Like many other countries, Austria is currently facing unprecedented disruptions to everyday life. The global spread of coronavirus has led to a shutdown of vital functions of the economy and a massive increase in unemployment. While the countermeasures to reduce infections are largely undisputed among experts, the ways to deal with the economic crisis are very different across countries. In order to tackle skyrocketing unemployment in Austria, social partners have developed a new model of subsidized short-time work that could become an international role model. This policy is one of the key measures to mitigate the consequences of the Covid-19 economic crisis (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020, Caldera et al. 2020).

Short-time work reduces unemployment

Like many other OECD countries, Austria had already introduced short-time work (STW) during the Great Recession of 2008 (Hijzen and Denn 2011). The idea is straightforward: in order to stabilise employment and income, companies in need should reduce working hours temporarily rather than dismissing their employees (Giupponi and Landais 2020). The public sector then provides the remuneration for the reduced hours up to predefined thresholds. These measures aim at avoiding the social and monetary costs of unemployment, maintaining company-specific knowledge, and stabilizing consumer demand.

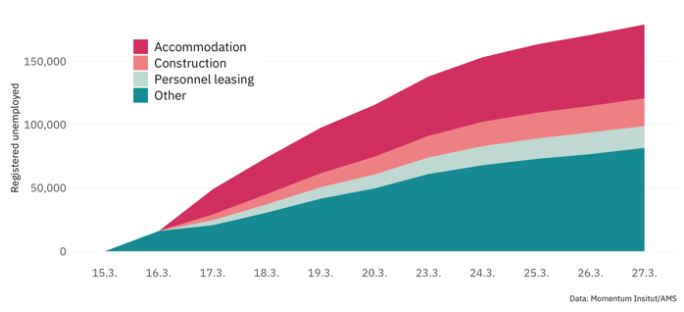

While there is ample empirical evidence that short-time work effectively reduced lay-offs during the Great Recession (Gehrke and Hochmuth 2017, 2020, Cahuc and Carcillo 2011, Boeri and Bruecker 2011, Mandl 2011), there was only a small share of employees that were affected by the policy in Austria. In 2009, roughly 1.2% of employees in Austria worked short-time, compared to almost 4% in Germany. The current crisis and the measures to mitigate the pandemic, however, have hit labour markets notably harder than in the Great Recession. After the Austrian government introduced massive confinement measures on 16 March 2020, unemployment soared by roughly 180,000 individuals within two weeks, from a total of 400,000 unemployed at the end of February (see Figure 1). The most affected sectors were accommodation, where the number of unemployed persons climbed by 178% within two weeks, and construction (+64%). Moreover, personnel leasing workers have seen a rise in unemployment by 39%. To counter this rapid increase in unemployment, the Austrian social partners negotiated a new short-time work model which was introduced on March 20. The budget for public income compensation was first limited to €400 million1 and has been raised €1 billion on 28 March,2 which is about 0.25% of Austrian GDP.

Figure 1 Rise in unemployment after announcement of confinement measures

Net replacement rates between 80% and 90% of previous income

The short-time work model allows a reduction in working hours while maintaining the employment relationship and granting almost full wage compensation. It even includes the possibility of a temporary reduction to as few as zero hours. Employees only have to carry out on average 10% of their normal working time within a time period of three months and it is possible to block that working time, for example at the end of the period. After these three months, it is possible to prolong short-time work for another three months if necessary. Depending on the former income level, the model grants income compensation of between 80% and 90% (including special remunerations).

In detail, the net replacement rates during short-time work are as follows:

- For previous gross monthly earnings of up to €1,700, the payment amounts to 90% of previous net earnings

- For previous gross monthly earnings of up to €2,685, the payment amounts to 85% of previous net earnings

- For previous gross monthly earnings of above €2,686, the payment amounts to 80% of previous net earnings

- For previous gross monthly earnings of above €5,370, there is no public compensation

- Apprentices receive full compensation (100% net replacement rate).

Thus, the short-time work grant from the Public Employment Service Austria (AMS) is much higher than regular unemployment benefits, which equal 55% of previous net income. In comparison to other countries (Schulten and Müller 2020), the Austrian short-time work model seems to be very attractive as the public replacement rate is high and the same across all sectors. In Germany the regular net replacement rate equals 60% and varies for sectors with collective bargaining agreements. In Norway, workers can be put on leave and receive full payment for the first 20 days and then between 80% and 62% depending on the salary. In Ireland, the net replacement rate equals 70%, in Denmark 75%, and in Great Britain about 80%.

Every company, independent of its size or branch of activity, can implement the short-time work model in Austria. The public sector refunds all additional costs and the company only pays for the actual working time. Employers also benefit because the wages and the social security contributions for the lost hours are omitted beginning with the first day of short-time work, while employees continue to be fully insured. As of 1 April, there have been 13,000 short-time work applications for roughly 250,000 workers, or 6.7% of all employees in Austria. At the peak of the Great Recession, there were about 37,300 workers (or 1.2% of all employees 2009) in short-time work.

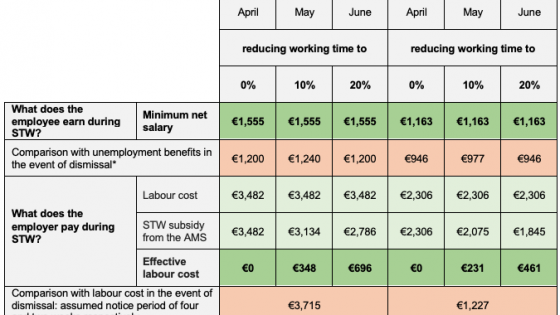

What do workers earn and employers pay?

Table 1 illustrates two typical cases for the Austrian short-time work model. The left panel shows Mr W. who normally works 38.5 hours per week in the metal industry and his gross monthly salary amounts to €2,651 (€1,829 net income). Due to the coronavirus, the firm reduces average working time by about 90% for three months. In April Mr W. does not work at all, in May he will work 10% (around 4 hours per week) and in June 20% (around 8 hours per week) of his former working time. Mr W. receives a stable public minimum net salary of about €1,555 each month during the STW period. The employer faces total effective labour costs of about €1,044 during these three months. In the event of a dismissal by the employer, the labour costs would be around €3,715 due to the notice period (four weeks), which is much more than the labour costs under STW, meaning that it is much cheaper for the company to retain Mr W. than to make him redundant. The right panel illustrates a worker in the service sector with a gross income of €1,751 (net €1,368). Even if the notice period in this case is only two weeks, there are additional costs of a dismissal for the employer.

Table 1 Two examples of short-time work compensation

Sources: AMS STW calculator; gross-net calculator, unemployment benefits calculator, own calculations.

Notes: Lost hours per month = lost hours per week multiplied by 4.33. Rounding differences may occur. Because of the different number of days per month, unemployment benefits differ each month.

Conclusion

During the Great Recession that started in 2007, many countries successfully implemented models of short-time work to secure jobs and stabilise demand. The current crisis caused by COVID-19 has revitalised endeavours to avoid major disruptions to the labour markets. Some 15 European countries have again adopted STW, but these models differ in their eligibility criteria, the cost for employers, the level of income replacement, duration, as well as country-specific institutional settings (Schulten and Müller 2020).

Facing rapidly increasing unemployment, social partners in Austria have negotiated a new and unique STW programme. It includes a public net income replacement of between 80% and 90% for three months and a temporary reduction in working time to as little as zero hours. While unemployment in March 2020 hit an all-time high since the end of WWII, there has been a large number of applications for short-time work that by far exceeds the levels during the Great Recession of 2008. This way, Austria is enabling a significant number of employees to keep their job and sustain consumption levels in order to mitigate the economic crisis.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds) (2020), “Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, A VoxEU.org Book, CEPR Press.

Boeri, T and H Bruecker (2011), “Short-time work benefits revisited: some lessons from the Great Recession”, Economic Policy 26(68): 697-765

Cahuc, P and S Carcillo (2011), “Is short-time work a good method to keep unemployment down?“, Nordic Economic Policy Review 1(1): 133-165.

Caldera, A, A Maravalle, L Rawdanowicz and A Sanchez Chico (2020), “Strengthening automatic stabilisers could help combat the next downturn”, VoxEU.org, 23 March.

Gehrke, B and B Hochmuth (2017), “Rettet Kurzarbeit in Rezessionen Arbeitsplätze?“, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 43 (1): 99-122,

Gehrke, B and B Hochmuth (2019), “Counteracting Unemployment in Crises: Non-Linear Effects of Short-Time Work Policy“, Scandinavian Journal of Economics.

Giupponi, G, and C Landais (2020), “Building effective short-time work schemes for the COVID-19 crisis”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Hijzen, A and D Venn (2011), "The Role of Short-Time Work Schemes during the 2008-09 Recession", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 115.

Mandl, I (2011), “Kurzarbeitsbeihilfe in Österreich”, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 37 (2): 293-314,

Schulten, T and T Müller (2020), “Kurzarbeitergeld in der Coronakrise”, WSI Policy Brief Nr. 38, 4/2020

Endnotes

1 https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2020_I_16/BGBLA_2020_I_16.html

2 https://www.bmf.gv.at/presse/pressemeldungen/2020/maerz/kurzarbeit-mittel-erhoeht.html