoing often result in a defendant undertaking an in-kind punishment in lieu of a cash penalty.1 In the US, in-kind settlements have long been used in environmental enforcement actions under the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Supplemental Environmental Projects Policy, with a stated goal of addressing environmental justice concerns in communities with low incomes and a high share of minorities. The policy allows defendants to reduce the assessed cash penalty for violations of environmental statues by volunteering environmentally beneficial projects in the location of the violation. While the OECD has encouraged more countries to adopt the US model (OECD 2009), recent changes in the US have restricted the use of in-kind settlements (US Department of Justice 2020). The implications of in-kind settlements are not straightforward, yet policies on their use are being made in the absence of any quantitative analysis.

In-kind settlements have the advantage of being able to target goods to a particular group, similar to in-kind benefit transfers, such as food stamps or housing assistance (Currie and Gahvari 2007), or to earmarking and placed-based policies (e.g. Siegloch et al. 2021, Ku et al. 2020). In the context of US environmental enforcement cases, in-kind settlements constitute the only instrument to direct resources raised through corporate penalties to communities that are victims of corporate violations.2

Targeting is further pronounced in the case of Supplemental Environmental Projects through the EPA naming environmental justice as a critical factor to evaluate in-kind settlements.3 However, whether or not such provision can effectively promote more in-kind settlements in communities subject to EJ concerns is not obvious ex-ante, since the actual allocation is ultimately left to the negotiations between defendants and the EPA, with input from communities. The correlation of pollution and socioeconomics has been well documented (for reviews, see Mohai et al. 2009, Banzhaf et al. 2018 and Banzhaf et al. 2019) but policies to combat environmental injustice directly, including the EPA's Supplemental Environmental Projects, have been so far little studied.4

In-kind settlements have also a dynamic feature that makes them unique from targeting and placed-based policies. One goal of penalties is to be punitive, in order to deter future violations. As observed in Armour et al. (2016), reputational sanctions following an enforcement action can be far more punitive than the monetary penalty per se. In-kind settlements, by providing some benefits to the firm in the form of improved reputation, may ultimately result in diminished deterrence. On the other hand, in-kind settlements could result in increased environmental quality if they improve firms’ goodwill, provide more incentives for communities to monitor and report violations, or enhance capital upgrades (Supplemental Environmental Projects can include the purchase of equipment for environmental improvements).

In a recent paper (Campa and Muehlenbachs 2021), we use the history of US federal environmental cases between 1997 and 2017 to estimate the implications of in-kind settlements for firms and communities.

Every year around 5,000 cases are brought against defendants for violating federal environmental statutes, such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. In the settlement of these cases, the EPA gives defendants the opportunity to volunteer environmental projects, which have to go above and beyond what would be legally required of the defendant. These projects span a wide array of interventions including, for example, lead abatement, retrofitting school buses, emergency equipment for the local fire department, as well as upgrades at the violating facility.

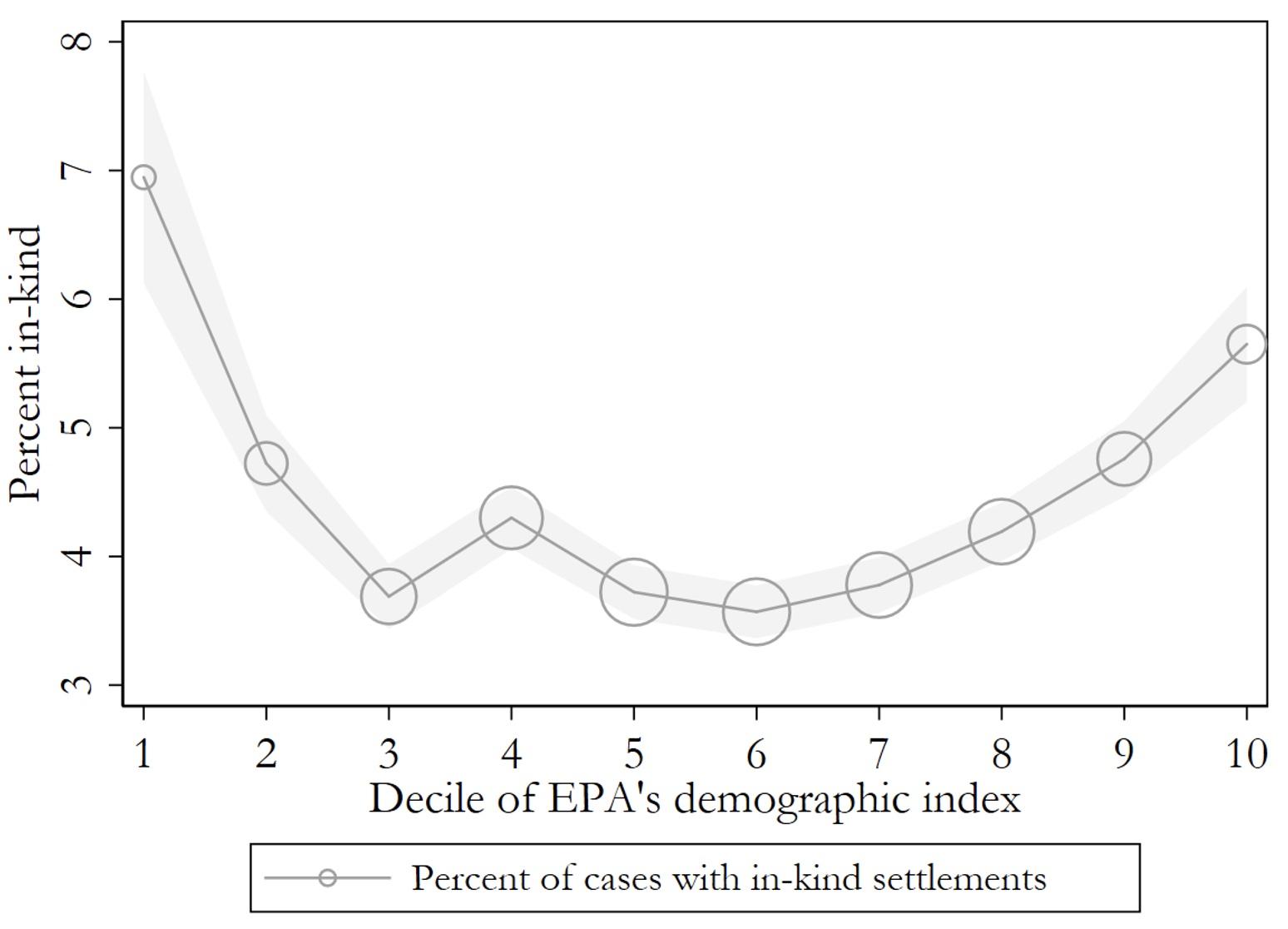

Our study of the location of Supplemental Environmental Projects shows that, as intended by the policy, a large share of cases settling in-kind occur in the decile with the highest share of minorities and lowest incomes, larger than most other deciles, but contrary to the intention of the policy, the largest share occurs in the cases involving the richest and whitest communities.5 Our findings suggest that the EPA's attempt to target environmental justice communities is less effective than systemic factors that determine settlement decisions.

Figure 1 In-kind settlements by decile of environmental justice susceptibility

Note: Markers designate the percentage of cases which resulted in one or more in-kind settlements, for each decile of EJ susceptibility. Following the EPA, a zip code's susceptibility is calculated as the average between the percentage low income and percentage minority and the decile is determined from the nation-wide distribution of zip codes. The size of each marker indicates the number of cases in each decile bin and the grey area designates one standard deviation above and below the mean percent.

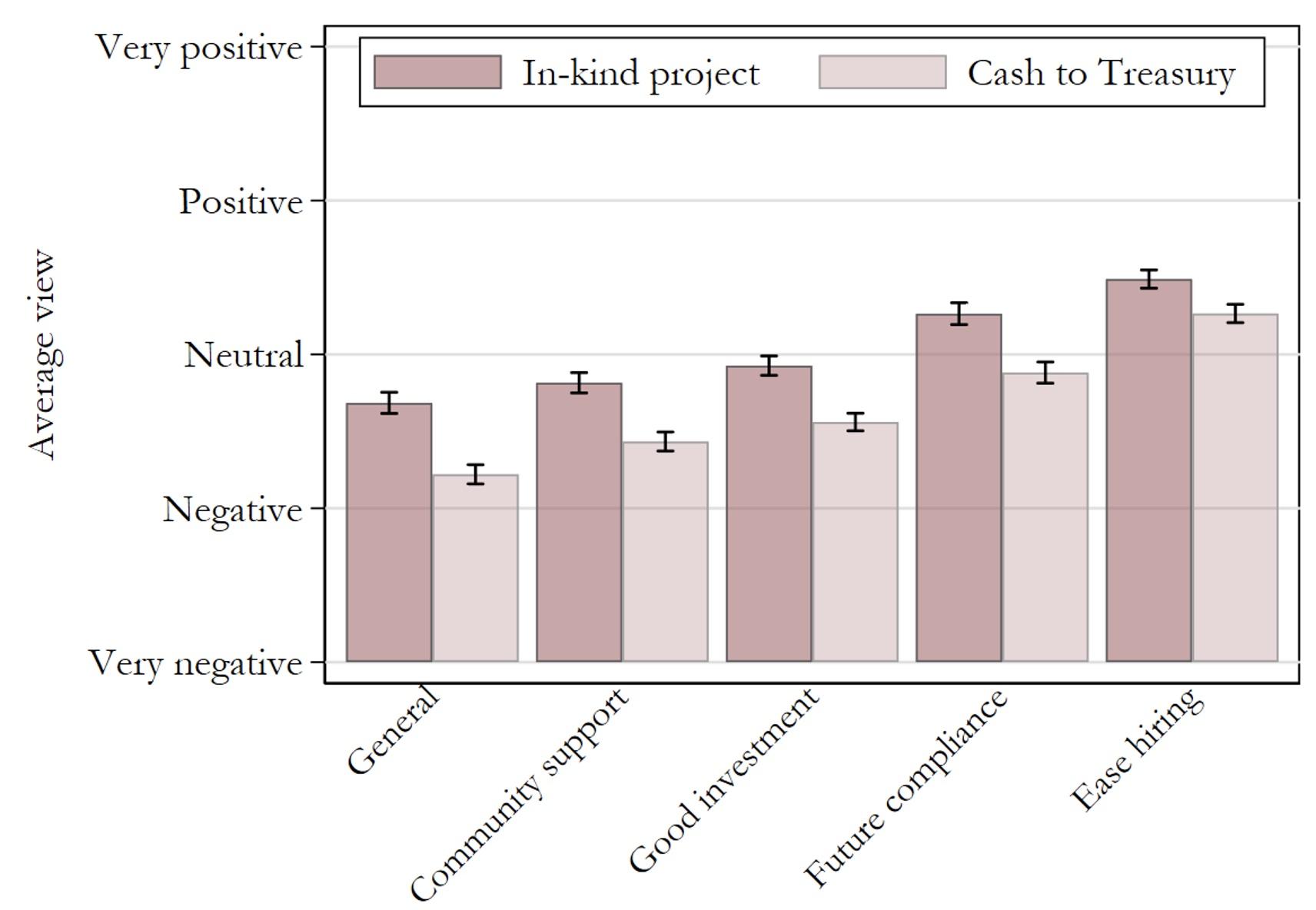

To test for leniency of in-kind settlements, we conducted a randomised survey on a representative sample of nearly 2,500 US residents. We find evidence that in-kind punishment has a positive impact on the public perception of a violating firm. In the survey, we randomly assigned respondents to read a description of a hypothetical settlement, involving either a cash payment to the US Treasury or an in-kind project to the violated community, and then asked respondents to express their perception of the violating company (e.g. how good of an investment the company would make or their overall feeling toward the company). Survey respondents that were given the in-kind treatment had a much more favourable view of the company, even though the company was guilty of the same violation.

Figure 2 Randomised survey: Perception of firm by settlement type

Note: Participants were given information about a company violating the Clean Air Act and randomized into two groups, based on whether the violation resulted in an in-kind or a cash settlement. After reading the violation and settlement type, participants were asked to indicate where their opinion about the company fell between two opposing statements. To depict their responses on the same figure, we categorized their responses to fall on a scale between very negative and very positive. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Our survey results also show more generally that the public has a strong preference for targeted in-kind projects over cash to the US Treasury, especially when the projects would benefit environmental justice communities.

Does the positive view of in-kind settlements have tangible consequences for the firms involved? To investigate this question, we use data on share prices of defendants and measure whether the announcement of a firm volunteering an in-kind settlement is associated to a different stock-market response from the announcement of a firm paying a cash penalty.6 Our stock-market findings are in line with the survey findings. While there is no significant difference in abnormal stock-market returns by settlement type before the settlement announcement, the stock-market response to the announcement is asymmetric: large cash settlements are associated with a negative stock-market reaction, whereas the response to quantitatively comparable in-kind settlements is positive. All in all, the stock market analysis and survey experiments strongly suggest that, even though in-kind settlements arise out of wrongdoing as much as cash settlements, they provide relatively more benefits to violating firms. The findings are in line with recent evidence that more developed stock markets increase the incentives of dirty industries to undertake a green transition, as argued in De Haas and Popov (2018).

Figure 3 Abnormal stock-market returns by settlement type

Note: The figures depict the average abnormal returns for different windows around the settlement date, for a selected sample of large settlements (i.e. total monetary penalty larger than the 90th percentile). Darker line depicts the average abnormal return from a cash settlement and the lighter line the difference in average abnormal returns between cash and in-kind settlements. The x-axis labels represent the window over which we estimate the average abnormal return. Following the literature, each window starts at one day before the final order is issued or lodged. For example, the label “5” refers to the average abnormal return between one day prior and six days after the order is issued, and “-5” refers to the average return between the one day prior and four days prior. The shaded areas depict 95% confidence intervals.

The potential implications for future environmental quality, as well as the largest likelihood of in-kind settlements occurring in non- environmental justice areas, beg the question of whether we can do better than the current allocation of in-kind versus cash settlements. To answer this question we consider the decision problem of whether to mandate a cash or an in-kind penalty as if it belonged to a social planner.7 The decision is a dynamic one, involving two trade-offs: (1) the current-period payoff of a local environmental improvement in one community versus the corresponding cash amount going to the US Treasury; and (2) a future-period trade-off that depends on how the settlement type chosen changes environmental quality in the future. The decision varies by community, depending on the degree to which a community faces environmental justice concerns.

The results from estimating the model can be summarised as follows. First, differences in future environmental outcomes by settlement type are small, yet overall in-kind settlements lead to more environmental improvement than degradation. Second, we predict that leaving the allocation up to the negotiation between firms and the EPA is consequential for the frequency of in-kind settlements. If a social planner had allocated in-kind settlements weighting all communities equally, the number of in-kind settlements during the period studied would have been nearly 7% larger. The increase in in-kind settlements would have been especially striking if the social planner had targeted communities most vulnerable to environmental justice concerns (a ‘Rawlsian’ social planner): the number of in-kind settlements, all destined to such communities, would have been 61% higher. Put it differently, given the desire to address vulnerable communities, if the EPA could mandate in-kind settlements we would likely see them more frequently, because, unlike the cash option, they allow targeting, and appear beneficial to the community in terms of future environmental quality. Our estimates also suggest that the welfare cost from the EPA not being able to mandate in-kind projects is small, although larger when we assume that, if allowed, the EPA would be ‘Rawlsian’; moreover, in such case all the welfare cost is borne by the most vulnerable communities, whose welfare arguably we should be especially concerned about.

In response to the suspension of Supplemental Environmental Projects in civil judicial cases, our paper suggests that on economic grounds, the use of Supplemental Environmental Projects is beneficial and worth continuing. The US experience suggests that environmental agencies worldwide can fruitfully use in-kind settlements as recommended by the OECD (OECD 2009); their effort would be likely met with large support from the public and the regulated community and is unlikely to have large consequences for deterrence.

References

Armour, J, C Mayer, and A Polo (2016), “Regulatory sanctions and reputational damage in financial markets”, VoxEU.org, 24 March.

Banzhaf, H S, L Ma, and C Timmins (2019), “Environmental justice: Establishing causal relationships”, Annual Review of Resource Economics, forthcoming.

Banzhaf, S, L Ma, and C Timmins (2018), “Environmental justice: The economics of race, place and pollution”, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Brady, J, M F Evans, and E W Wehrly (2019), “Reputational penalties for environmental violations: A pure and scientific replication study”, International Review of Law and Economics 57, 60–72.

Campa, P and L Muehlenbachs (2021), “Addressing environmental justice through in-kind court settlements", CEPR Discussion Paper 16293.

Currie, J and F Gahvari (2007), “Why In-Kind Benefits?” VoxEU.org, 17 December.

De Haas, R and A Popov (2018), “Finance and pollution”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Deryugina, T, N Miller, D Molitor, and J Reif (2021), “Air pollution policy should focus on the most vulnerable people, not just the most polluted places”, VoxEU.org, 13 January.

Karpoff, J M, J R Lott Jr, and E W Wehrly (2005), “The reputational penalties for environmental violations: Empirical evidence”, The Journal of Law and Economics 48 (2), 653–675.

Ku, H, U Schӧnberg, and R Schreiner (2020), “Place-based payroll taxes and regional employment”, VoxEU.org, 15 February.

Mohai, P, D Pellow, and J T Roberts (2009), “Environmental justice”, Annual review of environment and resources 34, 405–430.

OECD (2009), Ensuring environmental compliance: Trends and good practices.

Siegloch, S, N Wehrhöfer, and T Etzel (2021), ”Regional firm subsidies: Direct, spillover, and welfare effects”, VoxEU.org, 4 June.

US Department of Justice (2020), Memorandum on Supplemental Environmental Projects (“SEPs”) in civil settlements with private defendants, March.

US Environmental Protection Agency (2015), United States Environmental Protection Agency Supplemental Environmental Projects (SEP) Policy, Update.

White, B (2003), “$1.4 Billion Wall Street Settlement Approved: Federal Judge Accepts Conflict-of-Interest Deal”, Washington Post, 1 November.

Endnotes

1 For instance, in a historic 2003 settlement following charges of investors’ abuse, ten US securities firms agreed to pay $1.4 billion in penalties, including around $500 million to fund independent research and promote investor education (White 2003).

2 Congress has the exclusive power over federal government spending, the so-called ``power of the purse." Therefore, according to the Miscellaneous Receipts Act (33 U.S.C. 3302(b)), all penalties must be paid by the government official receiving the monies to the US Treasury.

3 The EPA's in-kind policy states that “...because promoting environmental justice through a variety of projects is an overarching goal, EJ is one of the six critical factors on which SEP proposals are evaluated... SEPs that benefit communities with EJ concerns are actively sought and encouraged.'' (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2015)

4 Related to the evaluation of policies to address environmental justice concerns, Deryugina et al. (2021) analyse the merits of targeting the most vulnerable populations rather than the most polluted places for policy-driven environmental improvements.

5 To investigate where in-kind settlements are more likely to occur, we categorize census block groups using the EPA's proxy for susceptibility to environmental justice concerns, specifically a demographic index based on income and race in the location of the violation.

6 For various reasons investors may view settlement type differently: the ultimate cost associated with in-kind settlements is uncertain, and the in-kind settlement might improve the firm's reputation, as suggested by the survey. Recent papers have examined the stock-market impact of environmental enforcement actions (Karpoff et al. 2005, Armour et al. 2016, Brady et al. 2019), but so far no attention has been paid to the difference between cash and in-kind settlements.

7 The framework that we develop is normative, because, as noted above, the actual allocation is not made by a social planner but rather by negotiations between firm and regulator, with input from communities.