Many online platforms have been providing digital goods and services to consumers at zero monetary cost. But consumers, in fact, exchange their personal data for 'free' digital goods and services, and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal demonstrates that there is no such thing as a free lunch in the digital economy.

Some economists have attempted to measure the welfare effects of 'free' digital goods and services (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2018). As large data holders, online platform firms can get significant economic benefits by monetising data. Therefore, it is a misnomer to call these goods and services 'free', and welfare analysis without considering the value of data can mislead policy analysis. The proliferation of 'free' digital goods and services challenges policymakers who rely on prices to indicate a good’s value, and also corporate managers and investors who need to know how to value data, which is a crucial input for the innovation and production of digital goods and services.

Data are hard to value in two ways:

- Conceptual difficulties. One needs to understand how online platforms create values from data and monetise data. But getting data and information from online platform firms is difficult (Demunter 2018).

- Empirical problems. Data are intangible capital that are generally hard to measure. There is no arms-length market for most intangibles, and most data are developed for a firm’s own use. And unlike R&D assets that may depreciate due to obsolescence, data can create new value through data fusion and innovations in data-driven business models – unique features that create unprecedented challenges in measurement.

The value of data and the data value chain

We have attempted to value data both conceptually and empirically (Li et al. 2019). We selected seven major types of online platforms that have different data-driven business models and conducted a case study of each using the available public data and information. Using the dimensions of data flows, value creation for consumers, value creation for third parties, and how an online platform firm monetises its data, we could examine their data-driven business models.

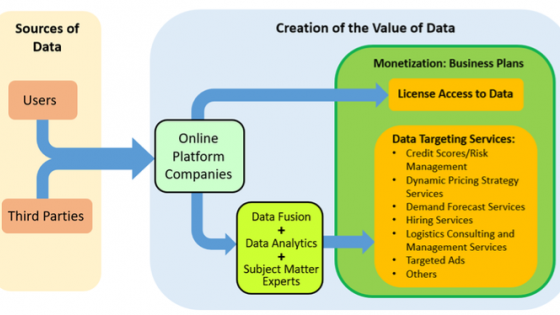

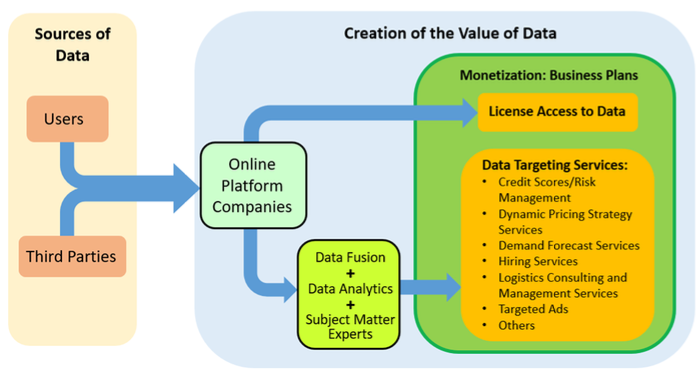

Figure 1 illustrates how the value of data is created by online platform firms, and how online platform firms monetise that data.

Figure 1 Creation of the value of data

Source: Li et al. (2019)

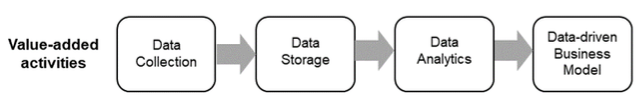

We then defined the data value chain (Figure 2), which indicates how online platform firms create value from data. Online platforms exemplify the concepts of the data value chain, and vertical integration within the chain. For platform firms, understanding the data value chain can help identify the right approach to value data.

Figure 2 Data value chain

Source: Li et al. (2019)

A new approach to valuing data

There are three conventional approaches to measure the value of economic goods: cost-based, market-based, and income-based. All have serious drawbacks and limitations when valuing the data owned by online platform firms. For example, a cost-based approach, such as using the salaries of data analysts and the costs of data centres, is likely to significantly underestimate the value of data; clearly so – many online platform firms outsource data centres to firms like Amazon and Microsoft to exploit the benefits of cheap and flexible cloud services.

We propose a new approach to valuing data. Our sources are the 10K reports of online platform firms, including Amazon, Booking Holdings, eBay, and Google, between 2000 and 2017. Most value in the chain in Figure 2 is generated when a firm has a data-driven business model. This relies on investments in that business model, which can be measured by investments in organisational capital.

Following earlier studies, we use selling, general, and administrative expenses as a proxy for a firm’s investment in organisational capital. Firms report this expense in their annual income statements. It includes most of the expenditures that generate organisational capital, such as employee training costs, brand enhancement costs, consulting fees, and supply chain management costs.

We also adopt the R&D depreciation model in Li and Hall (2018) to estimate the depreciation rates of the organisational capital for online platform firms that publish this data. This R&D depreciation model is a forward-looking profit model that uses firm-level data on sales and investments in intangible capital to identify the optimal solution of the firm-level depreciation rate of intangible capital.

Following Hall (1993), we construct stocks of organisational capital and calculate the associated growth rates for the four firms. The combination of these elements allows us to estimate the value of intangibles.

Our approach indicates that data can have enormous value (Table 1). For example, in 2017, the value of data derived from Amazon's business model can account for 16% of the firm's market valuation, and has an annual growth rate of 35%.

Table 1 Measurement of the value of data for selected firms

Source: Li et al. (2019)

The social value of data

Consumers barter their data for 'free' digital goods and services, and the barter transaction may hide a key source of the value of data – one consumer’s transaction record has zero or little value, but many, taken together, can reveal statistical regularities and potentially have non-negligible or substantial value.

In this sense, a consumer’s transaction record has a positive externality, because it can benefit other consumers by improving the predictive power of the platform’s matching algorithm. This reduces transaction costs for both consumers and third parties. In theory, summing the transaction costs needed to create the same matching outcome without online platforms can gauge the social value of data, and we have proposed a theoretical formulation to do this (Li et al. 2019). Online platforms may capture much of the social value of data by internalising this positive externality.

Conclusion

Online platforms have created tremendous value from data. We find that they vary in the degree of vertical integration in the data value chain, and that variation can determine how they monetise their data and how much of the economic benefit of data they can capture.

Online platforms with in-house data analytics capabilities and monetisation strategies can produce much greater values for data than those that outsource data analytics work, and more vertical integration means firms benefit more from data. Because the value of data is created on the firm side and because consumers lack the knowledge to value their own data, online platform firms also capture most of the value of these data. This may cover their investment costs in, for example, developing AI algorithms and can also be profitable.

Valuation of data is important at two levels:

- The firm level. As AI is becoming cheap, data decide the overall power and accuracy of an algorithm, and so are vital for firm competitiveness. Therefore an appropriate valuation of data determines business strategies on investment in data, competitive edge through data, and monetising data.

- The national level. National accounts should incorporate this new asset into the calculation of GDP and productivity growth. Given the existence of the virtuous cycle between AI and data, it is one of the key sources of firm competitiveness and therefore comparative advantage for a country in the global data economy.

The valuation of data therefore has important policy implications for innovation, investment, trade, and growth.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are solely those of the authors and should not be attributed to any organisation with which they are affiliated, including the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

References

Brynjolfsson, E, A Collis, W E Diewert, F Eggers, and K J Fox (2018), "The Digital Economy, GDP and Consumer Welfare: Theory and Evidence", Sixth IMF Statistical Forum proceeding papers.

Demunter, C (2018), "Towards a Taxonomy of Platforms in the Collaborative Economy: Outcomes of a Workshop on Measuring the Collaborative Economy", presented at the 2018 OECD Workshop on Online Platforms, Cloud Computing and Related Products, 6 September.

Hall, B H (1993), "The Stock Market’s Valuation of R&D Investment During the 1980s", American Economic Review 83(2): 259-264.

Li, W C Y and B H Hall (2018), "Depreciation of Business R&D Capital", Review of Income and Wealth.

Li, W C Y, M Nirei, and K Yamana (2019), "Value of Data: There’s No Such Thing as a Free Lunch in the Digital Economy", RIETI discussion paper 19-E-022.

OECD (2018), Online Platforms: A Practical Approach to Their Economic and Social Impacts, Paris.