How do monetary policy shocks affect the distribution of income between workers and owners of capital? Do workers benefit relatively more when policy changes? Using evidence from five developed economies, we show that the share of output allocated to wages (the 'labour share') temporarily increases following a positive shock to the interest rate. This means that the slice of the pie enjoyed by those whose earnings are mostly made up of wages increases at the expense of profits and capital income. Strikingly, this redistribution channel that shows up in the data runs precisely in the opposite direction to the predictions of standard New Keynesian models commonly used to study the effects of monetary policy.

Despite its importance, there is no systematic empirical evidence on the effect of monetary policy shocks on the labour share. Yet, structural models widely used for monetary policy analysis (Galí 2015) rely on a transmission mechanism that has clear implications for the evolution of the labour share following a monetary policy shock.

Empirical evidence of the effect of monetary policy on the labour share?

In a recent paper (Cantore et al. 2018), we provide new econometric evidence on the effect of monetary policy surprises on the labour share for five developed economies (Australia, Canada, the euro area, the US, and the UK) from the mid-1980s until the Great Recession. As interest rates can vary for many reasons, identifying an exogenous variation in the rates that is attributable to monetary policy is a complex matter. To this end, we explored various approaches proposed in the literature.

We considered timing restrictions (Cholesky) – assuming that macroeconomic aggregates do not respond to the policy variable within the quarter – ‘reasonable’ and quantitatively loose restrictions (sign) – implying that a monetary tightening depresses the price level and monetary base growth – and, only for the US, instrumental variables restrictions imposing a correlation between the monetary policy shock and a narrative monetary series counterpart based on FOMC minutes (Romer and Romer 2004) or between the shock and the intraday variation of the Federal Fund rate in a narrow window around the monetary policy action (Gürkaynak et al. 2005, Miranda-Agrippino and Ricco 2017).

Figure 1 shows the impulse response functions (IRFs). The labour share temporarily increases after an identified surprise monetary policy contraction in all the economies under study. In our paper we also show that it is robust to using different measures of the labour share, sample periods, different sectors of the economy, and identification methods discussed above.

Figure 1 Responses over time of the labour share to a 1% increase in the short-term interest rate (using recursive Cholesky identification)

Note: Responses are reported in percent deviations.

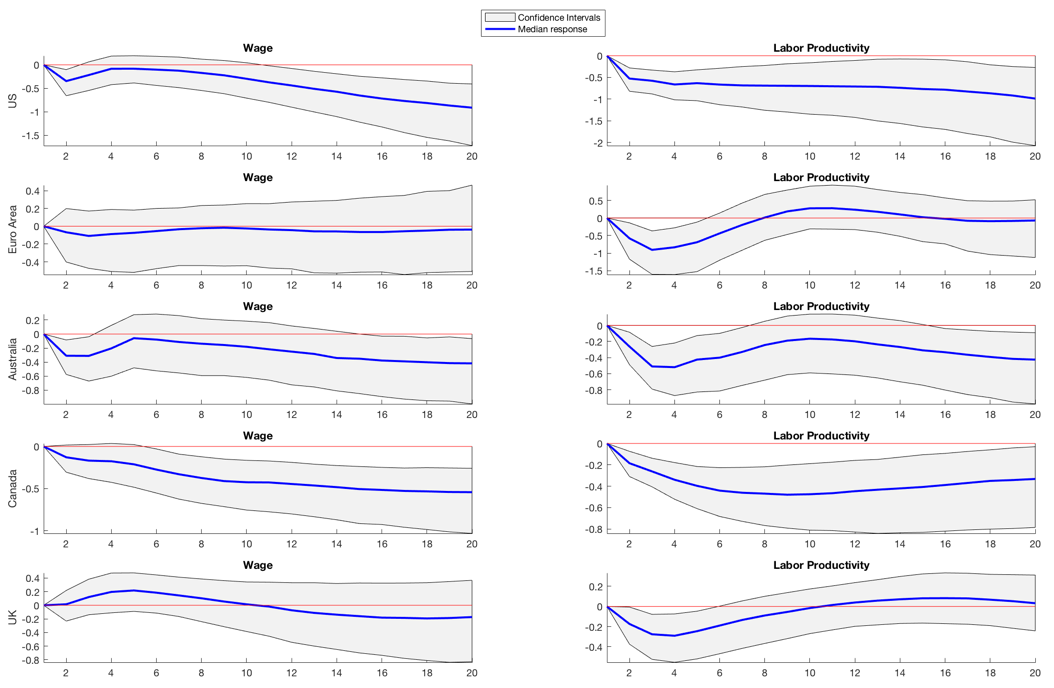

We then dig deeper into the transmission mechanism of monetary policy on the labour share by looking into its different components. The labour share can be decomposed into the ratio between real wages and labour productivity. Therefore, an increase in the labour share following a monetary tightening can occur from a movement in either component. Figure 2 reports the IRFs for each of the two variables for the same five economies. In each case, the reason why the labour share increases is that real wages fall (or do not increase) but labour productivity falls more. The fall in labour productivity can be rationalised with labour market frictions that make employment decline less relative to output. At the same time, nominal wage rigidities could explain why wages are falling (or at least not increasing) less than productivity.

Figure 2 Responses over time of the labour share components to a 1% increase in the short-term interest rate (using recursive Cholesky identification)

Note: Responses are reported in percent deviations.

What would simple New Keynesian models predict?

During the past few decades, New Keynesian models have been the principal theoretical means for economists to explore the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. In these models, monetary policy affects inflation and real economic activity through the effect of interest rate changes on the mark-ups that firms charge over their marginal costs of production. Changes in mark-ups redistribute income between labour and profits. A higher mark-up would imply a lower labour share.

The essence of that mechanism is as follows: a rise in interest rates will tend to reduce demand and when prices cannot adjust immediately, this implies that prices are too high relative to the new level of demand; they are not at their optimal lower level to equate demand and supply. Since prices are above optimal, firms are charging a higher mark-up. As mark-ups rise, the labour share of income falls and the profit share (mark-ups) increases.

But strikingly, the sign of this effect goes in the opposite direction relative to the empirical evidence shown above. This strong theoretical inverse relationship between the labour share and mark-ups has been used extensively in the literature debating the cyclicality of mark-ups (Nekarda and Ramey 2013, Bils et al. 2018).

Our results indicate a tightening increases the labour share – precisely the opposite of what the standard models would say.

Our approach differs from studies focusing on the cyclicality of mark-ups because the labour share (unlike mark-ups) is directly observable from national accounts and so does not require theoretical models to derive implied measures. Hence, we start from the data on labour share without any theoretical restriction and then compare the data behaviour with their theoretical counterparts.

We then analyse whether extensions of the simplest New Keynesian models can match the stylised fact that the labour share rises following a monetary tightening, studying different families of models commonly used in macroeconomics for the analysis of monetary policy.

Can a more elaborate model get the sign right?

As discussed, in the simplest version of the New Keynesian model (Galí 2018), the labour share is equal to the inverse of the price mark-up and hence is pro-cyclical following a monetary policy shock, contrary to our empirical evidence. However, this direct correspondence between the price mark-up and the labour share does not necessarily hold in other versions of the model. We analyse four ways in which the link between the labour share and the mark-up can be broken:

- models that consider fixed costs in production and a broader set of nominal and real frictions (Christiano et al. 2005);

- a cost channel of monetary policy which directly links the wage bill to interest rates (Phaneuf et al. 2018);

- complementarity between production inputs (Cantore et al. 2014); and

- models where wages are not set competitively but as a result of a bargaining process between workers and firms (Christiano et al. 2016).

Can different families of models that break the relationship between mark-ups and the labour share generate the dynamics of the labour share that we have documented?

The size and complexity of these models means that it is not straightforward to answer this question analytically. Instead, we explore numerically whether different combinations of behavioural and market structure parameters can generate the correct sign and magnitude for the response of the labour share. We derive measures of the labour share from the models and look at their response to a monetary policy shock. This is carried out using a three-step approach. We first look at the likelihood that these models can generate, at least a priori, the empirical responses from our SVAR using a Prior Sensitivity Analysis (Canova 1995) approach. Second, we single out the key model parameters driving the response of the labour share, real wages, and productivity using Monte Carlo Filtering techniques (Ratto 2008). Third, we estimate these key parameters by matching the models’ responses to a monetary policy surprise to those obtained in the data (Christiano et al. 2010). The intuition behind this approach is to check across a wide range of parameters rather than just focusing on a baseline calibration. The IRFs are shown below.

Figure 3 The empirical response of a variable to a monetary policy surprise (with uncertainty bands)

Notes: The coloured lines are the estimated responses from the different theoretical models. US data 1959Q2-2008Q4.

The key result is that standard models generate the ‘wrong sign’ for the effect on labour share when compared to the empirical results. This is not just a feature of the basic New Keynesian model, but carries over in more elaborate versions commonly used for monetary policy analysis. Several of the models do a reasonable job at matching the responses of standard macroeconomic variables to an identified monetary policy shock, but they are unable to reproduce the response of the labour share.

Conclusions

Our results emphasise that macroeconomics needs to develop models that are able to replicate the cyclical behaviour of the labour share and its components. So far, neither models with price and/or wage rigidities nor other relevant real frictions are able to match the dynamics observed in the data. Accordingly, using these models to analyse the distributional effects of monetary shocks could be misleading.

References

Bils, M, P J Klenow and B A Malin (2018), “Resurrecting the Role of the Product Market Wedge in Recessions”, American Economic Review 108(4-5): 1118-46.

Canova, F (1995), “Sensitivity Analysis and Model Evaluation in Simulated Dynamic General Equilibrium Economies”, International Economic Review 36(2): 477-501.

Cantore, C, M León-Ledesma, P McAdam and A Willman (2014), “Shocking Stuff: Technology, Hours, and Factor Substitution”, Journal of the European Economic Association 12(1): 108–128.

Cantore, C, F Ferroni and M León-Ledesma (2019), “The Missing Link: Monetary Policy and The Labor Share”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13551.

Christiano, L J, M Eichenbaum and C L Evans (2005), “Nominal Rigidities and the Dynamic Effects of a Shock to Monetary Policy”, Journal of Political Economy 113(1).

Lawrence J. Christiano, L J, M Trabandt and K Walentin (2010), “DSGE Models for Monetary Policy Analysis”, NBER Working Paper No. 16074.

Gal í, J (2015), Monetary Policy, Inflation, and the Business Cycle, Princeton University Press.

Gürkaynak, R, B Sack and E T Swanson (2005), “Do Actions Speak Louder Than Words? The Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements”, International Journal of Central Banking, May.

Miranda-Agrippino, S and G Ricco (2017), “The transmission of monetary policy shocks”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 657.

Nekarda, C J and V A Ramey (2013), “The Cyclical Behavior of the Price-Cost Markup”, NBER Working Paper No. 19099.

Phaneuf, L, E Sims and J G Victor (2018), “Inflation, output and markup dynamics with purely forward-looking wage and price setters”, European Economic Review 105: 115-134.

Ratto, M (2008), “Analysing DSGE Models with Global Sensitivity Analysis”, Computational Economics 31(2): 115-139.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (2004), “A New Measure of Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications”, American Economic Review 94(4): 1055-1084.