People hold strong views about gentrification. Many are certain that it displaces poor families and upends their lives. Yet, while research clearly shows that gentrification is growing more prevalent, at least in the US (Couture and Handbury 2019, Baum-Snow and Hartley 2017, Ellen and Ding 2016), there has been little evidence to date on how gentrification actually affects children’s health and wellbeing. Our studies use a previously untapped data source to shed new light on these impacts in New York City, a city that has experienced dramatic gentrification in many neighbourhoods (Dragan et al. 2019a, 2019b). The existing, though sparse, research on gentrification focuses on the more limited question of whether gentrification accelerated displacement. Our studies shed light on this question too.

We rely on New York State Medicaid claims data, which cover the near universe of poor and near-poor children in New York City and allow us to track residential moves and health outcomes for a cohort of low-income children born between 2006 and 2008. Importantly, we are also able to focus on the set of children who live in market-rate rental housing and are presumably most vulnerable to displacement.

Does gentrification cause displacement?

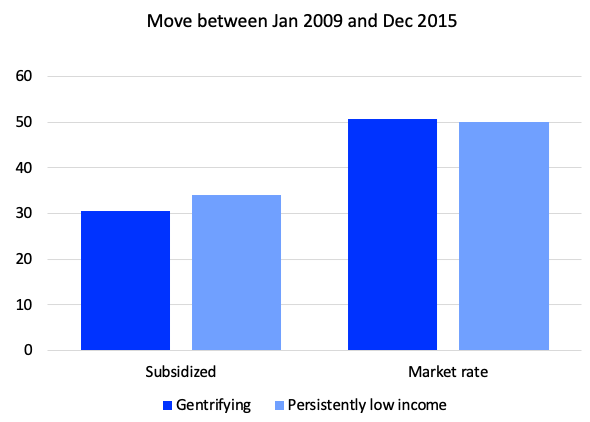

Our first study suggests that low-income children who start out in low-income neighbourhoods that later gentrify (or that experience top-decile growth in the share of college-educated residents) are no more likely to move over the seven-year follow-up period than those who start out in neighbourhoods that remain low-income and do not gentrify (Dragan et al. 2019a). While low-income children in market-rate rentals move often, they do not move any more often from gentrifying neighbourhoods (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Regression-adjusted mobility rates in rapidly gentrifying and persistently low socioeconomic status tracts

Further, we find that the average low-income child who starts out in an area that later gentrifies experiences a reduction in neighbourhood poverty. Specifically, low-income children who in 2009 live in low-income areas that later gentrify experience a roughly 3 percentage point greater decline in neighbourhood poverty than those who start out in low-income areas that do not gentrify.

While these reductions are driven by the stayers, families moving from gentrifying neighbourhoods do not end up in more disadvantaged areas than those who move from persistently low socioeconomic status neighbourhoods, though they do travel further when they move. Contrary to conventional wisdom, movers from gentrifying neighbourhoods end up in areas with similar poverty rates, and if anything, lower levels of crime. Our core results hold up to multiple measures of gentrification.

We are frequently asked why gentrification does not cause more displacement. It is possible that gentrifiers move into vacant or newly constructed homes and thus put less pressure on rents. Many neighbourhoods that gentrify start out with fairly high vacancy rates, as they have often experienced depopulation. Further, some low-income renters live in subsidised housing that is shielded from market forces, particularly in New York City where a relatively large share of the rental housing stock is regulated or subsidised. Moreover, even the private, unsubsidised housing stock within neighbourhoods may be segmented. Original low-income renters may live in buildings that are not as attractive to in-movers and thus do not experience the same increases in rent.

Perhaps most importantly, our results do not suggest that displacement doesn’t occur in gentrifying neighbourhoods; they simply suggest that rates are no higher in those neighbourhoods than in non-gentrifying ones. Low-income households tend to live in unstable housing conditions and move frequently in all types of neighbourhoods, even those showing no signs of gentrification.

Our results also do not deny the fact that neighbourhoods are changing. They are. It’s just that the changes are driven more by who moves into the neighbourhood than by who moves out.

And importantly, gentrification may affect the health and wellbeing of families and children even if they don’t experience the higher rates of displacement that many assume. Gentrification is disruptive. It brings new, often culturally different, residents to a neighbourhood; it generates changes in neighbourhood conditions that may increase the cost of living and raise rents for sitting tenants. These changes could potentially heighten anxiety and discomfort even without elevated rates of displacement.

Of course, some of the changes that gentrification brings to low-income areas might enhance health, such as increased safety, improved parks, and new businesses and economic opportunities. To the extent that they can stay in their homes and communities, low-income residents may benefit from these new investments and opportunities.

Gentrification and children’s health

Despite these potential pathways, we know very little about how growing up in a gentrifying neighbourhood affects children’s health. To help fill this gap, our second paper uses New York State Medicaid claims data to examine health outcomes (Dragan et al. 2019b). Specifically, we again track a cohort of low-income children born in the period 2006–2008 through ages 9–11. We compare health outcomes of those who started off in areas that then gentrified between 2009 and 2015 with similar children who started off in observationally equivalent low-income neighbourhoods that saw little economic change in subsequent years.

We see no evidence that gentrification affects their health-system utilisation or rates of asthma or obesity when they are assessed at ages 9–11 (Figure 2). Gentrification is, however, associated with moderate increases in diagnoses of anxiety or depression, at least among those living in market-rate housing. Anxiety and depression are rare diagnoses among children 9–11, so these increases, from very low baseline levels, are small in absolute terms. Yet they merit continued investigation as this cohort continues to age into later adolescence, when these conditions generally become more prevalent.

Figure 2 Percent of children diagnosed with selected diseases and receiving well-child visits among children ages 9–11 in 2015–17, by baseline neighbourhood

Concluding remarks

In summary, our papers show that gentrification does not appear to bring the extreme changes that either critics or defenders of the phenomenon assume. Our research provides new evidence that, at least in New York City, children growing up in gentrifying neighbourhoods are no more likely to leave their neighbourhoods and when they move, they do not end up in more disadvantaged areas. On net, children born into gentrifying areas end up living in lower-poverty areas on average. Further, we see little evidence that gentrification dramatically alters the health status or health-system utilisation of children by age 9–11.

Still, gentrification can bring unwelcome changes too. It may raise living costs for many original residents and make them feel like they no longer belong. This may explain the somewhat elevated levels of anxiety and depression we find for children growing up in gentrifying areas. But the effects of gentrification appear to be far more nuanced than typically believed.

From a policy perspective, our research shows that low-income families living in subsidised housing are more likely than their peers in market-rate housing to remain in gentrifying neighbourhoods as they change and less likely to experience elevated rates of anxiety and depression as they live through those changes. Our research also suggests the potential value of efforts in gentrifying neighbourhoods to ensure that all residents feel part of the community and can take advantage of any new opportunities.

References

Baum-Snow, N, and D Hartley (2017), “Accounting for central neighborhood change, 1980–2010”, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Working Paper 2016–09.

Couture, V, and J Handbury (2019), “Urban revival in America: 2000–2010", NBER Working Paper 24084.

Dragan, K, I G Ellen and S Glied (2019a), “Does gentrification displace poor children? New evidence from New York City Medicaid data”, NBER Working Paper 25809.

Dragan, K, I G Ellen and S Glied (2019b), “Gentrification and the health of low-income children in New York City”, Health Affairs 38(9): 1425–1432.

Ellen, I G, and L Ding (2016), “Gentrification: Advancing our understanding of gentrification”, Cityscape 18(3): 3–8.