Ever since we have been able to measure it, there has been a large gap in mortality between black and white Americans. Even in the years before the first set of reliable black mortality estimates, evidence was mounting that enslaved blacks were significantly shorter than whites in antebellum America (Margo and Steckel 1982).

Part of the racial health gap was due to the inadequate diet of blacks during slavery, and another was due to slavery itself. For instance, enslaved black women were forced to work up to within a week of giving birth and were then placed back in the fields only a few weeks after (Fogel and Engerman 1977). As a result, enslaved black women gave birth to some of the smallest babies ever observed (Steckel 1986). Thus, it is likely that the scars of slavery still appear in the intergenerational transmission of health for African Americans.

Since the end of chattel slavery, there has been marked improvement in the racial mortality gap. In 1900, black men could expect to live to age 42, nearly a decade less than white men. By 2010, the gap shrunk to five years, which does represent gains to black health. However, these gains were not so large when the recent increase in white mortality, popularly known as ‘deaths of despair’, is also brought into account (Case and Deaton 2017).

In the last century, many public health interventions undoubtedly played a role in closing the black-white mortality gap. These interventions – including public sanitation, medical care, the decline of infectious disease mortality, and improved living standards – increased longevity for blacks and whites, even if some of the benefits to blacks were unintended (Troesken 2004).

However, the gaps remain and likely explanations include income and wealth differences between the races, insurance coverage, health behaviours, environmental factors, and differential access to healthcare. Since we know that blacks are less likely to visit medical professionals, increasing access – via insurance and other public health services such as community health centres – has been seen as one route for improving black health outcomes (Bailey and Goodman-Bacon 2015). But will access to care close the mortality gap?

It depends on the care blacks get when they access the medical system. Recent evidence shows that blacks are prescribed fewer pain medications than whites and offered fewer treatments, both surgical and otherwise, relative to their white counterparts (Goyal et al. 2015). Physicians also exhibit significant bias in assessing the pain and treatment of their black patients (Hoffman et al. 2016). Physicians at times simply do not believe what their black patients tell them. They assign different treatments to blacks and whites as a result (Van Ryn and Burke 2000) and black health suffers the consequences. This includes blacks receiving poorer service from health professionals, and also blacks being more likely to avoid seeking medical care due to perceptions about racial bias in the medical profession.

Our study

The implications of physician racial bias are wide ranging. In our recent study (Eli et al. 2019), we investigate the effect of income on the black-white mortality gap in late 19th- and early 20th-century US and find that physician racial bias plays a large role. What is most remarkable is that physician bias plays a large role in the black–white mortality gap at a time in which medical care itself was not particularly beneficial to health.

Estimating the causal effect of income on health in the context of veterans’ pensions is not straightforward. Because veterans have to show proof of disability to qualify for a pension, sicker veterans receive high pension, which would make it seem as though higher pensions contribute to ill health.

Thus, to determine the effect of pension income on health, we leverage the fact that Union Army veterans of the American Civil War were randomly assigned to boards of examining physicians that evaluated the severity of illnesses and disabilities on which subsequent pension payments were based. We construct linkages of Union Army veterans to their physicians by digitising the entire history of physician turnover at the US Pension Bureau. We then observe the difference in physician ratings in cases in which a black and white veteran faced the same illness.

In our analysis, we use the average pension payment made to all other veterans evaluated by the physician of a particular veteran to measure physician bias. In other words, we determine how generous a physician has been to previous patients and use that estimate to predict how generous he will be to his current patient, while holding the type of illness constant. Since veterans cannot choose their physician, this measure of predicted income is exogenous and allows us to estimate the effect of an additional dollar of pension income on mortality and on the black–white mortality gap.

We find that an additional dollar in monthly pension income (equivalent to a 10% increase relative to the mean) led to an additional 0.3 years of life for all veterans. The disparity in pension income that resulted from doctor bias appears to explain nearly all of the gap in health outcomes between the races. Once we control for physician bias there is no residual racial disparity in mortality.

Furthermore, we show that evidence of bias is larger for black applicants who applied for a pension for the first time as they faced greater prejudice from physicians. We also find that physician bias was more pronounced for conditions that were difficult to diagnose and thus more subject to physician judgment. Indeed, when restricting the sample to those veterans who faced digestive illnesses, which were difficult to diagnose with the medical tools available to them, black veterans receive a much lower pension relative to whites. For illnesses which could be objectively diagnosed at the time, such as cardiovascular conditions, we do not find evidence of physician bias.

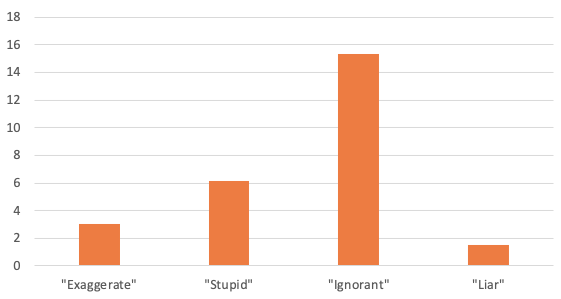

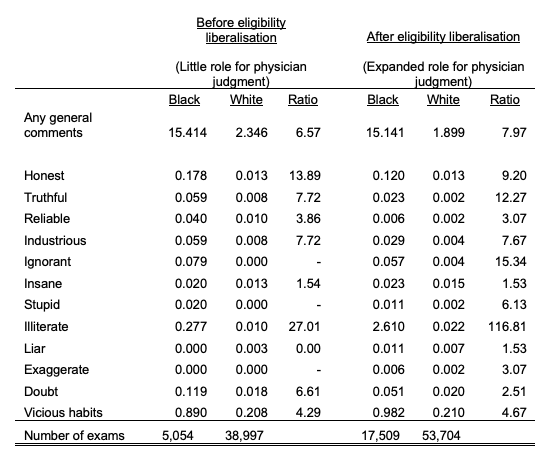

Textual analysis of both veteran and physician comments (Figure 1 and Table 1) reveal that despite the fact that black veterans were no more likely than white veterans to report pain, black veterans were more than twice as likely to be doubted by their physicians and more than three times as likely to be accused of ‘exaggerating’ their illness. Physicians were also six times as likely to describe black patients as ‘stupid’ and 15 times more likely to describe blacks as ‘ignorant’. These differences become even more stark when compared to those from before our sample period – a time in which eligibility requirements were stricter with little role for physician judgement.

While the pension laws were innovatively race-neutral with no eligibility differences for black and white veterans, we find numerous mentions of race in the physician comments. These comments were not medically relevant or important to the determination of eligibility and therefore offer further evidence of physician bias.

Figure 1 Black-to-white ratio of receiving negative comments from assessing physicians

Table 1 Physician comments before and after pension eligibility changes

What we highlight as a historical phenomenon continues to inform health policy today. For instance, one of the leading causes of disability in the general population is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and non-reversible asthma. The machine used to assess breathlessness caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – the spirometer – requires physicians to ‘eye-ball’ the race of the patient, since lung capacity is still assumed to be different across races as was first described in an 1869 study (Braun 2014). To be clear, the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease today is based on racial assumptions from 1869, where blacks were assumed to have lower lung capacity than whites. Because the spirometer calibrates a lower lung capacity for blacks as opposed to whites, blacks today are rated as less disabled than whites when applying for disability, even though they have the same diagnostic scores as whites.

Determining methods to reduce physician bias is essential to the closure of the racial mortality gap. Recent research shows that black doctors improve the health outcomes of their patients (Alsan et al. 2019), by making patients more likely to partake in preventative health services and additional procedures. This is nothing new in American medicine and solving the problems of health inequities has been part of the civil rights agenda for a long time (Nelson 2013). Part of the solution begins with recognising how systematic and structural these problems truly are.

References

Alsan, M, O Garrick and G C Graziani (2019), “Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland”, NBER Working Paper 24787.

Bailey, M J, and A Goodman-Bacon (2015), “The War on Poverty’s experiment in public medicine: Community health centers and the mortality of older Americans”, American Economic Review 105(3): 1067–1104.

Braun, L (2014), Breathing race into the machine: The surprising career of the spirometer from plantation to genetics, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Case, A, and A Deaton (2017), “Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017: 397-476.

Eli, S, T D Logan and B Miloucheva (2019), “Physician bias and racial disparities in health: Evidence from veterans’ pensions”, NBER Working Paper 25846.

Fogel, R W, and S L Engerman (1977), “Explaining the relative efficiency of slave agriculture in the antebellum South”, The American Economic Review 67(3): 275–296.

Goyal, M K, N Kuppermann, S D Cleary, S J Teach and J M Chamberlain (2015), “Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments”, JAMA Pediatrics 169(11): 996–1002.

Hoffman, K M, S Trawalter, J R Axt and M N Oliver (2016), “Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(16): 4296–4301.

Margo, R A, and R H Steckel (1982), “The heights of American slaves: New evidence on slave nutrition and health”, Social Science History 6(4): 516–538.

Nelson, A (2013). Body and soul: The Black Panther Party and the fight against medical discrimination. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Steckel, R H (1986), “A peculiar population: The nutrition, health, and mortality of American slaves from childhood to maturity”, The Journal of Economic History 46(3): 721–741.

Troesken, W (2004). Water, race, and disease, Cambridge, US: MIT Press.

Van Ryn, M, and J Burke (2000), “The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients”, Social Science and Medicine 50(6): 813–828.