When pressed by a Parliamentary Committee in 1930 to explain the Bank of England’s actions, Montagu Norman replied: “Reasons, Mr Chairman? I don’t have reasons, I have instincts”.

Elvis Presley was in line with the Montagu Norman view when he sang “a little less conversation, a little more action”. Today, instincts are not sufficient. There is a need for reasons and justifications. Andy Haldane argues for “a little more conversation, a little less action” (Haldane (2017). Paul Romer, when he was chief economist at the World Bank, emphasised the need for clear language.

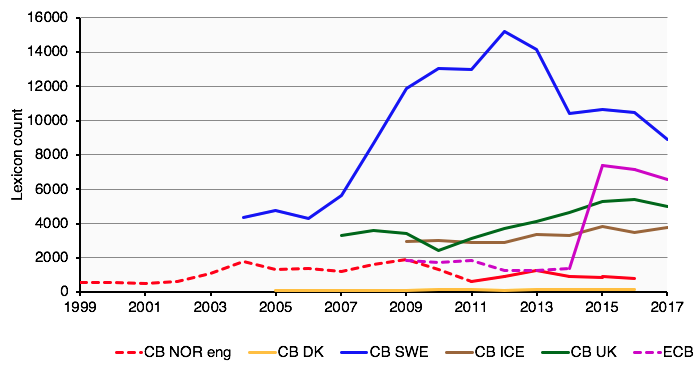

If we look at a sample of central banks and how they justify their decisions in their minutes, we observe that these texts vary considerably in length (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Number of words in central bank minutes

Among central banks, the Swedish central bank writes the longest text and the Icelandic central bank one of the shortest. The length of the ECB ‘minutes’ increased from fewer than 2,000 words to around 7,000 when they switched from the “Introduction to the press conference” to the “Account of the monetary policy meeting”.

The central bank is not the only important public institution that exercises power in society. A supreme court also does so. The number of words supreme courts use to justify their decisions varies even more (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Number of words in supreme court judgements

The European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber (ECHR) is in a league of its own, with more than 30,000 words on average in 2017. The Supreme Court of the UK (SC UK) is a good number two. Judgements in the Scandinavian countries average between 2,000 and 4,000 words.

Optimal minutes?

Is there a norm for what is a ‘good’ length for the minutes, and how should they be written? Andy Haldane does not go into what the criteria for ‘good’ justifications should be, nor does Paul Romer. We address this issue in a recent study (Qvigstad and Schei 2018).

We propose criteria not only for central banks, but also for supreme courts. In a liberal democracy, it goes without saying that this exercise of power must be accounted for. Institutions also prepare minutes as a record of why they reached a decision, as similar cases may arise in the future. For the supreme court, key factors here include the normative effect of its judgements and the fundamental principle of equality under the law. For the central bank, they include consistency in economic thinking and economic decisions. Decisions influence expectations. A case will often only be heard by the supreme court if it concerns a matter of principle.

Perhaps the central banks and supreme courts can learn from each other in writing justifications for their decisions?

Four criteria for ‘good’ justifications

Based on our combined experience of more than 30 years in central banking and the supreme court, including six years as vice chairman of the board, and 14 years as chief justice, we propose the following four criteria for ‘good’ justifications:

Criterion 1: The justifications should be technically sound

When a decision is made, it is reasonable to require information to be provided on who made it, on what legal basis they made it, and whether all procedures have been correctly followed.

Criterion 2: The justifications should be functional

The decision must be explained logically, setting out the premises, analyses, assessments and conclusion. The justifications must be written in clear language so that it can be understood by and tailored to those affected by the decision. The justifications must be written efficiently, concentrating on the key points.

Criterion 3: The justifications should be open and complete

The justifications should also shed light on the path leading to the decision.Which points proved particularly hard? Which considerations led to the decision turning out the way it did, but presented difficulties?

Criterion 4: The justifications should be formulated with the future in mind

A supreme court judgement impacts directly on the parties to the case but also has a more general normative effect. Central bank decisions will affect expectations about the bank’s future behaviour. The justifications need to be written with the decision’s normative effects and impact on expectations in mind.

Do central banks and supreme courts live up the criteria?

We assess a selection of supreme court judgements and monetary policy decisions in various countries qualitatively against our criteria, and find that practice largely conforms to the criteria. Criterion 1 is generally being met. Criterion 2 is being met, although the institutions do so in different ways. The institutions are good at providing logical justifications for their decisions.

Those with an interest in language as such will probably take pleasure in reading the judgements of the UK Supreme Court but be less keen on the minutes of the ECJ. Not all justifications are written as efficiently as some. There has been a clear change at the UK Supreme Court. Previously, it was normal practice for each justice to write his or her own complete opinion, even if there was a consensus on the conclusion. This could make it difficult to determine exactly what the legal precedent was. There has been a conscious transition to producing collective justifications.

Many of the factors in favour of collective writing of supreme court judgements also apply to the writing of the minutes of monetary policy meetings. The same trend of collective writing has been evident among some central banks. The Swedish central bank, however, does not follow this trend. Each member of the Executive Board explains his or her own particular vote. This results in a series of monologues rather than a collective explanation. Alan Blinder believes that a central bank that speaks with a cacophony of voices has no voice at all. Otmar Issing believes that there is also a danger that individual minutes provide an incentive for individual members to put themselves ahead of the institution.

Criterion 3 is the one we consider the most challenging. We would like the justifications to reflect the actual decision-making process to a greater extent. There have, however, been moves in the right direction over time. There is a clear tendency for supreme court justices to spend more time clarifying the premises for their exercise of discretion. Criterion 4 is being fully met in our opinion. Considerable effort is put into clarifying the precedential effect – the application of the law that is to be normative.

Clear language?

One element of our second criterion is that the justifications should be written in clear language. We look at more than 6,000 monetary policy decisions and supreme court judgements to assess whether they meet this requirement. It will be no surprise that not all of them do so.

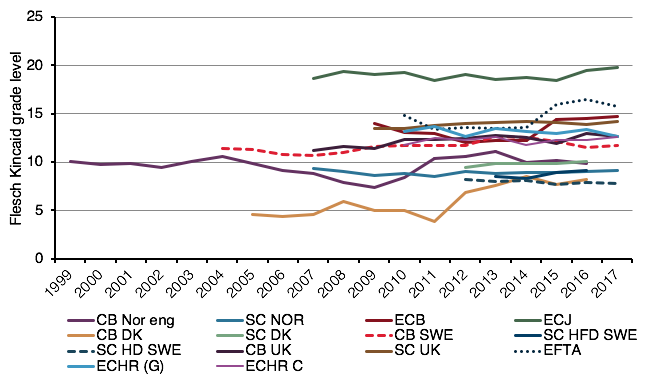

Many readability tests are calibrated to show how many years of education are required to understand the text. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test is for example calibrated in this way.1 We have calculated the readability of the justifications given by a selection of central banks and supreme courts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level for central bank minutes and supreme court judgements in selected countries

Since the ECB began to publish formal minutes, the complexity of its language has increased. More than 14 years’ education is now required to understand them. The Swedish central bank and the Bank of England also use relatively complex language. Around 12 years’ education is needed to understand the justifications.

The ECJ’s judgements present a very high level of complexity for readers, requiring almost 20 years’ education to be understood. The Scandinavian supreme courts come out between eight and ten years. Fourteen years’ education is required to digest UK court decisions.

Better than the World Bank?

An analysis of the language of World Bank documents in the period 1946-2012 shows that the frequency of the word “and” increased from 2.6% on average to almost 7% at the end of the period (Moretti and Pestre 2015). Paul Romer issued a directive saying that this conjunction should not account for more than 2.6% of the words in any report. The directive led to considerable consternation at the World Bank. We perform the same tests on central banks and supreme courts and find that these institutions’ language has not moved in the same negative direction as the World Bank.

Conclusion

Former Bank of England governor Mervyn King argued that the design of an institution “must reflect history and experience”. This is what economists refer to as ‘path dependence’. We wonder, however, whether there is rather too much path dependence in many cases, and whether the institutions in question might benefit from looking at trends and learning from other institutions both at home and abroad. We think that the Swedish Riksbank could look at the way the UK Supreme Court’s justifications have developed, the European Court of Justice could learn something from Paul Romer’s insistence on clear language, and the European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber should go on a study tour to Reykjavik and be inspired by the length and clarity of the Central Bank of Iceland’s minutes.

References

Haldane, A G (2017), “A Little More Conversation A Little Less Action”, Speech, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy Conference, 31 March 2017, Bank of England

Moretti, F and D Pestre (2015), “Bankspeak, The Language of World Bank Reports 1946-2012”, Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab,

Qvigstad, J F and T Schei (2018), "Criteria for “good” justifications", Norges Bank Working Paper 6.

Endnotes

[1 ]Donald Trump’s speeches during his presidential campaign required just four years at school to understand. Elvis’s lyrics require six years. Pennsylvania was the first US state to require car insurance documents to be written simply enough that they can be understood by those with nine years’ education.