In his book, The Elusive Quest for Growth, Bill Easterly (2001) tells the fascinating story behind the emergence and rapid growth of the garment industry in Bangladesh (see also Rhee and Belot 1990). Between 1980 and 1986, the share of garments in Bangladesh’s total exports rose from 0.5 to 28.3%. The unprecedented take-off of the garment export sector is often attributed to 130 Bangladeshi workers—only four of them in management positions—who spent eight months in 1979 working and being trained in Korea as part of an agreement between their company, Desh of Bangladesh, and the Korean firm Daewoo.

The knowhow acquired by these workers seems to have been crucial in making Desh a highly successful exporter firm. Yet, perhaps more importantly, such knowhow eventually spilled over to the sector in general as workers moved to other firms or created new ones, contributing to the garment industry’s massive success as one of Bangladesh’s most significant export sectors.

Most of the economic debate on immigration has focused on its short-term labour market and fiscal effects. Perhaps because of this, less attention has been given to the long-run economic opportunities linked to migration. In our recent work (Bahar et al. 2019), we explore a novel angle exploring gains from migration: the role that returning migrants play in shaping industrial development and, more generally, contributing to the development of their home country.

Our study focuses on the early 1990s, when about 700,000 citizens of the former Yugoslavia fled to Germany escaping war. Most of the Yugoslavian migrants in the first half of the 1990s were given a temporary legal status, known as Duldung (German for ‘toleration’), that allowed them to stay and work in Germany. The Duldung status was valid for six months and automatically renewed as long as war was undergoing. In 1995 the Dayton peace agreements were signed, putting an end to the war in the former Yugoslavia. Consequently, Germany stopped renewing the Yugoslavian refugees’ Duldung status and started an enforced repatriation process. By 2000, the majority of Yugoslavian refugees had been repatriated back to their home country or to other territories of the dissolved Yugoslavia.

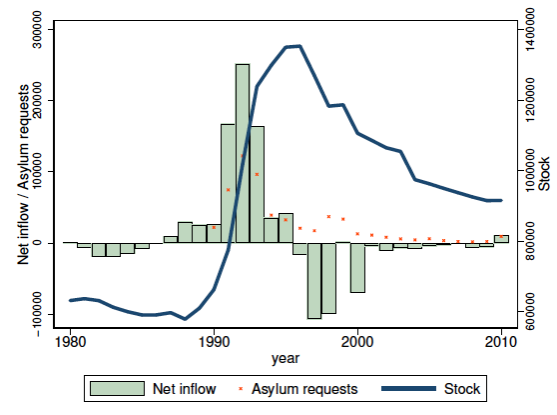

Figure 1 shows how the number of Yugoslavians in Germany changed during this episode. The stock of Yugoslavians in Germany, which was stable until the late 1980s, started to grow at a rate of 25,000 per year, up to and including the year 1990. This rate skyrocketed to 168,000, 250,000, and 165,000 in 1991, 1992, and 1993, respectively. The sharp increase in the net inflow of migrants was fuelled by refugees escaping war.

We also see a sharp increase in asylum requests from Yugoslavian citizens during the same years. After the Dayton Accord was signed, the number of Yugoslavians in Germany sharply declined, starting in 1996. By 2000, close to 350,000 Yugoslavians had left the country. While some of them left to a third country, it has been estimated that the majority returned to countries of the (by then) former Yugoslavia.

Figure 1 Stock and net inflow of Yugoslavian refugees into Germany

Notes: The figure shows the net inflow, stock, and asylum requests of migrants from (former) Yugoslavia into Germany, from 1980 until 2010. The number of migrant stocks by nationality is based on the Central Register of Foreigners (Ausländerzentralregister, AZR). The data have been downloaded from the GENESIS-online database of the German Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt), Table 12521-0002. Data on migration flows by nationality are from the migrations statistics (Wanderungsstatistik) of the German Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) and sent to us by request.

In our analysis, we use confidential administrative social security data from Germany that allow us to identify Yugoslavian refugees who had arrived in Germany during the Balkan refugee crisis and returned home after the war following 1995. In particular, we compute the number of these refugees who worked in each of the almost 800 four-digit tradable industries in Germany during that period (our ‘treatment’) and link this information to industry-level Yugoslavian export data. Using a difference-in-differences methodology, we estimate changes in export values from Yugoslavian countries to the rest of the world as a result of the return of refugees who were employed in those same sectors in Germany.

In order to address concerns of endogeneity due to self-selection of workers into certain industries, we exploit a spatial dispersal policy that exogenously allocated asylum seekers across the different regions of Germany upon arrival to construct an instrumental variable.

Using only raw data, Figure 2 visualises the total value of exports of products linked to different levels of treatment (i.e. quartiles), year after year. The figure shows that, up until 1995 (the year when our ‘treatment’ begins), products in the four different quartiles had somewhat parallel trends. However, after 1995, the third and fourth quartiles in terms of treatment intensity diverge significantly from the first two quartiles. This visualisation also suggests that the parallel trends assumption required for the difference-in-differences methodology is satisfied.

Figure 2 Exports for products with different levels of treatment

Notes: The figure plots the cumulative value of exports from the former Yugoslavia to the rest of the world (vertical axis) across the years. Treatment is defined as the number of return migrants from Germany by 2000.

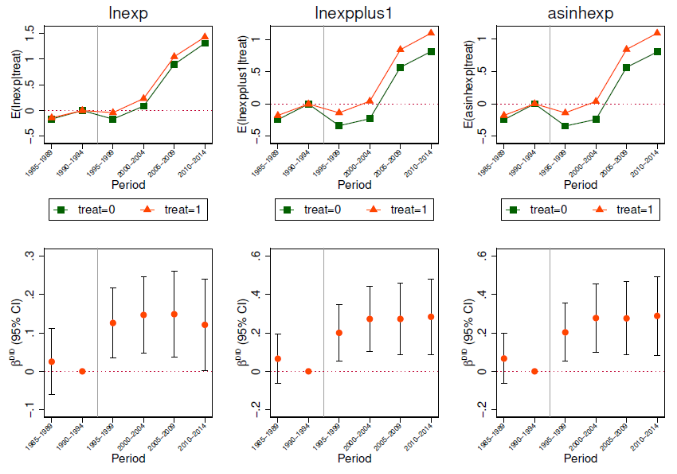

The trends observed with raw data are also confirmed in our econometric analysis. The main result of our paper is summarised in Figure 3, which visualises and compares industries with and without returning refugees in every five-year period before and after their return, which happens between 1995 to 2000. The upper panel shows the evolution of the expected value of exports (across our three different linear transformations) by five-year period for ‘treated’ and ‘untreated’ industries (e.g. industries with a significant number of returning refugees versus industries with none), while the lower panel shows the mean difference between these two categories.

Figure 3 Event study (five-year periods)

Notes: The top figure plots exports over time for industries with significant number of returning refugees (‘treated’) versus industries with none (‘untreated’). The dependent variable is the five-year average of exports (each column uses a different linear transformation and the period 1990–1994 is used as the base year). The bottom figure plots estimates for βDID for each five-year period, which corresponds to the difference between the two groups of industries plotted in the top figure. The results are estimated using 2SLS and include the convergence control. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals for the estimation.

It can be seen how the effect becomes positive and statistically significant starting in the period where the refugees start returning (1995 to 1999). Note that before their return, there is no differential pattern between those industries with and without returning refugees.

Our main analytical results indicate that industries with a 10% higher number of returning workers have a higher level of exports to the rest of the world of between 0.8% and 2.4% between the pre- and post-war periods. As shown in Figure 3, these positive effects remain stable and keep increasing as time goes by.

Our study rules out many explanations that could be driving the results, such as convergence, the inflow of investment linked to migration, or a decrease in information costs of international trade due to migrant networks. We also focus on the specific case of Bosnia, for which we are able to investigate economic outcomes beyond exports and find that, beyond higher exports, the presence of Bosnian refugees explain the higher number of firms and level of employment in the same sectors where the refugees worked while in Germany.

Which refugees are driving export performance?

The idea that migrants can play a role in shaping the comparative advantage of countries is part of a growing literature that links migrants and their descendants to the diffusion of knowledge (e.g. Kerr 2008, Choudhury 2016, Hausmann and Neffke 2016, Bahar and Rapoport 2018, Kerr 2018). Our results so far suggest this mechanism could be a plausible one. If this were the case, we should be able to see stronger results when looking at migrant workers more suited to acquire and transfer knowledge.

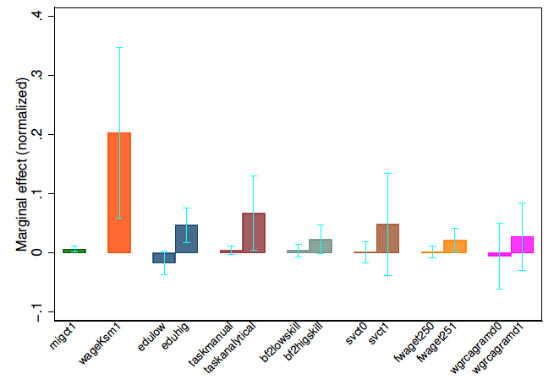

In order to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms behind the documented patterns, our paper exploits characteristics of the returning refugees, looking at their wages, skills, and occupations, as well as characteristics of their employers. Figure 4 summarises our results, presenting the estimated marginal effect of one additional returning refugee on exports by type of migrant. The first bar replicates the main results using the total number of returnees per industry, for comparison purposes, while other bars present marginal effects for each type of worker.

Figure 4 Marginal effect on exports, by type of migrant

Notes: This figure plots the estimated marginal effect of one migrant returnee on exports from the home country based on the levels of migrants of each type in the sample. Whiskers represent 90% confidence intervals. wageKsm1: worker’s last-seen salary while in Germany; eduhig: above high school level education; edulow: without post-secondary education; taskanalytical: workers in analytical-task-intensive occupations; taskmanual: workers in manual-task-intensive occupations; bf2highskill: workers in skilled occupations; bf2lowskill: workers in unskilled occupations; svct1: workers in occupations where they are more likely to act as supervisors (supervisory intensity); svct0: workers in occupations with lower supervisory intensity; fwaget251: workers employed by top-25% paying firms; fwaget250: workers employed by bottom-75% paying firms; wgrcagramd1: workers who experienced wage growth above median value; wgrcagramd0: workers with slower wage growth.

The marginal effect on exports of a worker’s salary (wageKsm1) is large and statistically significant. The marginal effect on exports of workers with higher educational attainment (eduhig) is also infinitely larger than for those with low educational attainment (given that the point estimate for the latter category is below zero). Similarly, workers in occupations intensive in analytical tasks (taskanalytical) are about 23 times more ‘effective’ than those in manual-task-intensive occupations. Workers in occupations that are considered skilled (bf2highskill) are about 35 times more effective than those in occupations considered unskilled.

Workers in occupations where they are more likely to act as supervisors are 25 times more effective than those in occupations where supervision is less common (though the difference is not statistically significant). Workers employed by the top 25% paying firms are, similar to the educational attainment category, infinitely more effective than those who worked in the bottom 75%. Similarly, a worker that experienced wage growth above the median value is much more effective than those with slower wage growth (though, again, not statistically significant).

All in all, these results suggest that the size of the effect on exports depends on the workers’ skills, the characteristics of their occupations, as well as who they work for and how successful they were in their jobs while abroad. These characteristics common to managerial roles make our results consistent with the growing literature emphasising the role of management as a crucial determinant of productivity (e.g. Bloom et al. 2012, 2013, 2018, Bloom and Van Reenen 2007).

Policy insights

Given that productivity is an underlying determinant of exports, we interpret these results as supporting the idea that migrants are drivers of knowhow and technology transfers between countries. This interpretation is backed by the fact that our results are particularly driven by industries that are knowledge-intensive, and are stronger when returnees are skilled, are in occupations intensive in analytical and cognitive tasks and in other managerial characteristics.

A lesson to draw from our results is the importance of integrating refugees in their host economies’ labour markets, as this can play a significant role in the post-conflict reconstruction of the refugees’ home countries upon their return.

References

Bahar, D, A Hauptmann, C Özgüzel and H Rapoport (2019), “Migration and Post-conflict reconstruction: The effect of returning refugees on export performance in the former Yugoslavia”, IZA Discussion Paper Series 12412.

Bloom, N, and J Van Reenen (2007), “Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4): 1351–408.

Bloom, N, B Eifert, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2013), “Does management matter? Evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 1–51.

Bloom, N, R Sadun and J Van Reenen (2012), “Americans do IT better: US multinationals and the productivity miracle”, American Economic Review 102(1): 167–201.

Bloom, N, K Manova, J Van Reenen, S T Sun and Z Yu (2018), “Managing trade: Evidence from China and the US”, NBER Working Paper 24718.

Easterly, W (2001), The elusive quest for growth, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Rhee, Y, and T Belot (1990), “Export catalysts in low-income countries”, World Bank Discussion Paper 72.