The ongoing Covid-19 crisis has the potential to change the institutional design of the European Union (EU). While the epidemic has hit all member states, the incidence and economic consequences have been quite different across countries. For instance, Italy was affected much more than Germany, when the economic recovery in Italy was already modest and the fiscal situation bore the burden of past policies.

In response to these challenges, the European Council has just approved an ambitious recovery plan that contains elements of both common debt issuance and large-scale transfers. The Council agreement reviewed the proposal made by the European Commission, cut down the amount of transfers in favour of more loans, and modified the governance of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, introducing an ‘emergency brake’ for approving the fulfilment of milestones and targets of Member States’ recovery plans. However, the Commission’s Next Generation EU (NG-EU) plan contains very innovative instruments, and even though it is meant to be temporary, it could represent a step towards reforming Europe’s institutional set-up that has long been described in the literature as ‘incomplete’ (e.g. Spolaore 2016, Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2020).

For instance, the European Banking Union is still half-built and so far, the euro area has lacked macroeconomic stabilization instruments to accompany their common monetary policy. These very instruments could insure euro area member states against large asymmetric shocks. The debate on EU own tax resources, crucial also for the Recovery Fund, is far from over (Bordignon and Tabellini 2020). The Stability and Growth Pact is criticized from all sides (European Fiscal Board 2019) and the euro area still lacks a credible approach to sovereign debt restructuring. These issues are forcefully coming back with the pandemic and an overall reform process might emerge.

In many instances, ideological differences and heterogeneous views across countries have led to the blocking, the delay or an only partial implementation of reforms in the past (Alesina et al. 2017). The NG-EU itself has been approved only after a long debate. At the same time, it is generally accepted that a reform process is urgently needed (Guiso et al. 2019).

On what grounds and on which policy issues could change be implemented?

In a recent paper, we look for answers to this question by using data from an original survey conducted in late 2018 with the members of the national parliaments in three large European countries: France, Germany and Italy (Blesse et al. 2020). The survey questions address a broad range of reform issues and cover fiscal and monetary policies as well as EU governance mechanisms.

The survey allows us to gain insights into several different issues. First, we analyse the determinants of the opinions of members of national parliaments on EU and euro area reform issues. A first result is that party membership (and the relative alliances in the EU parliament) is quantitatively more important than nationality in determining these views. Results of national parliamentary elections could thus change the political feasibility of reforms.

Our second insight speaks to particular policy and institutional reform areas. For the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) area, Italian members of parliament on average strongly support a deepening of the EMU project by setting up new or strengthening existing institutions like a European Unemployment Insurance (EUI), Eurobonds, Eurozone budget and a banking union, and by defending existing policies like the expansionary ECB policy. In contrast, members of the German parliament on average oppose all these measures except for the banking union. Regarding EMU reforms, France takes an intermediate position on most questions, often leaning toward the Italian side. Interestingly, however, for EU institutions a broad consensus emerges on some reforms. For instance, all three parliaments would agree in providing the EU parliament with the right of proposing new legislation, at the moment an exclusive competence of the EU Commission.

Moreover, in almost all areas, preferences among German parliamentarians are highly divided along political lines, including members of the parties which belong to the current governing ‘grand coalition’. While Social Democrats in Germany favour a number of policy and reform issues, which would make an agreement with Italian and French MPs conceivable, Christian Democrats are often quite opposed to most proposals. The completion of the banking union gathers the most support, as the opposition of German Christian Democrats is relatively mild.

A third insight comes from comparing the outcomes of our surveys in 2016 (Blesse et al. 2019) and 2018. Even though the comparison is limited because our first survey covered only France and Germany and had fewer questions, it nonetheless allows us to establish how stable these opinions are over time. In 2018, there was marginally more support for the expansionary policy of the ECB, but substantially lower support for a relaxation of the Stability and Growth Pact. By contrast, we find a stability in opinions on reform issues concerning a European Unemployment Insurance and Eurobonds.

Fourth, we analyse the views of ‘populist’ parties, which have risen to prominence in many European countries over the last few years. We follow the literature and define Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, and Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) and Lega in Italy1 as populist parties (Guriev and Papaioannou 2020). We find that populists’ views across Germany and Italy are not synchronized and do more generally not easily line up. Hence, among populist parties, a country-specific perspective dominates the political party attachment in the EU parliament.

Tackling EU taxation issues

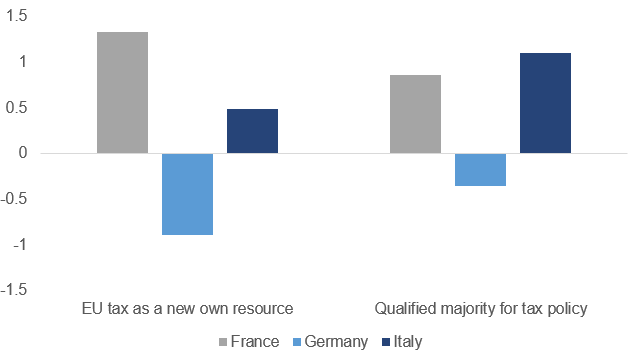

With NG-EU, Member States reached an important agreement, which is a first step in fighting the Covid-19 crisis (Beck 2020). However, the Council still has to find a consensus on the new own tax resources which would be used to finance the interests and the principal of the debt raised in the next budget cycle. Aside from the plastic levy that should start in 2021, additional resources could come from environmental (e.g. carbon tax) and digital taxation that should be in place no later than 2023. The introduction of these new taxes has to obtain the consensus of all Member States and needs to be ratified by national parliaments. Looking at the results of our survey, an agreement on these issues does not seem straightforward. While French MPs are the most supportive of an own EU tax as a form of autonomous funding for the EU budget, Italian parliamentarians are moderately supportive of it. German MPs are mostly opposed to it (Figure 1A).

Figure 1A Agreement on tax issues by Member States

Notes: Scores range from -4 ("Disagree") to +4 (Agree). Average opinions are weighted using the inverse response probability (see Blesse et al. 2020).

Source: Authors' calculations from 2018 survey.

A deal on tax policy could be easier to reach if the Council switched from unanimity to qualified majority voting on these issues. Interestingly, we find that there is no clear opposition to this institutional change in our three countries, since French and Italian MPs share a moderate support of majority voting at the EU level on taxes, while German MPs hold on average a mildly negative view.

At the party level, an own EU tax is welcome among National MPs associated with the group of Renew Europe and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D). By contrast, MPs associated with the European People’s Party (EPP) and M5S are opposed but close to indifferent. Identity and Democracy (ID) members stand in strong opposition to an own EU tax source. A somewhat similar picture arises for majority voting on taxes. While ID members are strongly opposed to this, majority voting finds varying degrees of support among other parties. The strongest support for a new voting mechanism is found among MPs associated with S&D. MPs associated with EPP are close to neutral regarding this proposal and Renew Europe MPs mildly support it (Figure 1.B).

Figure 1B Agreement on tax issues by party

Notes: Scores range from -4 ("Disagree") to +4 (Agree). Average opinions are weighted using the inverse response probability (see Blesse et al. 2020).

Source: Authors' calculations from 2018 survey.

We compare these results with the ones from the 2016 survey. The only question on institutional reforms in both surveys is the one on majority voting regarding tax policy. Interestingly, the proposal has gained stronger support among MPs associated with S&D, and milder support among Renew Europe ones.

Perspectives

The Covid-19 crisis has led to the introduction of new and important tools at the EU level to fight the common emergency and support the countries that are hit hardest by the crisis. However, these tools are only temporary and the mere size of the crisis played a role in overcoming the long-term diffidence in a number of countries to common instruments such as joint debt or EU unemployment benefits, certified by our 2016 and 2018 surveys. Moral hazard issues and national debt sustainability problems remain unaddressed. It is however telling and in line with the results of our 2018 survey that all three Parliaments, and particularly the German MPs, were on average less reluctant to support European-level fiscal institutions than risk-sharing mechanisms. This might explain why a solution to the Covid-19 crisis was sought through European institutions, such as the EU budget. This also suggests that the political support for deepening European integration in the long-term might be easier to build by creating truly European fiscal institutions. However, as the debate on the EU own tax shows, European countries are still very far from agreeing on this solution.

Authors' note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Confindustria.

References

Alesina, A, G Tabellini and F Trebbi (2017), “Is Europe an Optimal Political Area?”, Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 169-213.

Beck, T (2020), “A Hamiltonian glimpse in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 27 July.

Blesse, S, P C Boyer, F Heinemann, E Janeba and A Raj (2019), “European Monetary Union reform preferences of French and German parliamentarians”, European Union Politics 20(3): 406–424.

Blesse, S, M Bordignon, P C Boyer, P Carapella, F Heinemann, E Janeba and A Raj (2020), “The future of the European project: survey results from members of national parliaments in France, Italy and Germany”, CEPR Discussion Paper No 15021.

Bordignon, M and G Tabellini (2020), “The EU response to the coronavirus crisis: How to get more bang for the buck”, VoxEU.org, 13 May.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2020), “The euro area in the age of COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 22 May.

European Fiscal Board (2019), Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two pack legislation.

Guiso, L, H Herrera, M Morelli, T Sonno (2019), “Global crises and populism: the role of Eurozone institutions”, Economic Policy 34: 95–139.

Guriev, S and E Papaioannou (2020), “The political economy of populism”, CEPR Discussion Paper No 14433.

Spolaore, E (2016), “The Political Economy of European Integration”, In: Baldinger, H and V Nitsch (eds), The Handbook of the Economics of European Integration, Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 435–448.

Endnotes

1 To guarantee anonymity of respondents, we could not use the replies by members of the Rassemblement National party in the French Parliament.