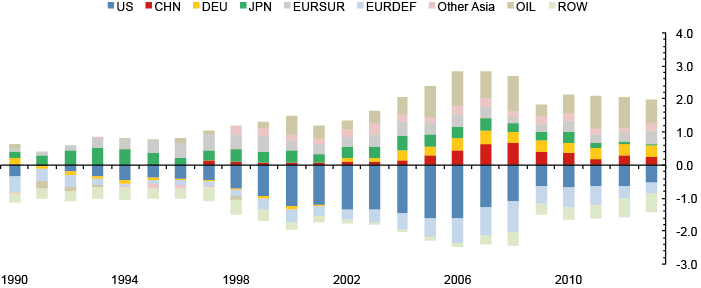

Global current-account (‘flow’) imbalances reached historical high levels in 2006 (see Figure 1). At that time, academics and policymakers were concerned about the systemic risks associated with these imbalances. In particular, they were worried that countries with large deficits and growing external liabilities – most notably the US – might suffer an abrupt loss of confidence and financing, leading to massive disruptions in the global financial system and the world economy.

Figure 1. Global current-account imbalances (% of GDP)

Source: IMF staff calculations

Note: Oil exporters = Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bolivia, Brunei, Darussalam, Chad, Republic of Congo, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Norway, Oman, Qatar, Russia, SaudiArabia, South Sudan, Timor-Leste, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Yemen; Other Asia = Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan Province of China, Thailand. European economies (excluding Germany and Norway) are sorted into surplus or deficit each year by the signs (positive or negative, respectively) of their current-account balances.

Narrowing flow imbalances

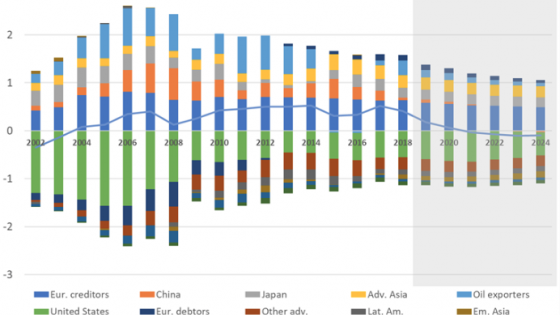

Eight year later, global flow imbalances have shrunk by over one third, changing their composition along the way. The imbalances of the top ten deficit economies dropped by nearly half (as a % of world GDP) and those of the top ten surplus economies dropped by one fourth. Moreover, the imbalances that used to be the main concern in the mid-2000s – the large deficit in the US and the surpluses in China and Japan – have more than halved. But some surpluses, especially those in some European economies and oil exporters, remain large and the current-account balances in some advanced commodity exporters and major emerging market economies have deteriorated. At the same time, large European deficits have undergone painful external adjustment. Lastly, the concentration of these flow global imbalances, particularly deficits, fell dramatically.

As a result of these changes, the configuration of global flow imbalances in 2013 looks less troublesome than that in 2006. In particular, the systemic risks associated with global current-account imbalances have surely decreased but not disappeared. These developments raise two important, interrelated questions:

- How durable is the recent narrowing of imbalances?

- How concerned should we be about the new current configuration of imbalances?

To shed light on these two questions, we need to examine the mechanics of the recent current-account adjustment and how net debtor and creditor positions (‘stock’ imbalances) have been affected by this adjustment (see IMF 2014a for more details).

The mechanics of the flow adjustment

In theory, there are two main drivers of current-account adjustment:

- Changes in aggregate expenditure (‘expenditure changing’); and

- Changes in the composition of this expenditure between foreign and domestic goods and services (‘expenditure switching’).

The former operates through movements in an economy’s domestic demand vis-à-vis that of its trading partners while the latter operates mainly through movements in an economy’s real exchange rate. Importantly, the composition of these mechanisms has implications for both external (current-account) and internal balances (unemployment and output gaps).

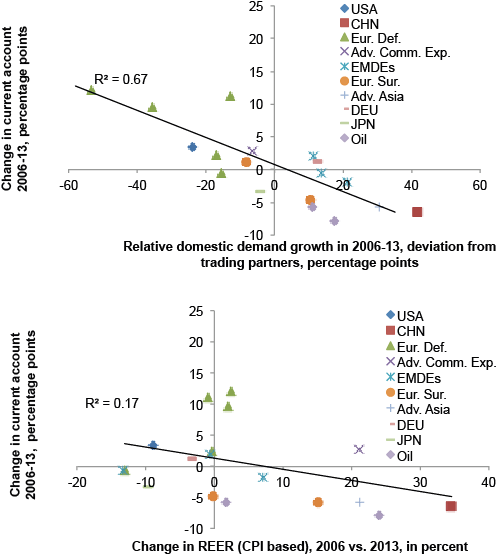

We find that much of the recent narrowing in flow imbalances was driven by expenditure reduction in deficit economies after the Global Crisis (Figure 2; see also Lane and Milesi-Ferretti 2014). This, in turn, resulted in a significant import compression and improvement in the current-account in these economies. In contrast, movements in real exchange rates played a more limited role in the recent narrowing of imbalances, with few exceptions (China and the US being two important ones). Factors that might have acted against higher exchange rate realignment include changes in investor sentiment (flows to safe havens after the crisis) and the fact that the Eurozone’s economic and monetary union includes both large surplus and large deficit economies.

Figure 2. The mechanics of adjustment: Expenditure reduction versus expenditure switching

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: Advanced commodity exporters = Australia; Advanced Asia = Singapore; Emerging market and developing economies = Poland, South Africa, Turkey; Europe deficit = Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom; Europe surplus = Netherlands, Switzerland; Oil exporters = Norway, Russia.

This means that the recent external adjustment process has entailed high economic costs in many economies – most notably, high rates of unemployment and output gaps. But, as activity recovers and output gaps start to close in deficit economies, current-account imbalances are likely to widen once again. This raises the question of how durable the narrowing in flow imbalances is likely to be.

The answer to this question depends on whether the narrowing in imbalances has been cyclical or structural. Of course, the uncertainty about magnitudes of output gaps, most notably in the Eurozone, complicates the task of separating cyclical from structural adjustment. This notwithstanding, the evidence suggests that most of the adjustment has been structural. This is so since the estimated cyclical component in global imbalances is small, reflecting a cross-country synchronicity in output gaps and their relatively small estimated size.

Widening stock imbalances

Net creditor and debtor positions have diverged further thanks to reduced, but not reversed, current-account surpluses and deficits. Persistently high ratios of net external liabilities to GDP in some advanced deficit economies also reflect the low nominal output growth. Comparing the top ten debtor economies and top ten creditor lists in 2006 and 2013 reveals striking inertia in these rankings and significant overlap with the top-ten list for flow imbalances. Over the past eight years, stock imbalances have become, if anything, slightly more concentrated on the debtor side.

Where are global imbalances headed?

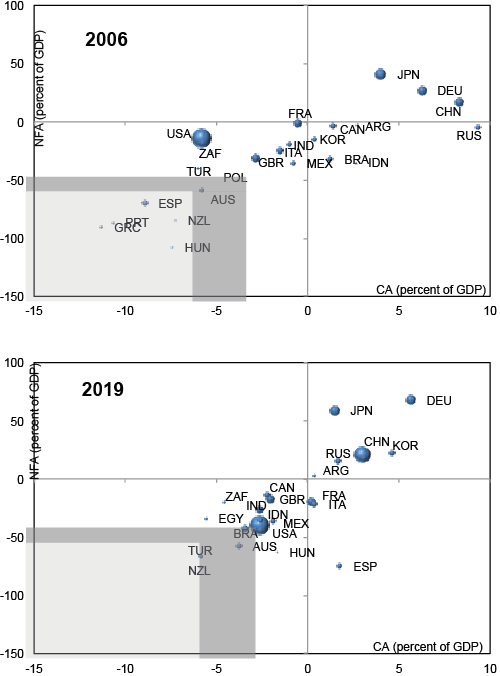

Baseline projections underlying the World Economic Outlook suggest a further narrowing of flow imbalances together with an estimated further widening of stock imbalances. Under these projections, the evolution of current-account balances and net foreign asset positions suggests a reduction in external vulnerabilities in the coming years (Figure 3).

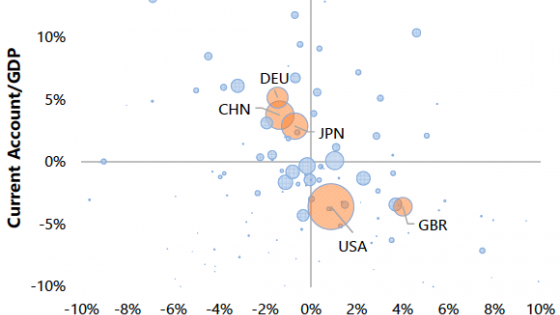

Figure 3. Vulnerabilities to the global economy: Current-account and net foreign assets, 2006 and 2019

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: Size of bubbles is proportional to the share of World GDP. Shaded areas represent vulnerability thresholds for advanced economies (light gray) and emerging market and developing economies (dark and light gray).

Nevertheless, some current-account deficits and surpluses, while smaller, are still excessive relative to levels consistent with fundamentals and desirable policy settings (see, for instance, IMF 2014b). Moreover, several economies, including a few emerging market economies, remain vulnerable to shifts in market sentiment or to sudden increases in interest rates. In addition to the systematically large debtors, several smaller European economies and some frontier market economies remain vulnerable over the medium term.

To mitigate these vulnerabilities, debtor economies will ultimately need to improve their current-account balances and strengthen their growth performance. Stronger external demand and more expenditure switching would help on both accounts. Policy measures to achieve stronger and more balanced growth in the major economies, including in large surplus economies, will also be beneficial.

Conclusion

Global current-account imbalances have narrowed substantially since their peak in 2006 and much of the narrowing is likely to be durable. While concerns about flow imbalances have lessened, risks remain with respect to stock imbalances. Some large debtor economies remain vulnerable to changes in market sentiment or to sudden increases in interest rates representing continued possible systemic risk. Containing remaining imbalances requires a rebalance in global demand.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References:

International Monetary Fund (2014a), “Are Global Imbalances at a Turning Point?”, World Economic Outlook, Chapter 4.

International Monetary Fund (2014b), “2014 Pilot External Sector Report,” IMF Multilateral Policy Issue Report.

Lane, P and G M Milesi-Ferreti (2014), “Global Imbalances and External Adjustment after the Crisis.” IMF Working Paper 14/151.