In developing countries, intermediation costs and enforcement frictions constrain access to external finance for micro and small enterprises, leaving entrepreneurs' earning retention as a key source of funds for small business growth. But what explains entrepreneurial decisions to reinvest in their own businesses? This column reports on recent research using an MSE survey for over 6,000 entrepreneurs undertaken in Tanzania in 2010. The sample covers a large variety of enterprises in different locations, with entrepreneurs of different gender and educational profile, in different sectors.

What does theory and literature tell us?

There is a rich literature on savings practices in developing countries (see Karlan, Ratan, and Zinman 2013 for an overview). In addition to geographic, monetary and regulatory barriers, there are significant social constraints on savings behaviour, partly related to the position of the entrepreneur within the household. This is in line with a recent trend in development economics to increasingly consider intra-household negotiation (e.g. De Mel et al. 2008, Ashraf 2009). Previous research has linked participation in informal savings services, such as ROSCAs, to intra-household bargaining problems (e.g. Besley et al. 1993). Within-household savers might be less likely to reinvest because they suffer from the redistributive pressure resulting from the saved funds being held inside the household.

Building on the literature, a simple theoretical model that motivates our empirical tests shows that entrepreneurs are more likely to invest in their businesses if they save in a fashion which allows them easy access to their funds, such as formal savings accounts or personal saving mechanisms. This effect comes in addition to positive effects on reinvestment probability of productivity and borrowing capacity of the entrepreneur. Even endogenizing the decisions on how to save, introducing transaction costs of accessing more efficient (formal) financial services, we still find a positive effect of more efficient savings practices on the likelihood of reinvestment.

Our data

Our analysis is based on a novel enterprise survey conducted at the MSE-level in Tanzania. The survey data was collected by the Financial Sector Deepening Trust Tanzania in 2010 from a nationwide representative cross-section of 6,083 micro- and small enterprises. The respondents of the questionnaire are entrepreneurs with an active business as of September 2010. The median initial capital is about $35 and average monthly sales are $149. Half of the entrepreneurs are female. More than three quarters of the entrepreneurs in the sample save for business purposes. However, there is considerable heterogeneity among saving practices of Tanzanian entrepreneurs. Informal individual saving is the most popular practice among Tanzanian entrepreneurs: 75% of the savers save informal-individually whereas around 13% of them save formally. The remainder save their funds via people outside the household such as members of ROSCAs and moneylenders, or give funds to household members.

The empirical results

To test whether an entrepreneurs’ reinvestment decision co-varies with differences in savings practices, we regress a dummy variable indicating whether the entrepreneur reinvests earnings into her enterprise or not on an array of dummy variables capturing different savings practices. Specifically, we distinguish between entrepreneurs who (i) save in a formal bank account, (ii) save informally under the mattress, (iii) save informally with family members, and (iv) save informally with people outside the households, such as in ROSCAs or with deposit collectors.

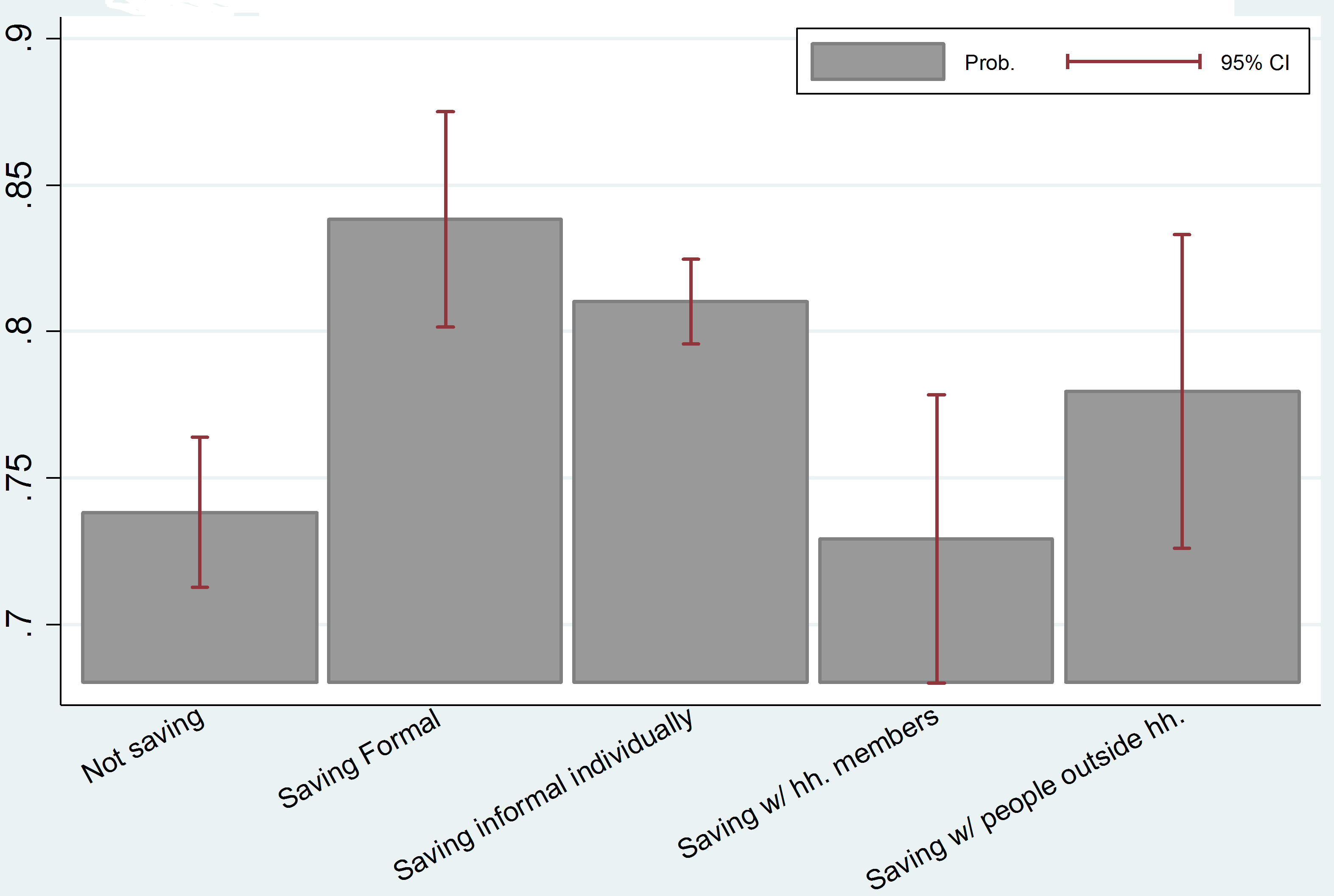

- The probability of reinvestment is higher for entrepreneurs who save than for those who do not. Specifically, entrepreneurs who save formally are nine percentage points more likely to reinvest and entrepreneurs who save informally are six percentage points more likely to reinvest than entrepreneurs who do not save. This is of economic significance given that 76% of all entrepreneurs in our sample reinvest.

- Within savers, the probability of reinvestment is higher for entrepreneurs who keep their savings in a formal bank account than for those who save informally. Specifically, the reinvestment probability is four percentage points higher for formal savers. This difference is driven by informal savers who save with others rather than under the mattress and who are nine percentage points less likely to reinvest.

- The lower reinvestment probability of informal entrepreneurial savers is driven by entrepreneurs who save with other household members. There is a 12 percentage point difference in reinvestment likelihood between formal savers and those who save with other household members.

Figure 1. Predicted reinvestment probability by saving categories

Figure 1 illustrates these findings, with the respective significance bands. These results hold when controlling for a large array of other entrepreneur characteristics, including gender, educational profile, marital status, income, and borrowing capacity. These results, however, might be tainted by endogeneity biases, so we run several robustness tests to address these concerns.

- First, we instrument the decision to save in a formal bank account with the geographic distance to nearest branch and the age of the entrepreneur. While a shorter distance increases the likelihood of saving formally, a higher age first decreases and then (after age of 52 years) increases the likelihood to save formally. Instrumenting savings patterns confirms our finding that formal savers are more likely to reinvest into their enterprise.

- Second, we explore whether the reinvestment gap between formal and within-household savers varies with specific entrepreneurial characteristics that might mitigate or exacerbate the negative effects from intra-household distributional challenges. We find that the reinvestment gap between formal savers and within-household savers is stronger for female than for male entrepreneurs and less strong for household heads. These differential effects are in line with theory that predicts a stronger reinvestment gap for those household members with more limited intra-household negotiation powers.

Conclusions

Our findings are consistent with and complementary to other recent evidence that access to formal savings services can be critical for microenterprise investment and performance. A recent experimental study by Dupas and Robinson (2013) in neighbouring Kenya shows that savers in formal bank accounts save and invest more in their businesses than entrepreneurs who do not save in formal banks. Brune et al. (2013) evaluate the effect of a commitment savings account on several outcomes for Malawian cash crop farmers. While these studies use randomized control trials to assess the effect of gaining access to a formal bank account, our study takes a broader view, comparing access to formal bank accounts with different informal savings mechanisms. Unlike the other study, we are therefore able to differentiate between the effects of entrepreneurial savings under the mattress, within the household and with others outside the households and – as we have shown – this is a critical distinction.

Our findings suggest that the entrepreneurs who need to protect their savings from consumption commitments of other household members may benefit most from the introduction of formal saving instruments in low income countries. Therefore, from a development policy perspective, targeting entrepreneurs who have low decision power in the household and facilitating their access to formal saving instruments could be thought as a priority.

Note: This research was funded with support from the Department for International Development (DFID) in the framework of the research project “Co-ordinated Country Case Studies: Innovation and Growth, Raising Productivity in Developing Countries”.

References

Ashraf, N. (2009), “Spousal control and intra-household decision making: An experimental study in the Philippines”, American Economic Review, 1245-1277.

Beck, Thorsten, Haki Pamuk, and Burak Uras (2014) “Entrepreneurial Saving Practices and Reinvestment: Theory and Evidence from Tanzanian MSEs”, Tilburg University mimeo.

Besley, T, S Coate, and G Loury (1993), “The economics of rotating savings and credit associations”, American Economic Review, 792-810.

Brune, L, X Giné, X, J Goldberg, and D Yang (2011), “Commitments to save: A field experiment in rural Malawi”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie, and C Woodruff (2008), “Returns to capital in microenterprises: evidence from a field experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4): 1329-1372.

Dupas, P, and J Robinson (2013a), “Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(1): 163-192. .

Karlan, D, A Ratan, and J Zinman (2013), “Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda” (No. 1027).