Breastfeeding has long been considered the most beneficial source of nutrition for infants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). It has been linked to strengthened immunity, reduced likelihood of post-neonatal and SIDS mortality, and decreases in hospitalisations and deaths from infectious diseases, diarrhoea, and respiratory infections (Chen and Rogan 2004, American Academy of Pediatrics 2005, Grummer-Strawn and Rollins 2015, Victora et al. 2016). Breastfed children face lower risks of adverse, long-term health outcomes as well, including obesity, type II diabetes, and asthma (Victora et al. 2016).1

In 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Services put forth Healthy People 2020 targets to increase the prevalence and duration of breastfeeding among US mothers. These efforts have achieved uneven success. Overall, US mothers breastfeed their infants at higher rates today than at any point in documented history, but low-income mothers, who were more likely to initiate breastfeeding through the 1960s, have become less likely to do so, while the reverse is true for middle- and high-income women (Dennis 2002, Dubois and Girard 2003, Callen and Pinelli 2004, Victora et al. 2016).

Our study

A leading reason for mothers to stop breastfeeding is the need to return to work (Thulier and Mercer 2009). The availability of paid family leave following the birth of a child may increase a mother’s time at home and the incidence or duration of breastfeeding.

In recent work (Pac et al. 2019), we provide what is to our knowledge the first US evidence on the relationship between paid family leave and breastfeeding using a large, representative sample combined with appropriate econometric techniques. To do so, we exploit the temporal and geographic variation in access to leave related to California’s 2004 implementation of paid family leave.

California is the most useful state for examining the effects of paid parental leave because the other existing state programmes are either too recent to have sufficient post-programme data (Rhode Island, New York) or too small to have sufficient sample size to study disparities in outcomes across population subgroups (New Jersey).

Our sample contains over 270,000 mother-child pairs representing births between 2000 and 2012 and is drawn from the restricted-use 2003–2014 National Immunization Survey. We employ difference-in-difference models using synthetic control methods to compare the pre- versus post-law differences in outcomes of mother-child pairs in California to those outside the state. The synthetic control method is important because the parallel trends assumption is violated when employing a standard difference-in-difference methodology with all mothers from outside California as the control group.

Results

Our results suggest that paid family leave significantly increases overall breastfeeding duration by nearly 18 days (from a base of 221 days) and breastfeeding for at least six months by 4.9 percentage points (from an average of 53% before implementation of the paid family leave law) while having little effect on the probability of initiating breastfeeding.2

Since disadvantaged mothers may be more responsive to paid family leave than their advantaged peers, we also examine whether paid family leave has heterogeneous treatment effects by estimating models stratified by several markers of disadvantage, including maternal age and education, poverty status, whether the family receives Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or has experienced a disruption in phone service.

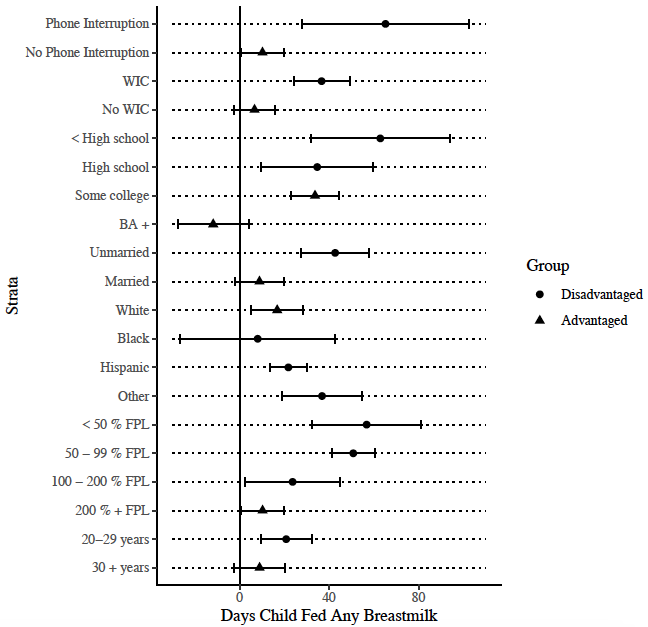

Figure 1 shows that paid family leave has consistent positive effects on breastfeeding duration, with greater gains for some disadvantaged groups. For instance, respondents who experienced a phone interruption were estimated to increase the duration of breastfeeding by 65 days, with a corresponding 37-day increase for WIC recipients during the prior year, compared to little or no effect for their counterparts. Mothers with less than a high school education were predicted to breastfeed 63 additional days as the result of paid family leave, compared to around 35 days for high school graduates or those with some college, and to no change for college graduates. The estimates are also much larger for mothers at <50% or 50%-99% of the federal poverty line, compared to those with more financial resources, and for single versus married mothers.

Figure 1 Breastfeeding duration: Stratified models

Notes: Figure shows estimated effect of California’s paid family leave programme on the duration of breastfeeding (conditional on any breastfeeding). Estimates are represented by points with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals.

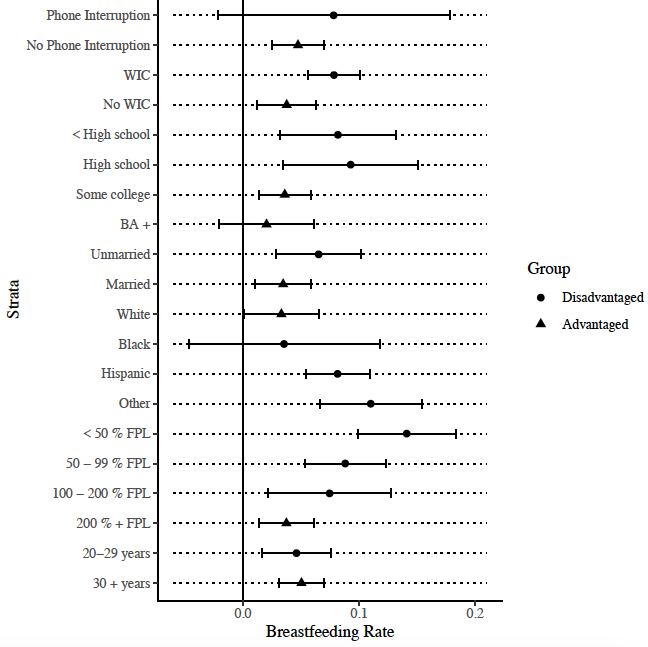

However, there are no clear racial differences. Figure 2 shows the same general pattern for breastfeeding at least six months, although the between-group differences are rarely statistically significant. For instance, paid family leave is associated with a 14 percentage point increase in the likelihood that respondents below 50% of the federal poverty line breastfeed at least six months and with corresponding 8 percentage point increases for WIC recipients and the non-college-educated. Similar results were obtained using a variety of robustness and sensitivity checks.

Figure 2 Breastfeeding for at least six months: Stratified models

Notes: Figure shows estimated effect of California’s paid family leave programme on the probability of breastfeeding for at least six months. Estimates are represented by points with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals.

Since the National Immunization Survey lacks information on maternal employment, we were not able to directly test whether the extensions in breastfeeding were concentrated among employed women, who would be directly affected by paid family leave.

We implemented two secondary analyses to partially overcome this limitation. First, we compared mothers residing in counties with high versus low rates of maternal labour force participation and employment. Consistent with there being a causal effect of paid family leave, the estimated impact of paid family leave on breastfeeding duration was stronger in the counties with higher labour force participation and employment rates, although the results for breastfeeding at least three or six months were somewhat mixed. Second, we examined and found evidence that women with the highest propensity to breastfeed, based upon their individual characteristics, experienced the greatest increases in breastfeeding duration as a result of California’s paid family leave programme.

Conclusions

Overall, we provide evidence that extending paid family leave to families in states without current mandates may increase breastfeeding durations, possibly leading to longer-term health improvements for children and mothers. Given that our positive findings are often concentrated among disadvantaged mothers, extensions of paid family leave may also reduce disparities in breastfeeding and associated outcomes. These distributional effects should be included in national benefit-cost calculations, along with the average effects of the law, such that improvements in breastfeeding duration are counted among the growing list of benefits of paid family leave. As breastfeeding has been found to affect long-term child and maternal health, any future efforts to evaluate the associated benefits of paid family leave should consider breastfeeding as a predominant mechanism.

The results of our research are especially timely given the current policy context in the US, where seven states and the District of Columbia have now enacted paid family leave legislation, and where discussions in Congress are picking up speed.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (2005), “AAP policy statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk”, Pediatrics.

Callen, J, and J Pinelli (2004), “Incidence and duration of breastfeeding for term infants in Canada, United States, Europe, and Australia: A literature review”, Birth 31(4): 285–92.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016), “Breastfeeding report card 2016”, 1–8.

Chen, A, and W J Rogan (2004), “Breastfeeding and the risk of postneonatal death in the United States”, Pediatrics 113(5): e435–39.

Dennis, C-L (2002), “Breastfeeding initiation and duration: A 1990-2000 literature review”, Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 31(1): 12–32.

Dubois, L, and M Girard (2003), “Social Determinants of initiation, duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding at the population level”, Canadian Journal of Public Health 94: 300–305.

Grummer-Strawn, L M, and N Rollins (2015), “Summarising the health effects of breastfeeding”, Acta Paediatrica 104(467): 1–2.

Pac, J E, A P Bartel, C J Ruhm and J Waldfogel (2019), “Paid family leave and breastfeeding: Evidence from California”, NBER Working Paper 25784.

Thulier, D, and J Mercer (2009), “Variables associated with breastfeeding duration”, Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 38(3): 259–68.

Victora, C G, R Bahl, A J D Barros, G V A França, S Horton, J Krasevec, S Murch, et al. (2016), “Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect”, The Lancet 387(10017): 475–90.

Endnotes

[1] These associations may not always indicate causal relationships since there is non-random selection into breastfeeding.

[2] These results are from models that also include controls for maternal age, education, poverty level, race/ethnicity, and marital status as well as child parity and gender. Synthetic control methods are used to determine the weighted set of control states.