The EU is facing formidable challenges. The economic crisis is far from over in many Eurozone and non-Eurozone member states. The EU’s current macroeconomic and budgetary policies are not politically sustainable at the EU’s current anaemic growth rate. Less visible, but much more pernicious and damaging, is the lessening of competition in many sectors due to the past several years of crisis, a trend that is evident to varying degrees across all EU member states. This lessening of competition is slowing down EU adjustments, favours the most powerful rent-seekers, and is a sure recipe for increased inequality and political turmoil.

Since the second world war, the cure in such circumstances has always been to look at further trade liberalisation, as documented by an abundant literature (see Irwin 2009). But, this requires conceiving trade negotiations not in an isolated manner but as a support triggering and buttressing the much-needed domestic reforms.

Which are the ‘best’ preferential trade agreements for the EU?

In the absence of an increasingly unlikely Doha deal, steps toward greater trade liberalisation will rely on preferential trade agreements. This raises two questions for the EU:

- First, which preferential trade agreements are most likely to provide the biggest and fastest boost to its growth

- Second, which preferential trade agreements will best insure EU member states against the discriminatory effects of the preferential trade agreements concluded among large, non-EU economies? The latter is a key question because preferential trade agreements, by definition, favour trade between signatories to the detriment of trade between signatories and the rest of the world.

The ‘growth’ dimension

The first question focuses on the ‘growth’ dimension of trade policy. Preferential trade agreements will only be able to boost domestic growth if the economies of the EU’s preferential trade agreements partners fulfil three main conditions. They should be big enough to generate economies of scale and scope capable of having a substantial impact on the EU’s relative prices – changes in relative prices are the source of welfare gains. They should also be well regulated because modern economies are intensive in norms and dominated by services, the efficiency of which depend largely on the quality of the regulatory schemes in place. Finally, they should have a wide network of good-quality preferential trade agreements, capable of offering EU firms opportunities to access the economies already covered by those preferential trade agreements (the ‘hub’ quality) without waiting for longish negotiations with the EU.

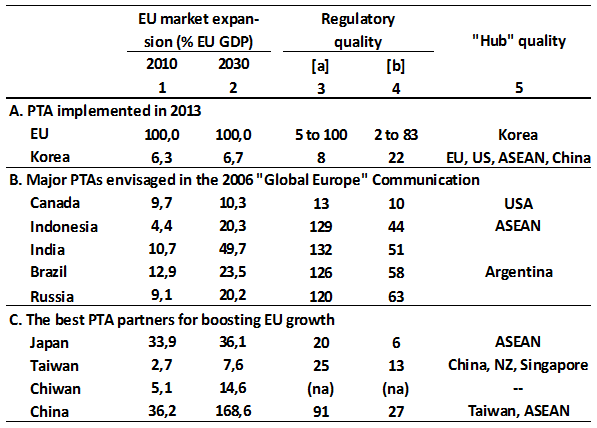

As Table 1 shows, Japan and Taiwan – apart from the US – are the only economies in the world that meet these three conditions since the EU already has a free trade agreement with South Korea. China (possibly India in the long run, but not Brazil or Russia) may offer better growth opportunities when it comes to size. But, it still scores poorly on regulatory quality, while Japan and Taiwan score better than many EU member states. When it comes to the ‘hub’ criterion, Japan has a wide network of preferential trade agreements in east Asia (a region that EU negotiators are very slow to negotiate with) while Taiwan has massive operations in China which have been recently strengthened by a key preferential trade agreement, making Taiwan a privileged hub with respect to China. The capacity of Japan and Taiwan to meet all three conditions indicates the need for a resolute EU pivot to east Asia – an outcome echoed by general equilibrium calculations (Kawasaki 2011).

Table 1. Looking for the best preferential trade agreement partners for the EU

Notes: a and b ranks of countries: the highest the country’s rank, the poorest its regulatory performance:

(a) Ease of doing business (Doing Business 2012);

(b) Overall index, Global Competitiveness Index (World Economic Forum 2011).

For the EU, only the ranks for the lowest (best) and highest (worst) EUMS are reported (note that there is no information on Malta).

Sources: Buiter and Rahbari (2011) for growth estimates and WTO Trade Profiles for the GDP of the individual countries and regions. Based on author’s calculations.

The ‘insurance’ question

The second question focuses on the ‘insurance’ dimension, which is important given the emergence of non-EU ‘mega’ preferential trade agreements around the world, such as the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership and the China–Japan–Korea initiative. These two initiatives – in particular, the Trans-Pacific Partnership which is conceived by the US as a ‘platinum’ trade agreement capable to generate deep integration among its members – can generate huge trade diversions detrimental to EU firms, especially the small and medium ones, in agriculture, several manufacturing sectors and many key infrastructure services, as documented in the paper.

Remarkably, factoring in the insurance dimension still leads to the same set of preferable preferential trade agreements for the EU: a preferential trade agreement with Japan will insure EU firms against the potential discriminatory impacts of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, while a preferential trade agreement with Taiwan will do the same with respect to the China–Japan–Korea initiative.

Balancing pivoting to east Asia and the other preferential trade agreement negotiations underway

Finally, the EU should ask itself how it should balance any pivot to east Asia with the preferential trade agreement negotiations that it already has underway. This is important when it comes to creating an order of priority for negotiations, all of which will inevitably consume a huge amount of time, staff and funds.

Regarding the US, the EU should expect difficult negotiations on an EU–US preferential trade agreement, despite the fact that the US fits well the conditions related to the ‘growth’ dimension. This is mostly because the US insists on harmonisation and/or convergence with US regulations in its Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations (as the EU was systematically doing a few years ago). As a result, the US approach to Trans-Pacific Partnership in the Pacific region seems hard to reconcile with the ‘unconditional’ mutual recognition approach that the EU will advocate in the Atlantic region – as it should also do with Japan and Taiwan. Unconditional mutual recognition is the only practical solution to different regulations among large economies, and it is consistent with the EU internal approach, as best illustrated with the EU 2006 Services Directive.

The cases of South Korea and China are quite different. They raise the problem of time consistency, since preferential trade agreements are negotiated one after the other. In both cases, the EU, Japan and Taiwan should eliminate possible negative spill-over effects on any earlier (South Korea) or future (China) negotiated trade agreements.

Finally, Brazil and India raise the issue of what to do with negotiations that are currently going nowhere. In both instances, the EU should consider abandoning the too-ambitious goal of negotiating full-fledged preferential trade agreements for the time being. It should instead focus on narrower topics with higher chances of success, such as building norms on key farm and industrial goods, and regulations in services of prime interest to both sides. This pragmatic approach is the only one that would allow building the trust among the negotiating parties which is necessary for moving further.

Conclusions

- Japan and, to a lesser extent, Taiwan are in the same situation as the EU, that is, they both need urgent domestic reforms in order to boost their economies (Japan) or to consolidate their growth (Taiwan);

As a result, the EU, Japan and Taiwan have the same profound economic interests to help each other in a difficult reform process.

- Such negotiations can last a long time since they deal with complex matters.

Is this a problem? Not if negotiations are used well. For instance, the mutual evaluation of their respective regulations during the negotiations (a process necessary for granting unconditional mutual recognition) will rapidly reveal to each partner the strengths and the weaknesses of its current domestic regulations (and of its partner), hence the reforms to be done. If the partners take the necessary actions swiftly, markets will recognise the benefits of the agreement before its final signature.

References

Buiter, Willem and Ebrahim Rahbari (2011), “Trade transformed –The emerging corridors if trade power”, CITI Global Perspective Solutions (GPS), CITI, 18 October.

Irwin, Douglas A (2009), Free trade under fire, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Kawasaki, Kenichi (2011), “Impact of Trade Liberalization: Economic Model Simulations”, conference on the Future of the Japan-EU Free Trade Area, Keio University, 29 October.

Messerlin, Patrick (2012), “The Much Needed EU Pivoting to East Asia”, AsiaPacific Journal of EU Studies 10(2), 1-18.