Researchers hope to understand yield curve movements, at least at times when they should be driven by macroeconomic news, such as Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announcements or the release of the US employment report. But so far, even in these event windows, an explanation of most of the variance of yields has eluded scholars. We argue that news does indeed explain nearly all yield curve changes in event windows, but we have not been looking in the right place.

This is because only part of the news is observable to econometricians – the part for which surveys exist, which means that surprises can be measured. But any news release has many dimensions and markets respond to all of them. Un-surveyed news is unobservable to an econometrician and shows up as the unexplained residual in econometric work. We document this and propose a method for estimating the unobserved news as well.

Only unexpected releases – surprises – should affect asset prices, as expectations are already priced in. For macroeconomic data releases, long time series of market consensus expectations of releases are available. Since, by definition, these surprises have no autocorrelation, simple OLS regression of changes in yields at any maturity on the surprises lets us estimate the effect of that news on yields.

These regressions have been run by Fleming and Remolona (1997), Altavilla et al. (2017) and Gilbert et al. (2017) among others. All find strong and statistically significant effects of news on yields. However, even in tight intraday windows of 30 minutes around the releases, the R-squared values of these regressions never exceed 40% and are usually much lower. Hence, most yield curve changes are unexplained, even close to news announcements.

Identification via heteroskedasticity

Rigobon and Sack (2006) – using the elegant methodology developed by Rigobon (2003) – argue that surprises are measured with error because the surveys do not adequately capture expectations. In this case, the coefficients would be affected by classical measurement error and would be biased towards zero, and the R-squared values would naturally also be smaller. Their alternative estimate notes that OLS uses information only from the announcement windows. But comparing the covariance matrix of asset price changes around announcement windows with the covariance matrix of asset price changes at the same time on days without announcements can identify the effect of news on yields. The identifying assumption is that only the variance of news changes between the two windows. Hence this method is called identification via heteroskedasticity.

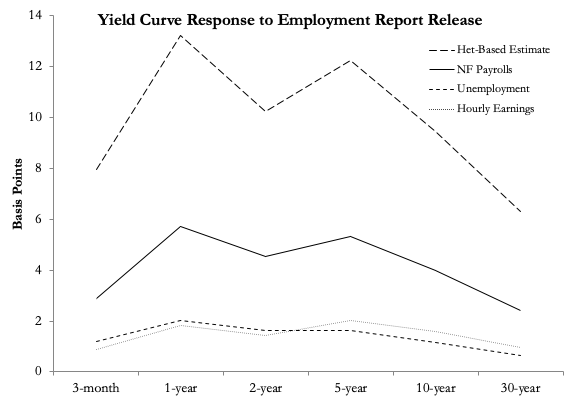

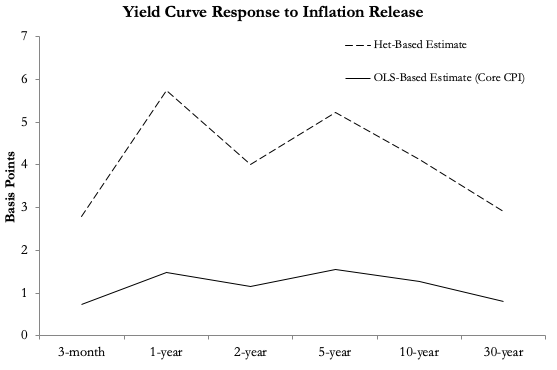

Figure 1 shows the OLS-based estimates of the effects of nonfarm payrolls, unemployment, average hourly earnings and core CPI surprises, with the heteroskedasticity-based estimates of the effects of these releases. Heteroskedasticity-based identification finds larger effects of news on yields, supporting the measurement-error-in-surveys interpretation that Rigobon and Sack (2006) put forward. In this approach, OLS- and heteroskedasticity-based estimates are seen and used as substitutes. Researchers either use one method or the other.

Figure 1 OLS- and heteroskedasticity-based estimates of the yield curve response to news

Source: Gürkaynak et al. (2018).

We argue that these methods capture fundamentally different aspects of the relationship between news and asset prices (Gürkaynak et al. 2018). The key insight is that news is multidimensional. The FOMC announces a policy decision and releases a statement. The statement itself elicits a market response (Gürkaynak et al. 2005). Likewise, the nonfarm payrolls release is part of the employment report, and that report has about 40 pages of numbers, many of which elicit a meaningful market response. Although we can measure the surprise in the policy action or the non-farm payrolls release, other dimensions of the news are unobservable to the econometrician, as there are no surveys for them. Such latent news will affect the heteroskedasticity-based estimator, which conditions on the time of the release, but not the OLS estimator, as that conditions on the size of the headline surprise.

Thus, these two estimators capture different effects. OLS focuses on the effect of the headline surprise, while the heteroskedasticity-based estimator captures the effect of the release as a whole.

Naturally, this leads to using these two methods together as complements, to separate the news effects of the headline (observable) surprises, from those of the latent (unobservable to the econometrician) surprises. We propose an efficient one-step estimator to do this. We have made a user-friendly code to implement the estimator available to researchers.

With our estimator we can determine how many latent news factors would be needed to capture the yield curve response to macroeconomic announcements. The answer: just one! And not one per release, but one across all releases.

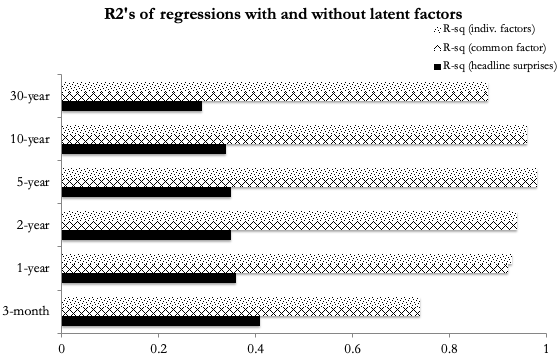

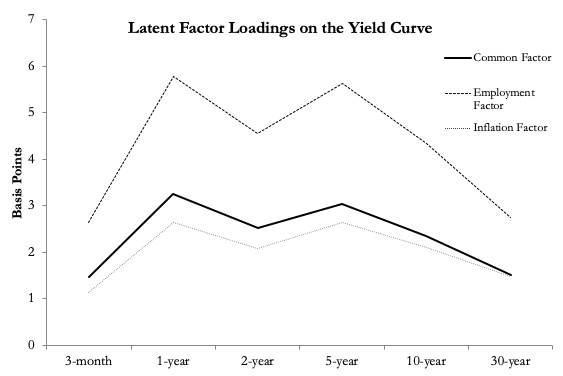

The same latent factor that captures the unobserved GDP release news also captures the unobserved PPI news, and all other releases. With one latent factor included, the R-squared of regressions is greater than 90%. At first sight this seems impossible. But it begins to make sense when one first verifies that the R-squared is the same when one latent factor per release is included (Figure 2, left-hand panel), and also that, across the yield curve maturities, every one of these latent factors has the same factor loadings (up to scale), as shown in the right-hand panel of Figure 2. Hence, combining them into one latent factor does no harm. In fact, headline (observable) news also elicits the same shape of responses from the yield curve (the OLS responses in Figure 1).

Figure 2 The effect of including one latent news factor

Source: Gürkaynak et al. (2018).

We perform various checks to verify that the latent factor that we extract indeed captures non-headline news. We can show, for example, that when we do not include the nonfarm payrolls surprise in the set of observables for employment report days, the latent factor closely tracks it. We also show that the latent factor for the FOMC announcements is consistent with the financial press writeup of these statements. Well-known surprises in the statements show up as large readings of the latent factor.

What does this mean?

It means, first of all, that news explains more or less all of the yield curve changes in event windows. By conditioning only on the news that we can observe – the headline news – we were leaving out an important source of variation. Including the non-surveyed news as a latent factor corrects this problem and uncovers the true, almost perfect relationship between news and yield curve changes in news-release windows.

It also means that we should work to understand the economics behind the common response of the yield curve to news. This is a level-like response with a hump at about the two-year maturity. The resemblance to a VAR impulse-response is obvious, and important to understand. Mechanically, a combination of monetary policy inertia, changing beliefs about long-run inflation and real rates, and changes in term premia must underlie the change in the yield curve. The next task is to relate these to news. Now that we properly understand whatmoves the yield curve, at least in news release windows, we can focus on whyit elicits that response.

References

Altavilla, C, D Giannone, and M Modugno (2017), “Low frequency effects of macroeconomic news on government bond yields", Journal of Monetary Economics 92: 31-46.

Gilbert, T, C Scotti, G Strasser, and C Vega (2017), “Is the intrinsic value of a macroeconomic news announcement related to its asset price impact?", Journal of Monetary Economics 92: 78-95.

Gürkaynak, R S, B Kısacıkoğlu, and J H Wright (2018), “Missing Events in Event Studies: Identifying the Effects of Partially-Measured News Surprises”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13153.

Gürkaynak, R S, B Sack, and E T Swanson (2005), “Do Actions Speak Louder than Words? The Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements", International Journal of Central Banking 1: 55-93.

Fleming, M J and E M Remolona (1997), "What Moves the Bond Market?", Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review 3: 31–50.

Rigobon, R (2003), “Identification through Heteroskedasticity," Review of Economics and Statistics 85: 777-792.

Rigobon, R and B Sack (2006), “Noisy Macroeconomic Announcements Monetary Policy and Asset Prices", in John Y Campbell (ed.), Asset Prices and Monetary Policy, University of Chicago Press.