Is there a point where money just runs out? This question was recently asked by Trevor Noah to Gita Gopinath, the IMF Chief Economist,1 and reflects the current public dilemma. While the public generally approves of the massive interventions deployed by governments and central banks in response to COVID-19, they are also concerned about the long-term consequences on growth and inflation.

Of course, money never ‘runs out’.2 Governments can borrow and central banks can print money to finance the present public expenditures. However, these also involve taking on future risks. In a very simplified approach, we consider the two main financing instruments, debt and money creation, which are associated with default risk and inflation risk respectively. A good analytical translation of ‘money running out’ is to ask how best to manage the trade-offs between those risks. This column aims at presenting a framework to think about these issues.

The policy space

The post COVID-19 monetary and financial landscape will present three defining characteristics:

- a high level of public debt in all countries;

- central banks with very large balance sheets; and,

- a strong and immediate link between debt and monetary policy, since a significant part of government debt will be held by central banks themselves. This configuration is not unprecedented. It has been observed in the past after wars or natural disasters and has generally been accompanied by (moderate or strong) inflation.

However, history does not always repeat itself. The economy is not that deterministic. There is no necessary or automatic link between money supply and inflation. Nor is there a direct relationship between the volume of debt and its sustainability. Other factors play a determinant role, including: the demand for money and for safe assets, the real equilibrium interest rate, the expected growth and inflation rates over the longer term. Those factors are not independent of each other. Each of them is also driven by policy actions and depend on the policy regime.

Despite high initial debt/GDP ratios, the starting point is favourable in most advanced economies. This is mainly due to the conjunction of low interest rates and low inflation. Long term (equilibrium, real) interest rates have been low and decreasing for several decades. If they stay below growth rates in the future, as currently expected, they will have a stabilizing effect on debt/GDP ratios (Blanchard 2019). Should risk free rates unexpectedly rise, it would be partly good news. It's hard to see a scenario where this would happen without a significant acceleration in economic growth. And growth would go a long way towards resorbing any debt overhang that may exist.

Inflation – and inflation expectations – have been stubbornly low for most of the past decade. In fact, the main frustration for central banks has been their continuing inability to bring up those expectations closer to their targets. The case of the Bank of Japan, in particular, is noticeable. For many years, it has implemented policies very similar to those now deployed in other countries in fighting the COVID-19 crisis. For Japan, these policies had no significant impact on inflation.

Together, low interest rates and low inflation create, prima facie, a large policy space. It can be exploited to absorb the COVID-19 shock on public finances without fear of destabilising the economy. That space looks even larger if, in the years to come, central banks allow themselves to slightly overshoot their mid-range target of 2% inflation, to compensate for years of undershooting.

How best to use that policy space without destroying it? Two considerations are relevant.

First, the stability of inflation expectations: It is likely that contemporary inflation will be more volatile in the near future. There may be price shocks arising from disruptions in supply chains, rigidities introduced by social distancing, and sectoral upticks in demand. These shocks will temporarily push inflation up or down, with the balance highly uncertain (Brunnermeier 2020). They should not be a source of concern and should not trigger any policy reaction as long as expectations remain firmly anchored. This is clearly the case today, as shown by measures based on markets and surveys. However, an abrupt shift upward cannot be excluded – even with a low probability. In the past, financial markets have not proved very good in anticipating increases in inflation (Cochrane 2011).

Second, risk premia: Up until now, we have implicitly assumed that governments can borrow at the risk-free rate (generally below the growth rate). This is not true for a majority of sovereigns that have to pay a risk premium in the form of a spread. Very often, that spread is high enough to bring the interest rate over and above the growth rate, creating a problem of sustainability.

Risk premia reflect a mix of solvency and liquidity risks, in proportions that are hard to determine at any single moment in time. They depend on changing growth forecasts, as well as investors’ risk aversion and preferences for safe assets. Both on solvency and liquidity grounds, they are subject to self-fulfilling beliefs and multiple equilibria. The policy space can shrink brutally under the action of market forces. One crucial question for central banks is how far they should go (now and in the future) in counteracting those market forces and stabilising markets of public debt.

Money and debt

Consider a consolidated balance sheet of the government and central bank. From this perspective, central bank money (reserves) and government bonds appear very similar. Both are liabilities of the consolidated government. Both are, ultimately, backed by the future flow of fiscal surpluses. Today, both carry interest (as monetary policy is conducted by paying interest on reserves). When interest rates are at zero, reserves and short-term bonds are very close substitutes in the portfolios of investors

There are two differences however:

- Government bonds are redeemable at given dates, whereas reserves are not.

- Government bonds are generally issued with a fixed interest rate (coupon) for their whole life;3 by contrast, the interest rate on reserves is variable, depending on monetary policy decisions taken by the central bank.

The key point here is that bonds and reserves do not carry the same risk for the future. Bonds are exposed to default risk if solvency deteriorates. Whereas reserves carry an inflation risk if, for some reason, the central bank is not in a position to raise interest rates when necessary. In particular, when the amount of reserves is high, the central bank may be inhibited by the quasi-fiscal cost associated with paying interest on them. This possibility of ‘fiscal dominance’ may suffice to de-anchor inflation expectations (Sargent and Wallace 1981).

At the moment, monetary policy operates through the purchase of government bonds. It changes the structure of the liabilities of the consolidated government, but not its size.

It essentially amounts to transforming one form of liability into another. Doing so, it simply substitutes one form of risk to another. In the current policy environment, ‘monetisation’ is just a transformation of risks: from a credit and funding risk to an inflation risk.

Whether it is welfare enhancing depends on two questions. One is the negative value attached by the society to each of those risks respectively, should they materialise. This falls outside the scope of this column. The other question is the probabilities that they will in effect materialise.

Policy trade-offs

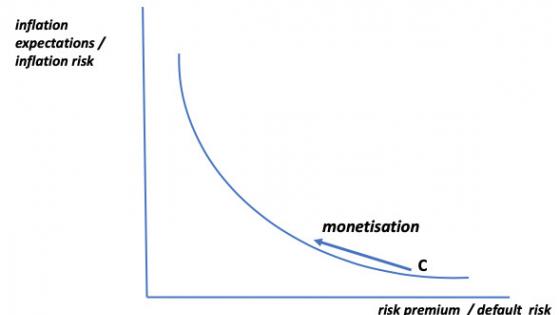

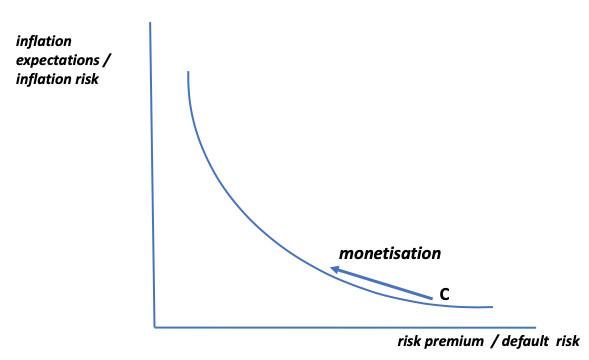

Within that simplified framework, we can represent the trade-offs faced by policymakers. Figure 1 shows the different combinations of risk premia and inflation expectations that produce the same amount of total financing, either through money or debt issuance. For every policy mix, there is a balance of risks and a corresponding point of the curve.

Figure 1

The curve moves up with the amount of financing that is needed. It moves down and left when growth expectations improve (as risk premium get smaller). Remarkably, it also moves left and down (and the slope decreases) if inflation expectations are lower or are better anchored (a sign of the credibility of the monetary authority).

For given financing needs, monetisation is just a leftward move along the curve.

It seems safe to assume that most advanced economies are today positioned on the right part of the curve (around point C). There is an apparent sensitivity of risk premia to any news on debt. On the other hand, inflation expectations have not yet reacted to the monetary policy impulse that results from the expansion of central banks' balance sheets.

If true, it is hard to escape the conclusion that current policies are close to optimal. In a rare moment of perfect fiscal - monetary coordination, governments are issuing bonds and central banks are buying government bonds and issuing money. Contrary to 2008–09, a large part of these purchases result in the creation of broad money in the hands of the general public (Lane 2020). Governments have the ability to lock in very low interest rates while central banks can expand their balance sheets without fear of missing their inflation objectives and mandates.

Central bank independence in the future

The government has one balance sheet, but it is managed by two actors: the fiscal and the monetary authorities. The literature has for long recognized that the control of inflation rests on the expected interaction between these two actors in the future. Which policy - fiscal or monetary – ‘dominates’ the other, ‘who moves first’, are traditional questions whose answers define the contrasting regimes of fiscal dominance and monetary dominance (Sargent and Wallace 1981).

In the post-COVID-19 environment, interactions between public debt and monetary policy will become more immediate and more intense. Fiscal and monetary authorities will have to pay greater attention to what the other is doing. There may be periods, as the one we are now going through, where close coordination will be appropriate and necessary. But conflicts may emerge in the future and the situation must be managed with that perspective in mind.

What are the consequences for central bank independence? Three remarks can be made:

- Going into the COVID-19 crisis, central bank independence was in danger of going out of fashion. In a permanently low inflation regime, its justification may not be so strong (Bernanke 2017). In addition, with many economies hitting the zero lower bound, there was an obvious need for permanent and close coordination between fiscal and monetary policies.

- Central banks will emerge from the COVID-19 crisis with balance sheets not only larger but also significantly more complex. There are many reasons why this complexity could create problems for their independence. It may drag them outside their traditional macro-economic stabilisation function. It may affect their ‘at arm's length’ modus operandi. Asset purchases have increased central banks' imprint on financial markets. Their intermediation function is more developed. Their role in credit allocation may be have become uncomfortably broader.

- At the same time, the rationale, and need, for independence has never be so strong.

In modern economies, inflation is mainly driven by expectations of future actions by the central banks. In a conventional environment, independence is meant to solve the time inconsistency problem by removing any incentive for the monetary authority to create an inflation surprise. Today, in an environment where high public debt interacts with a large monetary balance sheets, the justification for independence is more basic, even brutal: to protect the ability of the central bank to act in all circumstances.

The expectations that matter are not those relating to central banks' intentions, but those that concern the institutional environment in which they will operate. For inflation expectations to be durably stable, there must be no doubt that central banks will be in a position to raise interest rates should inflation pressures materialise, whatever fiscal (and public debt) situation exists at the time.

Fiscal dominance is never a fatality. As noted by Sargent and Wallace, "nothing in (their) analysis denies the possibility that monetary policy can permanently affect the inflation rate under a monetary regime that effectively disciplines the fiscal authority". However, when the threat of fiscal dominance is high, the institutional dimension of independence becomes very important.

In this column, I have illustrated the broad policy space that exists today. It has been created by the success in stabilising inflation expectations in the past. In the future, the permanence of that policy space, its size, its delimitations will all depend on the clarity and firmness in institutional arrangements affecting the central banks. For monetary policy – and maybe other fields as well (Wyplosz 2020) – we are entering in a period in which the quality of institutions will have a direct, and decisive, impact on the economic performance of countries.

References

Bernanke B (2017), "Monetary Policy in a New Era", Brookings Institution, 2 October.

Blanchard, O (2020), "Is there deflation or inflation in our future?", VoxEU.org, 24 April.

Blanchard, O (2019), "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates", American Economic Review 109(4): 1197–1229.

Blanchard, O and J Pisani – Ferry (2020), "Monetisation: Do Not Panic", VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Brunnermeier, M (2020), "Inflation and Deflation Pressures after the Covid Shock", scholar.princeton.edu, 12 May.

Cochrane, J H (2011), " Inflation and Debt", National Affairs.

Lane, P (2020), "Pandemic Central Banking: the monetary stance, market stabilization and liquidity", Remarks at the Institute of Monetary and Financial Stability Policy Webinar, 19 May.

Endnotes

1 https://youtu.be/H_K3dMpdqpc

2 At least for major economies; others, especially in the emerging world, may lose access to capital markets

3 Except for indexed bonds.

Sargent, T and N Wallace (1981), "Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic", Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, Fall.

Wyplosz, C (2020), "The good thing about coronavirus", in Economics in the Time of COVID-19, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.`