The Global Crisis highlighted how devastating fragilities in the residential mortgage market can be. The initial shock of an increase in mortgage arrears, due to a decline in house prices in the US and some European countries, triggered a liquidity crisis that turned into a full-blown financial crisis.1 Despite a significant contraction of the sector in the aftermath of the crisis, mortgage lending still accounts for a large share of both household debt and banks’ assets.2 Yet, given the variation in economic and financial developments, there are important differences in the depth of mortgage markets across countries. Likewise, the incidence of mortgage arrears differs considerably across countries, as well as over time for individual countries.

A better understanding of the factors that explain cross-country and within-country differences in mortgage delinquency is thus of great importance for policymakers for at least two reasons.

- First, mortgage defaults dilute the fundamentals of lending financial institutions, and amplify disruptions in financial markets.

- Second, mortgage defaults reduce households’ creditworthiness, thereby making it more difficult for them to access future financing. This may increase consumption volatility, both at the household and aggregate level, with repercussions for the real economy.

Potential causes for mortgage delinquency

The theoretical literature suggests two main explanations for mortgage arrears: ability-to-pay and strategic default (Whitley et al. 2004). According to the ability-to-pay theory of default, individuals default involuntarily when they are unable to meet current payments. The strategic default theory holds that households choose to default voluntarily after a rational analysis of all future costs and benefits associated with continuing or not continuing to meet the obligations of the mortgage. If a household faces affordability problems — which may be caused by a drop in income (for example, due to unemployment), higher mortgage payments (for example, due to higher interest rates), or a decline in house prices (leading to negative equity) — it may have no other option than to default on its mortgage obligations (Diaz-Serrano 2004, Elul et al. 2010, Demyanyk et al. 2010, Aron and Muealbauer 2016, Goodstein et al. 2017). Borrowers may default if their (potential) gains exceed the perceived costs of the expected sanctions, including access to future finance and its price (Kehoe and Levine 2001, Chatterjee et al. 2007). These costs not only depend on lenders’ willingness to inflict sanctions, but on the entire set of institutional arrangements governing the credit market, such as the rule of law, creditor rights, and bankruptcy laws (Japelli et al. 2008, Duygan-Bump and Grant 2009).

In addition to macroeconomic and institutional factors, macroprudential policies targeting the household sector may influence developments in the mortgage market. Although there is growing evidence that macroprudential policy instruments affect housing credit growth and house price increases (Galati and Moessner 2013), there is only limited evidence on whether these instruments influence the incidence of mortgage defaults (Wong et al. 2011, Gerlach-Kristen and Lyons 2015, Allen et al. 2017). Arguably, restrictive policies that discourage household leverage may strengthen financial stability over the medium term by reducing the incidence of defaults. Reduced leverage enables households to more easily absorb shocks and avoid default on mortgage payments.

Finally, mortgage market characteristics could also affect the likelihood of default. Borrowers are more likely to face difficulties in making their mortgage-related payments when interest rates are more volatile (the impact being larger for variable-rate mortgages) and/or when the periodic instalments are higher (as for loans with short maturities). Thus, the type of loan (fixed versus flexible interest rate) and loan maturity are important variables that should be taken into account when studying mortgage defaults. Another feature of the mortgage market that may be conducive to an increase in household’s leverage, and subsequently to more arrears, is the tax treatment of interest payments. Some countries give (sometimes generous) preferential treatment to mortgages (in form of deductibility of interest payments) as part of broader government interventions to encourage homeownership. Yet, in other countries such favourable tax treatment is more limited, or even non-existent. Finally, recourse legislation plays an important role in deciding for or against default. When the price of the property is less than the value of the mortgage (i.e. a household has negative equity), default is less attractive under recourse legislation as the household remains responsible for the negative equity (Ghent and Kudlyak 2011).

Empirical results

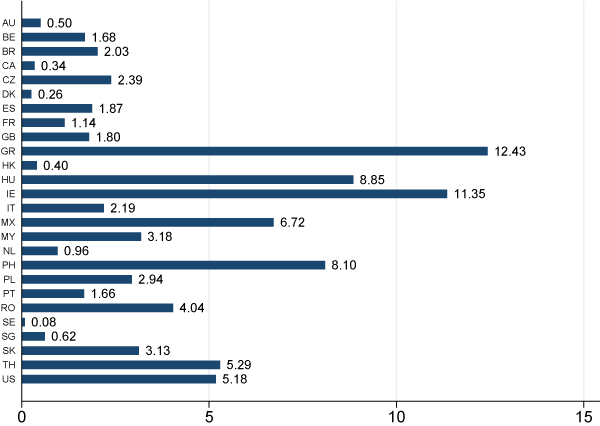

In a recent paper, we examine the incidence of mortgage arrears using a unique comparative dataset at the macro level for 26 countries from 2000 to 2014 (Stanga et al. 2017).3 To this end, we explore both the role played by various factors in explaining cross-country and within-country differences in delinquency rates, as well as the interaction between potential drivers of default. In our sample there is significant variability in annual default rates, both across and within countries. Since data on actual defaults are not available for most countries in our sample, we use the ratio of total value of mortgage arrears (over three months past due) to total value of outstanding mortgage loans as a proxy for mortgage defaults. The ratio ranges from 0.01% to 28.6% per year, with a mean of 3.2%. Average mortgage defaults over the sample period differ sharply across countries (Figure 1), ranging from below 1% in Australia, Canada, Denmark, and the Netherlands, among others, to above 8% in Greece, Hungary, Ireland, and the Philippines. There is substantial variation also within countries. Some countries have experienced significant fluctuations in the annual default rates during 2000-2014 (for example, Mexico from around 3% to a maximum of 18.5%, or Hungary from around 3% to a maximum of 14%, or the Philippines from around 3% to a maximum of 15%).

Figure 1 Average mortgage default rates per country, 2000-2014

Our findings (based on panel estimations) suggest that higher unemployment is significantly associated with an increase in mortgage defaults, while higher house prices have a strongly negative association with defaults. The intuition for the former relationship is straightforward – defaults are more likely when income shocks lead to affordability problems. For the latter, there are two potential interpretations. On the one hand, arrears increase when house prices decline, because the ability to finance consumption out of housing wealth is reduced. On the other hand, negative equity has a similar effect, as it may create incentives for strategic default. The interest spread capturing borrowers’ financial constraints (i.e. the difference between long-term government bond yield and treasury bills rate) is positively (but not statistically significantly) associated with delinquency rates.

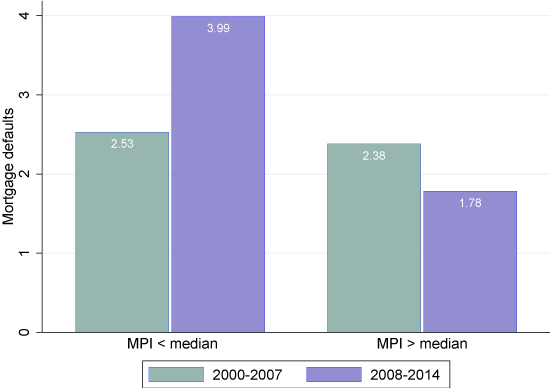

We also find that mortgage arrears are less likely under tight macroprudential policies (and in particular, loan-to-value, or LTV, ratios). Our main proxy for macroprudential regulation is the macroprudential policy index (MPI) compiled by Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey (2017). It aggregates four policy instruments – loan-to-value cap, debt service-to-income cap, capital, and provisioning requirements – that target the housing sector. The index captures changes in the intensity in the usage of prudential tools and records quarterly tightening and easing of these macroprudential instruments. Among all the instruments, LTV caps are the most commonly used. We find a significant association between the MPI and defaults – the higher the value of the index (i.e. a more restrictive lending environment), the lower the average level of mortgage defaults. This relationship seems stronger over the 2008-2014 period (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Mortgage defaults and the intensity of macroprudential policy index (MPI)

Notes: The figure plots the cross-country average mortgage default rates when MPI is below and above its median, respectively (the median is computed at the panel level). The average defaults are computed across countries in the sample for the period before and after the beginning of the financial crisis, conditional on the value of the index.

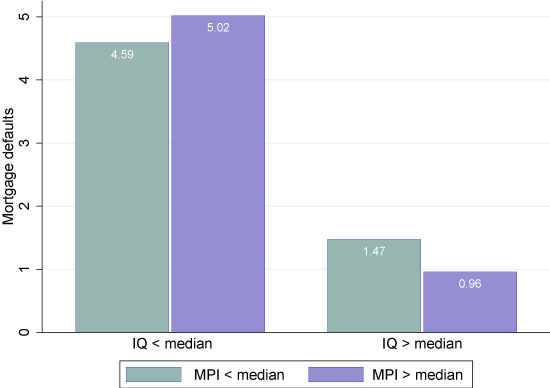

Better institutions – which improve judicial efficiency and make it easier for banks to enforce their rights – reduce the level of mortgage defaults. We consider several proxies4 for institutional arrangements and compile an index of institutional quality (IQ). We find a significant and negative relationship between IQ and mortgage arrears, both before and after the onset of the financial crisis – the higher the average quality of institutions, the lower the average mortgage default ratio (Figure 3). Moreover, the effects of macroprudential policies and institutional quality on mortgage defaults are mutually reinforcing. As illustrated in Figure 4, the effect of the MPI on defaults becomes stronger in countries with better institutions. This result suggests that the effect of tougher macroprudential policies (that reduce household leverage and ultimately deter defaults) is amplified in an institutional environment conducive to an efficient judicial system with better protection for lenders’ rights and better enforcement capabilities.

Figure 3 Mortgage defaults and institutional quality (IQ)

Notes: The figure plots the cross-country average mortgage default rates when IQ index is below and above its median, respectively. The average defaults are computed for countries in the sample with IQ larger (lower) than the median and for the period before and after the beginning of the financial crisis.

Figure 4 Mortgage defaults, MPI and IQ

Notes: The figure plots the cross-country average mortgage default rates when MPI is below and above its median, respectively. The average defaults are computed conditionally on the IQ index being below and above its median (where the medians are computed at the panel level).

We also show that the impact of mortgage market characteristics depends on macroprudential policies (or quality of institutions).

- First, we find that the interaction between the MPI and longer maturities of mortgage loans is associated with a lower incidence of mortgage arrears. The intuition for this result is that the combination of restrictive macroprudential policies (which may limit household indebtedness) and longer maturities (which make periodic mortgage payments more affordable to borrowers) is conducive to repayment.

- Second, we find evidence that in countries with predominantly fixed-interest mortgages, restrictive macroprudential policies are significantly negatively associated with mortgage arrears. Under restrictive macroprudential policies, households not only borrow less, but they are able to fix their payment obligations over a certain period of time, thus reducing the volatility of their payment obligations.

- Third, we show that in countries in which mortgage interest deductibility is permitted, restrictive macroprudential measures are (weakly) associated with lower delinquency rates.5 While most of the empirical evidence points to the relationship between mortgage interest deduction and higher house prices (or higher household leverage), our results uncover a novel effect—in the presence of restrictive borrowing constraints (i.e. stricter macroprudential policies), the tax-deductibility of the interest payments increases borrowers’ ability to pay by reducing their periodic payments.

- Finally, our results confirm a significant relationship between the degree of lender recourse on borrowers and mortgage arrears, in particular for those countries with higher institutional quality. The observed pattern points to the importance of institutional features, such as judicial efficiency and bankruptcy regulation, without which the recourse procedures per se may prove inefficient in dealing with incentives for default.

These findings suggest that dealing effectively with mortgage defaults requires a mix of policies. This should consist of both prudential regulation (with LTV caps being an important instrument in the macroprudential toolkit) and improvements in the institutional design (in particular improvements of judicial efficiency and bankruptcy regulation).

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

Akinci, O and J Olmstead-Rumsey (2017), “How effective are macroprudential policies? An empirical investigation”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, forthcoming.

Allen, J, T Grieder, B Peterson and T Roberts (2017), “The impact of macroprudential housing finance tools in Canada”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, forthcoming.

Aron, J and J Muellbauer (2016), “Modelling and forecasting mortgage delinquency and foreclosure in the UK”, Journal of Urban Economics 94: 32–53.

Chatterjee, S, D Corbae, M Nakajima and J V Rios-Rull (2007), “A quantitative theory of unsecured consumer credit with risk of default”, Econometrica 75: 1525–89.

Demyanyk, Y, R S J Koijen and O Van Hemert (2010), “Determinants and consequences of mortgage default”, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Working Paper 10‐19.

Diaz‐Serrano, L (2004), “Income volatility and residential mortgage delinquency: Evidence from 12 EU countries”, IZA, Discussion paper 1396.

Duygan‐Bump, B and C Grant (2009), “Household debt repayment behaviour: What role do institutions play?” Economic Policy 24(57): 107–140.

Elul, R, N S Souleles, S Chomsisengphet, D Glennon and R Hunt (2010), “What ‘triggers’ mortgage default?” American Economic Review 100(2): 490–494.

Galati, G and R Moessner (2013), “Macroprudential policy – A literature review”, Journal of Economic Surveys 27(5): 846–878.

Gerlach‐Kristen, P and S Lyons (2015), “Mortgage arrears in Europe: The impact of monetary and macroprudential policies”, SNB, Working paper 5/2015.

Ghent, A C and M Kudlyak (2011), “Recourse and residential mortgage default: Theory and evidence from US states”, Review of Financial Studies 24(9): 3139–3186.

Goodstein, R, P Hanouna, C D Ramirez and C W Stahel (2017), “Contagion effects in strategic mortgage defaults”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 30: 50–60.

Japelli, T, M Pagano and M di Maggio (2008), “Households’ indebtedness and financial fragility”, Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance, Working Paper 208.

Kehoe, T J and D Levine (2001), “Liquidity constrained vs debt constrained markets”, Econometrica 69: 575–98.

Stanga, I, R Vlahu and J de Haan (2017), “Mortgage arrears, regulation and institutions: Cross-country evidence”, DNB, Working paper no 580.

Whitley, J, R Windram and P Cox (2004), “An empirical model of household arrears”, Bank of England, Working paper 214.

Wong, E, T Fong, K Li and H Choi (2011), “Loan-to-value ratio as a macroprudential tool – Hong Kong SAR’s experience and cross-country evidence”, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Working paper 01/2011.

Endnotes

[1] Throughout the column we use terms ‘delinquency’, ‘arrears’, and ‘default’ interchangeably, referring to past-due payment obligations.

[2] The IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report (2017) finds that the median household debt-to-GDP ratio in advanced economies was 63% in 2016, with mortgage debt accounting for more than 50% of total household debt.

[3] Our database contains more countries and covers a longer time period than those used in previous studies (see Jappelli et al. 2008, Wong et al. 2011).

[4] The following indexes are considered—legal rights, rule of law, physical property, investor protection, creditor rights. The results are robust to the inclusion of additional indices (e.g., the number of procedures that must be followed to legally recover debt, and the time for resolving a defaulting borrower).

[5] More than half of the countries in our sample allow for some form of tax deductibility. However, the amount that can be deducted varies substantially across countries. We also examined whether tax deductibility has a direct relationship with mortgage defaults. Although our results suggest that tax deductibility increases mortgage defaults, it turned out that this result was driven by just two countries (Greece and Ireland) and we therefore conclude that it is not a robust relationship.