When the global real price of oil declined by about 65% between June 2014 and March 2016, many economic analysts expected a large boost to the US economy. For example, in December 2014, the IMF predicted that low energy prices would help accelerate US economic growth to 3.5% in 2016. As it turned out, average US economic growth increased only slightly from 1.8% per year before June 2014 to 2.2% after June 2014. By early 2016, the New York Times concluded that “it has been a truism of the American economy for decades: When oil prices rise, the economy suffers; when they fall, growth improves. But the decline in oil prices over the last two years has failed to deliver the usual economic benefits” (New York Times 2016).

Some observers have argued that the structure of the economy has fundamentally changed in recent years, making existing models of the transmission of oil price shocks obsolete. In two recent papers, we show that this conclusion is unwarranted (Baumeister and Kilian 2017, Baumeister et al. 2017). Notwithstanding some subtle changes in the transmission of oil price shocks to the US economy as a result of the US shale oil boom (Kilian 2017a), standard empirical models remain surprisingly useful for understanding why there was no strong stimulus.

Why the demand channel of transmission is more important than the supply channel

Oil price shocks may affect the economy by shifting domestic aggregate demand as well as by shifting domestic aggregate supply. In an oil-importing economy, unexpected oil price declines, all else equal, lower the cost of producing domestic goods and services. However, this cost or supply channel does not appear to be quantitatively important for the US economy. For example, there is no indication of a boom in the transportation sector (trucking, rail freight, air travel) after June 2014. Moreover, stock returns of companies that heavily rely on oil products as inputs in production (such as chemicals, rubber, and plastics) underperformed following the 2014-16 decline in the price of oil, while stock returns of companies catering to the needs of consumers (such as retail sales, tourism, and apparel) were much higher than average stock returns. The latter evidence suggests that the main channel of the transmission of unexpected oil price declines to the US economy is an increase in the demand for domestic goods and services, as consumers find themselves with more money in their wallet after filling up their cars at the gas station. When consumers spend this discretionary income on other goods and services, they create a stimulus for the domestic economy. Higher private consumer spending and business investment in turn has a multiplier effect on real GDP, if there is slack in the economy.

Oil price shocks as terms-of-trade shocks

The textbook model of the transmission of oil price shocks views an unexpected decline in the price of imported crude oil as a terms-of-trade shock, where the terms of trade are defined as the ratio of an economy’s import and export prices. As the terms of trade of the oil-importing economy improve, income is transferred from oil-exporting economies abroad to the US economy, creating a domestic stimulus. This basic insight, however, is incomplete because it assumes that imported crude oil may be used directly in production and consumption. In reality, no firm or consumer ever buys crude oil with the exception of refiners and some petrochemical companies. Rather, firms and consumers purchase refined products such as motor fuel. This means that we need to focus on the unexpected decline in the real price of motor fuel (henceforth referred to as gasoline) if we want to understand the implications of this terms-of-trade shock for private consumption. This decline is only about half as large as the unexpected decline in the real price of imported crude oil, given the cost share of crude oil in producing gasoline.

The consumption stimulus

Changes in the real price of gasoline affect the purchasing power of consumers to the extent that consumers spend their income on gasoline. It is straightforward to quantify the cumulative effects of unexpected changes in consumers’ purchasing power on private consumption by regression methods, accounting for changes in the dependence of the economy on imports of gasoline and crude oil. As less consumer income is transferred abroad, given the decline in the price of imported crude oil and hence in gasoline prices, consumers are able to spend more on other domestic goods and services. If there is slack in the economy, this increase in domestic demand, all else equal, raises real GDP. It can be shown that between June 2014 and March 2016, the consumption stimulus raised real GDP by 0.51%.

Are there asymmetries in the transmission of oil price shocks?

Conventional regression-based estimates of the US private consumption stimulus implicitly assume that the relationship between private consumption and unexpected changes in purchasing power is linear. This assumption is appealing because there is no compelling evidence of asymmetries in the transmission of oil price shocks to private consumption. Asymmetric responses to positive and negative oil price shocks may arise because of increased uncertainty about future oil and gasoline prices, in response to unexpected changes in the real price of oil or because frictions prevent the reallocation of labour and capital from the oil sector to other sectors of the economy. However, it can be shown that there is no evidence to support the notion that rising uncertainty about future oil and gasoline prices lowered private automobile consumption after June 2014, which casts doubt on the empirical relevance of this uncertainty channel. Nor is there evidence that the underemployment of labour and the underutilisation of capital in the US oil industry, caused by the decline in the real price of oil after June 2014, significantly slowed overall US growth. In fact, in most US states with a large oil sector, the unemployment rate between June 2014 and March 2016 declined. Even in North Dakota, which is heavily dependent on shale oil production, the unemployment rate rose only from 2.7% to 3.1%. Thus, frictions to the reallocation of capital and labour do not appear quantitatively important in the US economy either.

The investment stimulus

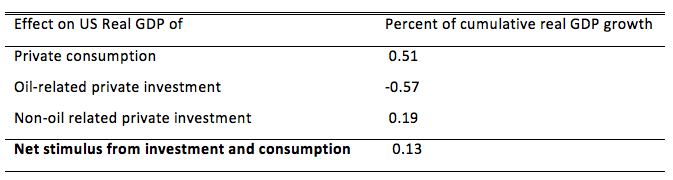

Unexpected oil price declines also affect investment spending. In discussing the investment stimulus from unexpectedly lower oil and gasoline prices, it is important to differentiate between investment spending by the oil sector and investment spending by other firms. Whereas most firms tend to benefit from lower oil prices, as domestic consumer demand increases, firms in the oil sector may actually cut their investment spending. Which of these two effects dominates depends on whether oil producers expect the price of oil to fall below the breakeven price for profitable oil investments, and how large the share of such oil investment projects is in overall investment. We show that the decline in oil investment lowers real GDP by 0.57% cumulatively, more than offsetting the cumulative increase by 0.19% caused by higher non-oil investment.

The net stimulus

Table 1 summarises the multiplier effect on US real GDP of the stimulus to private consumption and to non-residential investment created by the 2014-16 oil price decline. All estimates are expressed as cumulative percentage changes in US real GDP. Although non-oil business investment and private consumer spending jointly raised US real GDP by 0.7%, Table 1 shows that this increase was largely offset by the decline in the investment by the oil sector. The net effect on real GDP from unexpectedly lower oil prices has been only 0.13% (which is near zero when expressed in terms of average annual growth rates). Hence, the continued sluggish growth of the US economy after June 2014 is not a puzzle at all. It is exactly what we should have expected.

Table 1 The net stimulus from unexpectedly lower real oil prices, 2014Q2 to 2016Q1

Notes: All cumulative multipliers have been computed based on an import propensity of 15%.

What the analysis in Table 1 ignores is the fact that the 2014-16 oil price decline did not occur in a vacuum. It was associated in part with an unexpected slowdown of the global economy, which substantially lowered US export growth (Baumeister and Kilian 2016, Kilian 2017b). Controlling for this decline in exports, US real GDP between June 2014 and March 2016 would have increased by an additional 0.6%, but even this extra boost would only represent a modest overall increase in real GDP.

Concluding remarks

No one familiar with standard empirical models of the transmission of oil price shocks should have been shocked by the lacklustre performance of the US economy since June 2014. It is well documented that the consumption stimulus from lower oil prices is only modest, and the recent episode is no exception. Likewise, earlier studies of the large and sustained decline in the price of oil in 1986 already documented the sensitivity of US oil investment to falling oil prices, so the sharp decline in oil investment after June 2014 and the implied reduction in US real GDP growth should not have come as a surprise (Edelstein and Kilian 2007). Finally, it is well known that in analysing the macroeconomic consequences of declines in the price of oil, we need to take account of the overall state of the global economy and its implications for US exports.

References

New York Times (2016), “This Time, Cheaper Oil Does Little for U.S. Economy”, 21 January.

Baumeister, C, and L Kilian (2016), “Understanding the Decline in the Price of Oil since June 2014”, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 3: 131-158.

Baumeister, C, and L Kilian (2017), “Lower Oil Prices and the U.S. Economy: Is This Time Different?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Fall 2016: 287-336 (see CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11792).

Baumeister, C, L Kilian, and X Zhou (2017), “Is the Discretionary Income Effect of Oil Price Shocks a Hoax?”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11868.

Edelstein, P, and L Kilian (2007), “The Response of Business Fixed Investment to Energy Price Changes: A Test of some Hypotheses about the Transmission of Energy Price Shocks”, B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 7(1) (Contributions).

Kilian, L (2017a), “Global Repercussions of the U.S. Tight Oil Boom,” VoxEU.org, 2 April.

Kilian, L (2017b), “The Impact of the Fracking Boom on Arab Oil Producers”, Energy Journal 38(6): 137-160.