‘Modern monetary theory’ (MMT) has become a much-discussed topic in policy recently. While MMT has been known for some time, it has recently captured a lot of attention after US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York stressed its importance to boosting public spending for education and medical services earlier this year.1The growing emphasis on expansionary fiscal policy reflects the disappointing performance of unconventional monetary easing – including lower-than-expected economic growth and inflation performance, as well as various adverse side effects. Moreover, the global economic slowdown, rising relative poverty and inequality, and limited opportunity for additional monetary easing all support the case for fiscal expansionary policy.

MMT is consistent with the pro-fiscal policy view, but provides unique views about the role of government spending as well as zero-default risk on domestic currency-denominated government debt. It claims that governments never default on their own currency-denominated debt because the monetary sovereign government is the monopoly supplier of its currency (for example, Tymoigne and Wray 2013). Thus, government should increase public spending in the correspondent domestic currency – namely, reserve balances of designated financial institutions with the central bank – to achieve full employment as an employer of last resort and price stability without worrying about rises in the fiscal deficit and public debt.2 As the government is never financially constrained, neither taxes nor bond issuance to the market are necessary in order to finance public spending. MMT holds that expansionary fiscal policy can be sustained until substantial inflationary risk emerges, which in turn could be controlled through a tax hike. Taxes are not only treated as an inflation adjustment tool, but also used as a tool to increase public demand for the currency.

Salient features of MMT: The dominance of fiscal policy over monetary policy

The most salient feature of MMT is that fiscal policy is effective while monetary policy is ineffective for several reasons.

For starters, monetary accommodation or a cut in interest rates in a downturn does not necessarily generate sufficient private sector demand for credit when the outlook on firm profitability and household income remains weak.

Second, a cut in interest rates could be economically contractionary, since reduced interest income discourages active private sector spending. A cut in interest rates also promotes an unfair transfer of interest income from creditors to debtors, causing distortions in income distribution. For these reasons, a negative interest rate policy is dismissed by MMT. Similarly, monetary tightening or an interest rate hike in an expansionary phase does not necessarily contain credit growth and excessive inflation if domestic demand could be boosted by increased interest income.

Third, monetary easing tends to promote an accumulation of private sector debt and thus reduce private sector net wealth, as mentioned below.

Some of these points – especially those related to the effectiveness of monetary policy – seem to partially align with the fact that unconventional monetary easing conducted by major central banks after the Global Crisis generated disappointing results in terms of addressing aggregate demand, inflation, and long-term inflation expectations. In contrast, the government is able to increase employment directly by conducting various public projects. Another distinctive feature of MMT is that expansionary fiscal policy lowers interest rates rather than raising them – contrary to the widely shared view of the crowding-out effect in the loanable funds market. This feature could prevail if increased government spending raised reserve balances and place downward pressure on market interest rates.

Regarding the role of monetary policy, MMT emphasises that a central bank should support fiscal policy by maintaining interest rates at around 0% persistently and passively to maximise the effectiveness of the fiscal policy. Maintaining the low interest rate is conducted by an open market operation with commercial banks using government bonds. This means that the objective of monetary policy should be shifted solely to making fiscal policy as effective as possible – the conventional active role of stimulating/containing aggregate demand and inflation. This leads to a provocative conclusion that monetary policy cannot control inflation but can only control interest rates, which poses a major challenge to modern central banking practices that emphasise the price stability mandate and central bank independence.

Three conditions to justify MMT

These views or conclusions embedded in MMT have been controversial and have invited a lot of criticism, including the risk of hyperinflation, and the over-simplification of inflation dynamics and other elements of the actual economy in the model (such as an exchange rate depreciation), and the lack of political economy perspectives concerning the use of taxes as an inflation adjustment tool (Palley 2013, 2019, Summers 2019). Critics argue that the MMT claims are not consistent with the fact that many countries engaged in debt monetisation have historically experienced significant inflation or hyperinflation.

In my view, at least three conditions are necessary to justify MMT’s conclusions.

- First, public spending should intensively prioritise productivity-enhancing infrastructure, human capital, and innovation, which would raise potential economic growth and thereby prevent substantial inflation.

- Second, a government should issue its own currency rather than issue bonds through capital markets that are sensitive to investor sentiment and subject to volatility. To do so, dollarisation or the prevalence of a foreign currency in economic and financial transactions domestically should be avoided. The public needs to build up trust in a central bank and its issuing currency.

- Third, the private sector is able to increase corporate or household debt, but must achieve debt sustainability in the long run to avoid the banking and private sector debt crises in the future that would require painful debt restructuring. This reflects MMT’s view that government debt is more desirable and sustainable than private sector debt. This is because growing government debt could raise net financial wealth within the private sector and thus enhance wellbeing by allowing future consumption through saving today. In contrast, growing private sector debt reduces net financial wealth within the private sector and amplifies default risk. Monetary easing may promote an accumulation of private sector debt, possibly leading to future private sector debt and financial crises. Indeed, this point appears to be consistent with the reality that private sector debt crises occurred frequently globally in the past while public debt crises rarely happened in advanced economies in the contemporary era, where mature physical and social infrastructure are already in place and most government debt held by foreign investors are denominated in their own domestic currency.

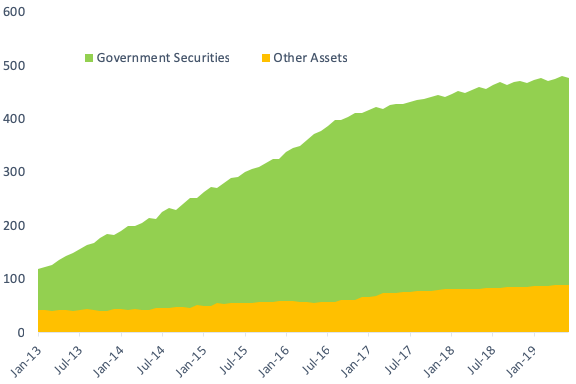

Implications of MMT for the case of Japan

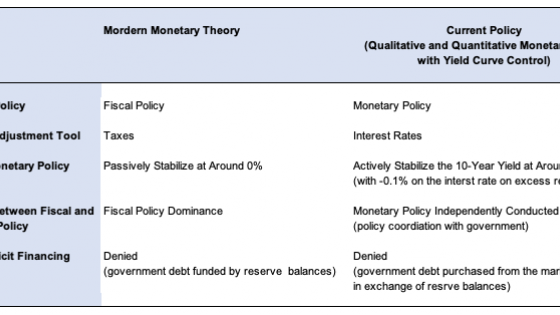

Professor Stephanie Kelton of Stony Book University, an MMT proponent, is of the view that Japan has been conducting MMT for some time.3 This statement invited discussions in Japan and is now viewed widely as a misunderstanding of the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy (Table 1). The misunderstanding appears to have stemmed from the seemingly-familiar circumstances such as the Bank’s large-scale holdings of government bonds and associated reserve balances, as well as the long-term interest rate stabilisation policy at around 0% under the yield curve control (Figure 1). Professor Kelton’s view was also rejected by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Governor Haruhiko Kuroda because of the government’s commitment to getting its fiscal house in order4 – even though the government goal of achieving a primary fiscal surplus has been long unfulfilled. It should be noted that the Bank of Japan purchases many government bonds from the market at negative yields – losing money by purchasing bonds at higher prices than face value.

Table 1 Features of MMT and the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figure 1 The Bank of Japan’s balance sheet (trillion yen)

a) Assets

b) Liabilities

Source: Bank of Japan.

What would be the implications of MMT for the Japanese economy if it were to be adopted? Japan’s level of household consumption has remained weak over the past two decades, reflecting stagnant real salary growth – mainly arising from low productivity growth. Households’ nominal disposable income has increased moderately in recent years but has remained below the 2000 level. Weak consumption is also attributable to concerns related to the rapidly-growing aging society, with an average life expectancy of 84 years in 2018. The public has been worried about limited pension benefits. Many people have questioned the sustainability of the national pension system – as evidenced by the relatively low non-payment ratio of compulsory pension premiums (about 30% currently) – especially among the young generation. It is associated with inter-generational cost-benefit imbalance problems, where current pensioners receive more in benefits than they paid while the younger generation is expected to pay more than current pensioners but receive less in benefits than current pensioners, since the national pension is basically a social insurance PAYG scheme (partially funded by government taxes and reserves).

To deal with weak consumption and low inflation issues, MMT proponents might recommend that Japan’s government increase pension and other social security benefits (for example, support for single mothers and aged widows) more generously and postpone the consumption tax hike scheduled for October 2019. Also, the government should increase productivity urgently by spending more on information networks, occupational training and engineering- and computer science-intensive education, as well as more R&D on healthcare, new drugs, and labour-saving medical treatment methods. MMT proponents might think this could work despite public debt accounting for 240% of GDP. The persistent current account surplus of over 3%, signalling excess production over domestic spending, could be another rationale for the government to spend more to increase domestic absorption and thus improve domestic living standards. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan would be instructed to maintain the current 10-year yield target set at around 0% under the yield curve control.

Is MMT really useful in Japan?

What are the blind spots in applying MMT in Japan? First, little economic slack is left in Japan due to the serious labour shortage coming from unfavourable demographics while underlying inflation (excluding volatile food and energy) remains weak and well below the 2% price stability target. Increased government spending may only exacerbate the labour constraint and squeeze private sector economic activities. The recent liberalisation policy to accept more temporary foreign workers is welcome but will not be enough to offset the labour shortage. Thus, MMT may not be a solution to Japan’s complex problems.

Second, adoption of MMT by the government would require good communication skills to convince households that the social security system will always be sustainable despite mounting ageing-related costs and the generous provision of pension benefits and health/elderly care services. However, should inflationary risk emerge, the government might be compelled to cut social security benefits as the sustainability of such a generous social security system diminishes. If households anticipate this event, concerns about ageing problems and the sustainability of the social security system will always persist.

Third, substantially low interest rates, long a fixture in Japan, may be sustaining zombie firms and discouraging vital corporate restructuring, exerting downward pressure on productivity growth. According to the Bank of Japan’s estimates, Japan’s potential economic growth has already declined from 1% in 2014 to less than 0.7% today, mainly due to a decline in total factor productivity (TFP) growth.5 The decrease in potential economic growth is likely to move toward 0.5% in the medium term due to tighter labour constraints. It is thus unclear whether current low interest rates, which do not necessarily reflect the credit worthiness of borrowers, would be good for Japan’s economy even though the crowding-out effect is eliminated.

Fourth, the adverse impacts of unconventional monetary easing on financial repression and market distortion are not well covered by MMT. Japan’s bond market has been distorted due to heavy intervention by the Bank of Japan, which already holds half of Japanese government bonds. The yield curve has been very flat, at low yield levels, and liquidity has become shallow. Profitability in the banking sector has declined due to lower lending-deposit interest rate margins and low yields on government bonds. Small banks have increasingly extended credit to lower quality borrowers and real estate projects in the face of the rising share of nondebt households and nondebt viable firms (Bank of Japan 2019). Housing prices have surged in metropolitan areas due to increased real estate development projects, scarce land, and increased construction costs arising from a shortage of construction workers and imported construction materials. Higher new home prices have reduced their affordability for general households, exerting downward pressures on aggregate demand. The risk of a real estate bubble in prime metropolitan areas is high and might occur after the 2020 Olympic Games, given the growing number of vacant old houses and apartments.

Conclusions

MMT provides the pro-fiscal policy view but provides unique views about the role of government spending as well as zero default risk on domestic currency-denominated government debt. MMT’s challenges centre on the implementation of its views, as the case of Japan demonstrates. One important issue is whether Japan’s government is able to keep increasing public debt and the Bank of Japan continues to stabilise the 10-year yield at around 0% for the future as long as the current low inflation and low interest rate environment continue to prevail.

References

Bank of Japan (2019), Financial System Report, April.

Tymoigne, E, and L R Wray (2013), “Modern Monetary Theory 101: A Reply to Critics”, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Working Paper no. 778, November.

Wray, L R (2012), “Introduction to an Alternative History of Money”, Levy Economics Institute if Bard College Working Paper no. 772, May.

Summers, L H (2019), “The Left’s Embrace of Modern Monetary Theory is a Recipe for Disaster”, Washington Post Opinion, March 4.

Palley, T (2013), “Money, Fiscal Policy, and Interest Rates: A Critique of Modern Monetary Theory”, IMK, FMM Working Paper no. 109.

Palley, T (2019), “What’s Wrong With Modern Money Theory (MMT): A Critical Primer”, IMK, FMM Working Paper no. 44, March.

Endnotes

[1] See here in Business Insider on Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (2019).

[2] Stephanie Kelton’s website and her explanation on CNBC Live TV on 4 March 2019, “Modern Monetary Theory Explained by Stephanie Kelton”. See also Bill Mitchell’s blog, “Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory”.

[3] Stephanie Kelton (2019), interview with Nikkei Newspaper (in Japanese).

[4] See article on Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s comments (2019) and Haruhiko Kuroda (2019).

[5] Bank of Japan website.