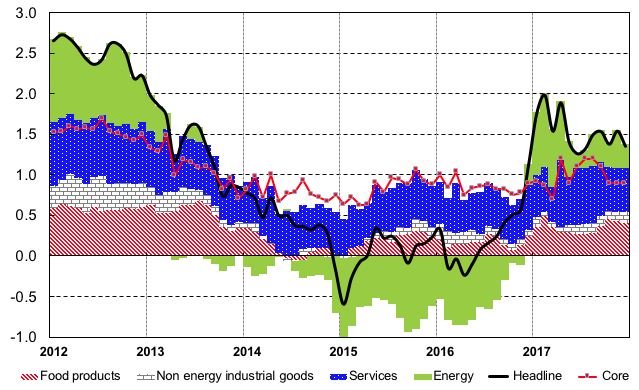

Between 2014 and 2016 falling oil prices dragged down headline inflation in the euro area. The HICP index remained below 1%, falling into negative territory at various times. Inflation picked up in early 2017, as the contribution of the energy components switched from negative to positive and economic recovery strengthened (Figure 1). More recently, as that contribution has receded, inflation has weakened again (to 1.2% in February 2018).

Figure 1 HICP inflation in the euro area and contribution of main components

Note: based on HICP data, contributions of different index components to headline inflation are expressed in percentage points.

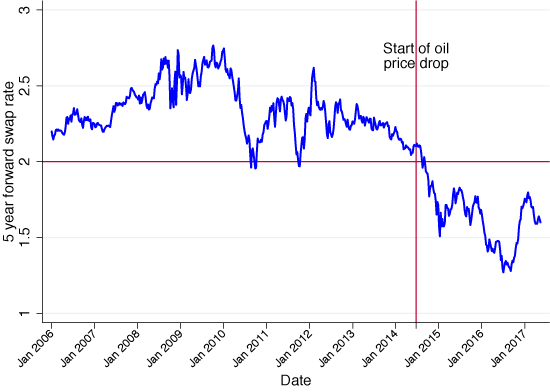

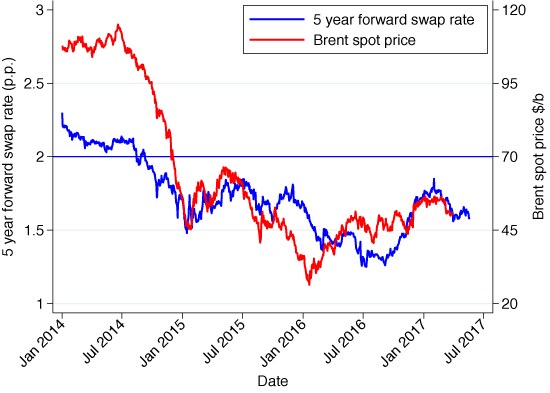

At the same time, different measures of inflation expectations – including long-term ones – drifted away from levels consistent with the monetary policy objective. Some researchers (Darvas and Hüttl 2016, Elliott et al. 2015) concluded that this may indicate the existence of a direct link between the persistent fall in oil prices and market-based long-term inflation expectations, as suggested by the close co-movements between the two phenomena over the last few years (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Market-based long-term inflation expectations in the euro area and oil prices

Similarly, a recent VoxEU column (Hasenzagl et al. 2018) looks at the determinants of inflation dynamics and states that the “oil cycle does not affect the output gap and is transmitted to prices as a purely expectational component”.

The claim that, in normal times, energy prices have a direct influence on long-term inflation expectations is puzzling, as it seems to imply that monetary policy is not able to offset price shocks even five or ten years down the road. If confirmed, it could have significant implications on how inflation dynamics are forecast. Hence, we believe that the claim warrants further scrutiny.

In a recent paper, using daily data from the euro area, we present estimates confirming that oil price changes have been positively and significantly correlated to market-based inflation expectations1 since the Global Crisis (Conflitti and Christadoro 2018). Even the five-year-ahead, five-year forward return on swaps (i.e. the difference between the ten-year and the five-year swaps), a key measure for monetary policy,2 shows a statistically significant correlation with oil prices.

However, this is only true in a simple regression that does not take into account other relevant variables. A more thorough analysis leads to different conclusions.

Falling oil prices, weak demand, and the disanchoring of inflation expectations

Since 2008, stock markets in advanced economies have moved in lockstep with oil prices. This is somewhat puzzling – historically the correlation has been either negative or absent, as oil prices are a drag on growth for oil-importing economies. The positive relationship likely arose as a softening of global aggregate demand and rising fears of weak global recovery affected both oil and stock prices (Bernanke 2016).

This suggests that, under certain conditions, the correlation between oil prices and long-term inflation expectations may be spurious. To ascertain whether this is the case, we estimate a model where we control for macroeconomic developments (like changes in stock prices and economic surprises). In this case, over the full sample (2006-2017) the relationship between oil prices and inflation expectations wanes. However, it remains significant for the 2014-16 period, when oil prices fell markedly, and the recovery looked weak and uncertain – especially in the euro area.

The 2014-16 period is also remarkable in that the correlation between short- and long-term inflation expectations rose from basically zero prior to the financial crisis to 0.4% in the period from June 2014 to January 2016, as oil prices fell from $110 per barrel to less than $30.3

A possible rationalisation of this increase is that the persistence of low inflation raised fears that the global economy (at least in advanced countries) was on the brink of a secular stagnation, and that monetary policy was unable or unwilling to restore price stability (Neri and Notarpietro 2015, Obstfeld et al. 2016).

In this situation, negative shocks to demand and prices are likely to affect expectations beyond the short term. Indeed, as pointed out in the literature, short- and long-term inflation expectations have become more synchronous, which is evidence of inflation expectations disanchoring, as argued by (among others) Natoli and Sigalotti (2016). The rise in the correlation between long-term inflation expectations and oil price changes is therefore an indirect effect of inflation expectations disanchoring.

Again, to find out whether this mechanism was indeed at work in 2014-16, we estimate a model that controls for the impact of variations in short-term inflation expectations on expectations further away in time. The effect of oil price changes on long-term inflation expectations vanishes completely once we control for short-term inflation expectations. This finding confirms that oil price changes seem to affect longer-term inflation expectations only because, and to the extent that, their impact transits through short-term ones.

Including monetary policy surprises in the model, the effect of oil prices on long-term inflation expectations is further reduced over the 2014-16 period, thanks to their mitigating effect on the correlation between short- and long-term expectations. This also suggests that factors other than oil prices influenced the transmission of oil shocks to inflation expectations.

Hence, the claim that oil prices directly affect inflation expectations at horizons relevant for monetary policy credibility is much weakened by our results.

What can we expect with higher oil prices?

For quite some time, inflation has been very low in advanced economies. Since 2014, falling oil prices have contributed to this trend. However, the strong relationship between oil prices and long-term inflation expectations observed over the last few years is spurious. Our results show that the impact of oil prices on long-term inflation expectations is much weakened, once the economic cycle (proxied by stock market and confidence indicators) is taken into account. Furthermore, the direct effect of oil prices on long-term inflation expectations is never significant once we control for their impact on short-term ones.

Going forward, the doubling of oil prices from the lows reached in 2016 has helped inflation recover somewhat in the euro area, but will not per se result in a sustained adjustment in price dynamics, nor will it lift long-term inflation expectations. Our results suggest that, in order to achieve a sustained adjustment of both actual and expected inflation, a firming of the recovery is needed. In turn, this arguably requires that monetary policy be perceived as strongly and credibly committed to this aim.

References

Conflitti, C, and R Cristadoro (2018), “Oil prices and inflation expectations”, Banca d’Italia, Occasional Papers no. 423.

Darvas, Z, and P Hüttl (2016), “Oil prices and inflation expectations”, Bruegel, 21 January.

Draghi, M (2014), “Unemployment in the euro area”, Annual Central Bank Symposium, Jackson Hole, 22 August.

Elliott, D, C Jackson, M Raczko, and M Roberts-Sklar (2015), “Does oil drive financial market measures of inflation expectations”, Bank of England, 20 October.

Hasenzagl T, F Pellegrino, L Reichlin, and G Ricco (2018), “Low inflation for longer”, VoxEU.org, 15 January.

Natoli, F, and L Sigalotti (2017), “An indicator of inflation expectations anchoring”, Banca d’Italia, Working Papers, no. 1103.

Neri, S, and A Notarpietro (2015), “The macroeconomic effects of low and falling inflation at the zero lower bound”, Banca d’Italia, Working Papers, no. 1040.

Obstfeld M, G M Milesi-Ferretti, and R Arezki (2016), “Oil Prices and the Global Economy: It’s Complicated”, IMF Blog, 24 March.

Sussman N, and O Zohar (2015), “Oil prices, inflation expectations, and monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

Endnotes

[1] We use simple differences in inflation swaps’ returns, often called ‘inflation compensations’, to underscore how factors other than inflation expectations, like varying risk and liquidity premia, can affect their behaviour. We checked for differentiated impacts of oil prices on the risk and pure inflation component of inflation compensations, albeit only at a monthly frequency, and find no evidence of any.

[2] This difference is largely determined by beliefs about inflation over a 5-year horizon that starts five years from now, therefore it should not reflect current shocks that monetary policy can offset, nor should it be related to changes in inflation expectation at a short-term horizon. This is the metric usually used for defining long-term inflation (Draghi 2014).

[3] This is referred to as the correlation between 1-year ahead inflation swap rates and the 5-year, 5-year forward rates.