Recent decades have witnessed an explosion in the activities of multinational corporations. Sharp declines in trade and telecommunication costs have led to increasing separation of management and production facilities within individual firms. The rise of multinational firms represents a particularly extreme example of expanding geographic distance between firm leadership and production. Firms that agglomerated in Silicon Valley and Detroit now have subsidiaries clustering in Bangalore (termed the Silicon Valley of India) and Slovakia (nicknamed Detroit of the East).

Since Marshall (1920), economists have recognised the importance of agglomeration benefits and argued that the industrial clusters we observe (e.g., Silicon Valley) can be explained by the cost and productivity advantages firms enjoy when they locate near one another. These advantages include:

- Proximity to suppliers and customers

Transportation costs induce plants to locate close to their inputs and customers and determine the optimal trading distance between suppliers and buyers. This effect can be especially strong for multinational firms given their large volumes of sales and intermediate inputs.

- External scale economy in factor markets

Firms' proximity to each another shields workers from the vicissitudes of firm-specific shocks and offers workers incentives to accept lower wages. Externalities also occur as workers move from one job to another; this is especially true between multinational firms given their similar skill requirements and business culture. External scale economies in the capital market can also lead to agglomeration, particularly for the many multinational firms involved in capital-intensive activities. Geographically concentrated industries offer better support to providers of capital goods (such as producers of specialised components and providers of machinery maintenance). They also reduce the risk of investment (due, for example, to the existence of resale markets).

Knowledge spillovers also provide an important agglomeration incentive, especially to multinational firms given their involvement in advanced technologies and R&D activities.

Existing evidence

A number of studies in international trade including Head, Ries, and Swenson (1995), Head and Mayer (2004), Blonigen, Ellis, and Fausten (2005), and Amiti and Javorcik (2008) have examined the agglomeration of multinational firms with vertical production linkages in countries and regions such as EU, US, and China. The results of these studies suggest that multinational firms with stronger linkages are more likely to invest in the same location.

While these findings shed important light on the role of vertical production relationships in firms’ agglomeration decision within a given country, much remains unknown about the global networks of multinational firms, how they compare to the traditional autarkic industrial landscape, and the effect of other agglomeration benefits. Do multinationals colocate with one another worldwide? Do they agglomerate in the same fashion as domestic firms? Finally, are there hub-and-spoke corporations? An answer to these questions is central to the long standing debate over the consequences of foreign direct investment (FDI), and plays a critical role in the makings of FDI policy.

In recent research, we address these questions by constructing a topology of multinationals’ networks and examining the significance and causes of multinational co-agglomeration (Alfaro and Chen, 2009). Our results indicate significant evidence of multinational firms’ co-agglomeration, driven by factor-market externalities, knowledge spillovers, and vertical production linkages. The importance of these factors differs across headquarters, subsidiary, and employment networks, but knowledge spillovers and capital-market externalities, two traditionally under-emphasised forces, exert consistently strong effects. We also record considerable heterogeneity in the extent of agglomeration across multinational subsidiaries and find that multinationals are far from equal within the network.

Measuring agglomeration

As Head and Mayer (2004) note, measuring spatial concentration of activity is a far less trivial exercise than it might seem at first. Analyses in this area face two main challenges. First, most existing indices of agglomeration depend on the level of geographic aggregation and do not fully account for spatial continuity. Second, the majority of existing studies are constrained by data availability and focus on agglomeration within a country or a region.

In our research, we investigate the locational interdependence of multinationals in a global and continuous metric space. We construct indices of network density based on a new empirical methodology from urban economics introduced by Duranton and Overman (2005). These indices measure both the statistical significance and extent of agglomeration at a given threshold distance. They exhibit distinct advantages over traditional measures of agglomeration, including the independence of the scale and aggregation of geographic units and controlling for the overall distribution of multinationals.

The construction of agglomeration measures is further facilitated in our research by the use of a new worldwide establishment dataset, WorldBase compiled by Dun and Bradstreet. This dataset includes nearly the world population of multinationals, enabling us to go beyond the study of individual countries and examine the topology of global multinational networks. Moreover, the dataset reports the physical address and postal code of each establishment (while most existing firm-level datasets report business registration addresses). The latter information allows us to obtain geocode information for each establishment to construct a true index of agglomeration using continuous metrics of space.

Patterns of multinationals networks

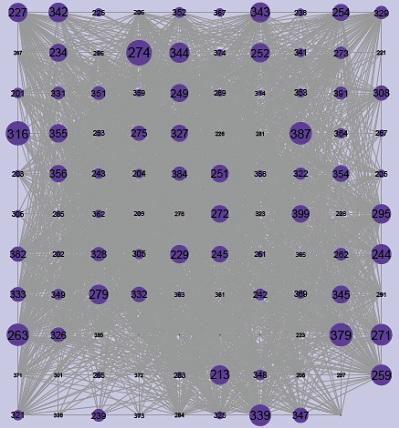

Figure 1 plots the network of multinational headquarters, wherein each node represents an SIC 3-digit manufacturing industry and each link indicates the existence of a positive network density between two industries at the 200km level (i.e., statistically significant co-agglomeration within 200km). We use the size of each node to represent the number of agglomerative links, i.e., the number of industries that agglomerate with a given sector at 200km. Industries represented by larger nodes are the centre of the multinational network. It is clear that not all industries are equal. Some, such as Paperboard Mills (263), Newspaper Publishing, Publishing and Printing (271), Miscellaneous Publishing (274), Leather Products Luggage (316), Miscellaneous Primary Metal Products (339), Miscellaneous Transportation Equipment (379), and Watches, Clocks, Clockwork Operated Devices and Parts (387), attract more co-agglomeration than others.

Figure 1. The network of multinational headquarters

Notes: Each node represents an SIC 3-digit manufacturing industry. Industries in which there is significant co-agglomeration of multinational headquarters at 200km are linked. The size of each node is proportional to the number of co-agglomerating industries.

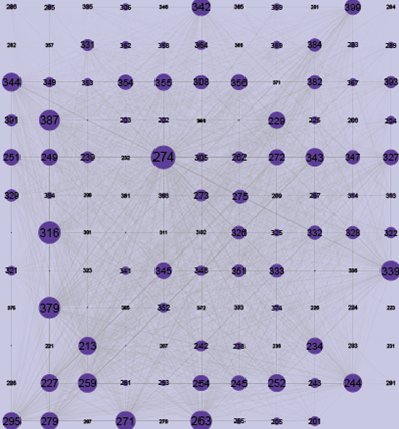

This observation is true as well for the network of multinational subsidiaries in Figure 2. The centrality of industries varies considerably. The degree of co-agglomeration is, however, substantially lower, suggesting that the multinationals’ subsidiary networks are more dispersed around the world than their headquarters counterparts.

Figure 2. The network of multinational subsidiaries

Notes: Each node represents an SIC 3-digit manufacturing industry. Industries in which there is significant co-agglomeration of multinational subsidiaries at 200km are linked. The size of each node is proportional to the number of co-agglomerating industries.

Why do multinationals agglomerate? Findings and implications

Our research suggests that the role of agglomeration economies differs among the different types of networks. All agglomeration economies except input-output linkages (namely, knowledge spillovers and capital- and labour-market externalities) exert a significant effect on the co-agglomeration of multinational headquarters, whereas in the case of subsidiary co-agglomeration all factors but labour-market externalities play a significant role. Capital-market externalities, in particular, pose a strong effect in the subsidiary network. The driving forces in the multinational subsidiary-employment network are knowledge spillovers and labour-market externalities, factors that require high labour mobility and close labour interaction.

These results differ from the findings of existing urban economics studies that focus on domestic agglomeration. A recent study by Ellison, Glaeser, and Kerr (2009) finds that input-output relationships have the largest effect in explaining the agglomeration of US manufacturing firms. Intellectual spillovers, in contrast, play a weaker role. Our research shows that factor-market externalities and knowledge spillovers exert the largest impact on multinational headquarters and subsidiary agglomeration, whereas input-output linkages only play a significant role among subsidiaries. These differences suggest that, with the geographic separation of headquarters services and production activities, the determinants of multinational location differ from those of average manufacturing firms. The results further highlight the importance of distinguishing the structure of multinational networks from that of traditional industrial production.

Multinationals are also far from equal within each pair-wise industry network. There is considerable heterogeneity in the extent of agglomeration across multinational subsidiaries. Subsidiaries with greater revenue or employment and higher productivity tend to become the hubs of networks; smaller, less productive subsidiaries emerge as spokes.

Our findings suggest that more policy consideration should be given to the interdependence of multinational firms. This interdependence goes beyond vertical production linkages; it can arise as a result of externalities in knowledge, physical capital, and labour markets. These externalities can not only exacerbate the outward and inward movement of multinationals, but also magnify the effects of FDI in home and host countries on, for example, factor markets and technology spillovers. Although the realisation of Marshallian externalities is a complex process, a preferential policy scheme in which incentives are offered first to industries with the greatest positive spillovers could be more effective than a uniform incentive system.

References

Alfaro, Laura and Maggie Chen (2009). “The Global Networks of Multinational Firms”, NBER Working Paper 15576.

Amiti, Mary and Beata Smarzynska Javorcik (2008). “Trade costs and location of foreign firms in China”, Journal of Development Economics 85(1-2): 129-149.

Blonigen, Bruce A., Christopher J. Ellis, and Dietrich Fausten (2005). “Industrial Groupings and Foreign Direct Investment”, Journal of International Economics 65(1): 75-91.

Duranton, Gilles and Henry Overman (2005). “Testing for Localization Using MicroGeographic Data”, Review of Economic Studies 72(4): 1077-1106.

Ellison, Glenn, Edward Glaeser, and William Kerr (2009). “What Causes Industry Agglomeration? Evidence from Coagglomeration Patterns”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Head, Keith, John Ries, and Deborah Swenson (1995). “Agglomeration Benefits and Location Choice: Evidence from Japanese Manufacturing Investments in the US”, Journal of International Economics 38(3-4): 223-247.

Head, Keith and Thierry Mayer (2004). “The Empirics of Agglomeration and Trade” in Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, Volume 4. Edited by J. V Henderson and J.E Thisse. Elsevier: 2609-2669.

Marshall, Alfred (1920). Principles of Economics. London, UK: MacMillan and Co.