An increasing number of cities worldwide are relying on surveillance cameras as a tool for preventing crimes and supporting investigations and prosecutions. However, not enough is known about the effect of surveillance cameras on crime, and in particular, little is known about whether cameras reduce crime or simply relocate criminal activity to other areas.

The effect of surveillance cameras on crime is ambiguous in the literature.1 Welsh and Farrington (2009) present a review of the empirical literature, which is mainly concentrated on small-scale experiences and focuses on partial equilibrium effects.2 In addition, only a few papers address the causality problem between the installation of cameras and crime. Exceptions include King et al. (2008), Hayes and Downs (2011), La Vigne at al. (2011), Priks (2014), Priks (2015), van Ours and Vollaard (2016), and Gomez-Cardona et al. (2017).

The impact of police-monitored cameras in Montevideo

In a forthcoming paper (Munyo and Rossi 2019) we study the impact of a large-scale introduction of police-monitored cameras in Montevideo (the capital city of Uruguay, with 1.5 million inhabitants). In 2013 the Ministry of the Interior of Uruguay started to install surveillance cameras in some areas of the city. These cameras are continuously watched by police officers located in a monitoring centre that combines video surveillance technology with the action of police patrol response.3

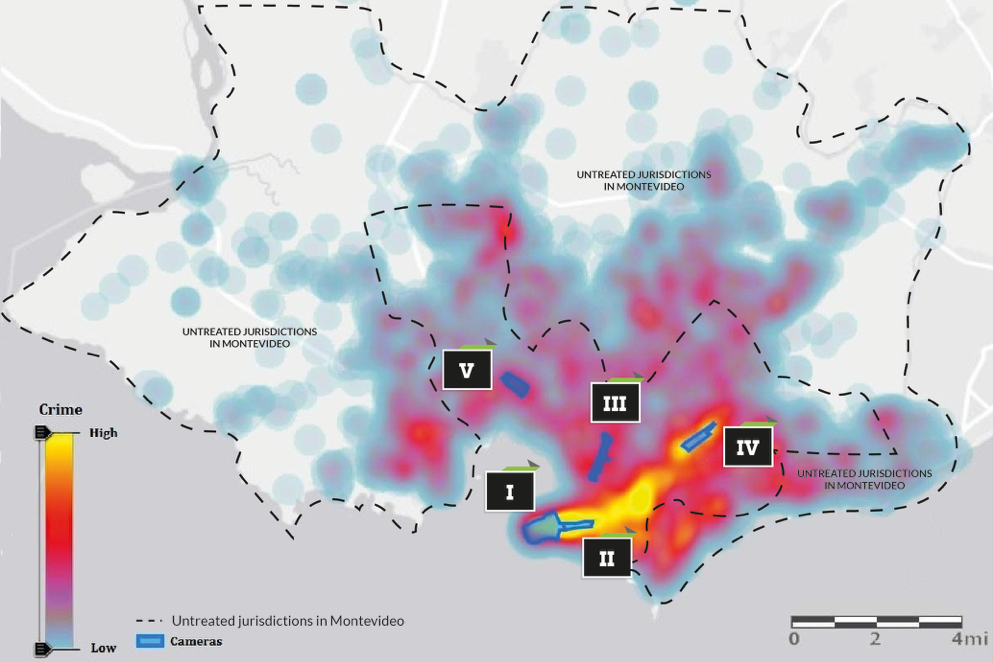

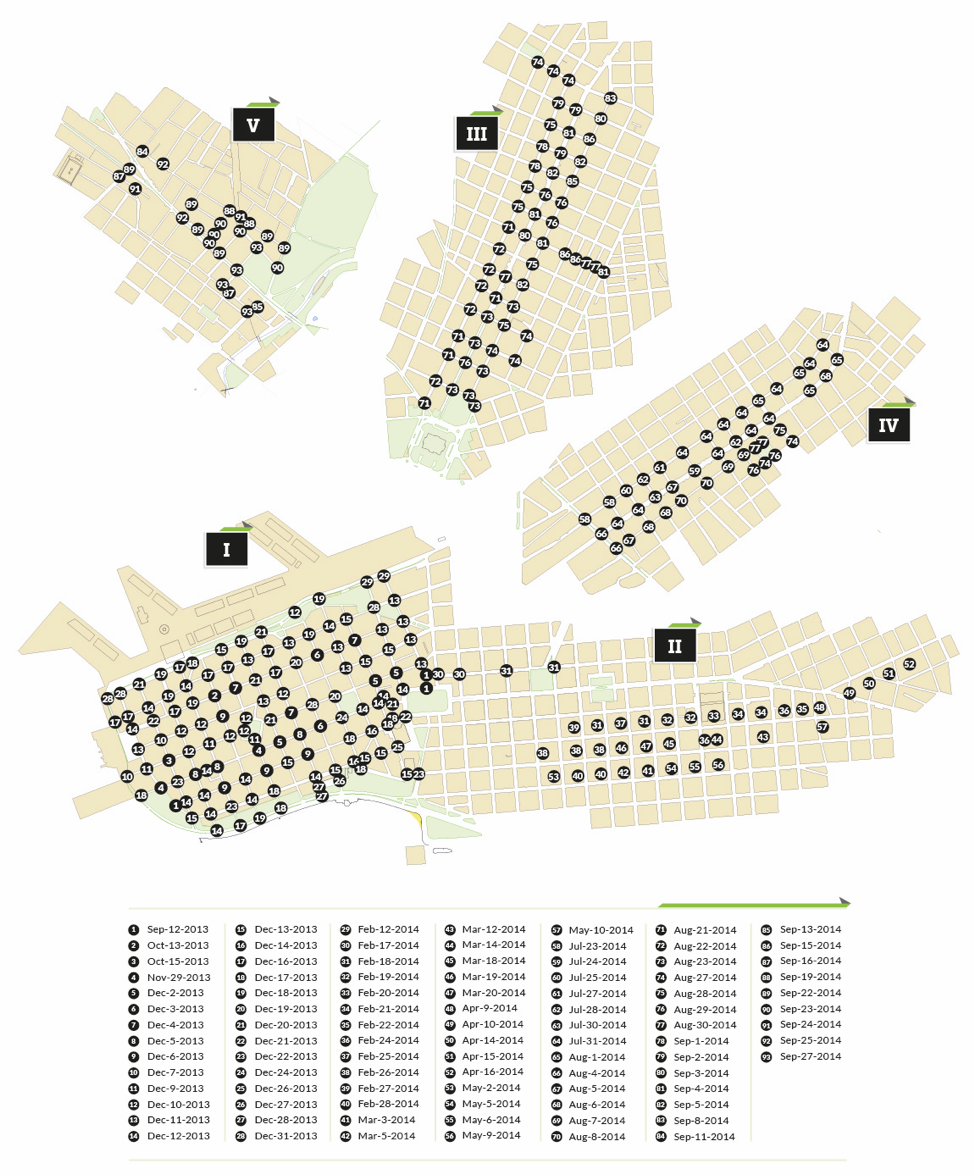

Figures 1 and 2 summarise the geographical distribution of the areas monitored by surveillance cameras, the variability in the installation dates across different street segments, and crime incidence in Montevideo in October 2012 (before the beginning of the programme). As usual, crime is clustered in small areas that include not only the street segments covered by police-monitored cameras, but also other areas all around the city.

Figure 1 Police-monitored areas and previous crime

Figure 2 Date and place of installation of the cameras

Areas where cameras are installed see a significant reduction in crime

In order to study the impact of this policy on crime, we take advantage of a unique database that includes the universe of reported crime in the entire city of Montevideo, by street segment, and the location and the time of the installation of all police monitoring cameras in the city. To identify the effect of police-monitored cameras on crime, we use a difference-in-differences approach that exploits the variability over time and space in the introduction of the cameras. Our estimates indicate that the presence of police-monitored cameras is associated with a reduction in crime of about 20% in treated areas of the city.

What is the rationale behind these results? In principle, the effect of police monitoring on crime could potentially work through deterrence (a police presence makes criminal activity less attractive) and incapacitation (police officers apprehend criminals, leaving fewer of them around to commit future crimes). Despite anecdotal evidence of arrests made by police patrols alerted by officers in the monitoring centre, our results are unlikely to reflect changes in the numbers of incarcerated criminals. Thus, we believe that our estimates should be interpreted as a deterrent effect of police monitoring on crime.4

Is there a displacement effect?

The reduction in crime in areas with police monitoring may be compensated by a ‘displacement effect’ – an increase in crime somewhere else. When we explore potential displacement effects, however, we do not find significant evidence.

Evidence on general equilibrium effects from anti-crime policies is scarce. Pricks (2015) analysed the effects of surveillance cameras on crime in the Stockholm subway system. He presents evidence that the introduction of the cameras reduced crime by approximately 25% and reports some evidence of local displacement. In a recent contribution, van Ours and Vollaard (2016) study the impact of the introduction of an electronic engine immobiliser in the EU. This anti-theft device reduced thefts of new (protected) cars. They also report some displacement to older (unprotected) cars. Our results suggest that crime displacement may depend on the particular setting of the policy implemented.

Additional findings

Our paper includes additional results. According to police authorities, theft and robbery are more likely to occur outdoors, and therefore are more likely to be prevented by means of surveillance cameras. Assault and domestic violence, on the other hand, are more likely to occur indoors and therefore less likely to be prevented by surveillance cameras. We follow the authorities’ classification and construct two variables: outdoor crime (thefts and robberies) and indoor crime (assaults and domestic violence). We find no impact of surveillance cameras on ‘indoor’ crime. In addition, when we use ‘outdoor’ crime as the dependent variable, the estimated coefficients on police monitoring are negative and statistically significant.5

Overall, our results indicate that the introduction of surveillance cameras is associated with a significant decrease in crime.

Given the nature of the intervention, our findings should be interpreted as the joint effect of the cameras and the increased presence of police. This is important since a general increased police presence could imply that the effect of the cameras is different from what it would have been without a general increase in police presence. In addition, given that our data are on reported crime, it can be argued that the installation of surveillance cameras may affect the willingness to report crime. If this were the case, and assuming that reporting increases with the installation of surveillance cameras (for example, because victims believe that offenders are more likely to be apprehended), our estimates can be interpreted as lower-bound estimates on the effect of surveillance cameras on crime.

Are the cameras cost-effective?

A simple cost-benefit analysis shows that introducing police-monitored surveillance cameras is a very efficient policy. Government authorities estimate that the total cost of the programme (including cameras, software, and police agents) was about $350,000. As the programme prevents around 35 offences per month (or 420 per year) in monitored areas of Montevideo, the estimated cost for each offence prevented is $830. The Inter-American Development Bank (Jaitman 2017) estimates that the total expenditure on citizen security and crime prevention in Uruguay is 2.2% of GDP (or $1,592 in current US dollars). Given the total number of offences reported per year in Uruguay, the cost incurred by the private sector and the government translates into $4,200 per offence. This is five times higher than the estimated cost per offence prevented with police-monitored surveillance cameras.

Our findings have important policy implications: surveillance cameras seem to be an adequate instrument to keep certain areas of the city with low crime.

References

Armitage, R, G Smyth and K Pease (1999), “Burnley CCTV Evaluation”, in K Painter and N Tilley (eds), Surveillance of Public Space: CCTV, Street Lighting and Crime Prevention, Criminal Justice Press Monsey.

Blixt, M (2003), The Use of Surveillance Cameras for the Purpose of Crime, National Council for Crime Prevention.

Brown, B (1995), “CCTV in Town Centres: Three Case Studies”, Crime Detection and Prevention Series Paper 68.

Ditton, J and E Short (1999), “Yes, It Works, No, It Doesn’t: Comparing the Effects of Open-Street CCTV in Two Adjacent Scottish Town Centres”, in K Painter and N Tilley (eds), Surveillance of Public Space: CCTV, Street Lighting and Crime Prevention, Criminal Justice Press Monsey.

Farrington, D, M Gill, S Waples and J Argomaniz (2007), “The Effects of Closed-Circuit Television on Crime: Meta-Analysis of an English National Quasi-Experimental Multi-Site Evaluation”, Journal of Experimental Criminology 3(1): 21-38.

Gill, M, A Rose, K Collins and M Hemming (2006), “Redeployable CCTV and Drug-Related Crime: A Case of Implementation Failure”, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 13(5): 451-460.

Gómez-Cardona, S, D Mejía and S Tobón (2017), “The Deterrent Effects of Public Surveillance Cameras on Crime”, Documentos CEDE Universidad de los Andes 2017-9.

Griffiths, M (2003), “Town Centre CCTV: An Examination of Crime Reduction in Gillingham, Kent”, Unpublished Dissertation, University of Reading.

Hayes, R and D Downs (2011), “Controlling Retail Theft with CCTV Domes, CCTV Public View Monitors, and Protective Containers: A Randomized Controlled Trial”, Security Journal 24: 237–250.

L. Jaitman (ed.) (2017), The Costs of Crime and Violence: New Evidence and Insights in Latin America and the Caribbean, Inter-American Development Bank.

King, J, D Mulligan and S Raphael (2008), CITRIS Report: The San Francisco Community Safety Camera Program, University of California Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society.

La Vigne, N, S Lowry, J Markman and A Dwyer (2011), Evaluating the Use of Public Surveillance Cameras for Crime Control and Prevention, US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Lim, H and P Wilcox (2016), “Crime-Reduction Effects of Open-Street CCTV: Conditionality Considerations”, Justice Quarterly 34(4): 1-30.

Machin, S and O Marie (2011), “Crime and Police Resources: The Street Crime Initiative”, Journal of the European Economic Association 9: 678- 701.

McLean, S, R Worden and M Kim (2013), “Here’s Looking at You: An Evaluation of Public CCTV Cameras and Their Effects on Crime and Disorder”, Criminal Justice Review 38(3): 303-334.

Munyo, I and M Rossi (2019), “Police-Monitored Cameras and Crime”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Piza, E, J Caplan and L Kennedy (2014), “Is the Punishment More Certain? An Analysis of CCTV Detections and Enforcement”, Justice Quarterly 31(6): 1015-1043.

Priks, M (2014), “Do Surveillance Cameras Affect Unruly Behavior? A Close Look at Grandstands”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 116(4): 1160-1179.

Priks, M (2015), “The Effects of Surveillance Cameras on Crime: Evidence from the Stockholm Subway”, The Economic Journal 125(588): 285-305.

Ratcliffe, J, T Taniguchi and R Taylor (2009), “The Crime Reduction Effects of Public CCTV Cameras: A Multi‐Method Spatial Approach”, Justice Quarterly 26(4): 746-770.

Skinns, D (1998), Doncaster CCTV Surveillance System: Second Annual Report of the Independent Evaluation, Faculty of Business and Professional Studies, Doncaster College.

van Ours, J and B Vollaard (2016), “The Engine Immobilizer: A Non-Starter for Car Thieves,” The Economic Journal 126: 1264-1291.

Welsh, B and D Farrington (2004), “Evidence-Based Crime Prevention: The Effectiveness of CCTV”, Crime Prevention and Community Safety 6(2): 21-33.

Welsh, B and D Farrington (2009), “Public Area CCTV and Crime Prevention: an Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”, Justice Quarterly 26(4): 716-745.

Winge, S and J Knutsson (2003), “An Evaluation of the CCTV Scheme at Oslo Central Railway Station,” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 5(3): 49-59.

Endnotes

[1] Brown (1995), Skinns (1998), Armitage et al. (1999), Ditton and Short (1999), Blixt (2003), Griffiths (2003), Welsch (2004), King et al. (2008), La Vigne et al. (2011), Hayes and Downs (2011), McLean et al. (2013), Piza et al. (2014), Priks (2014), Priks (2015), van Ours and Vollaard (2016) and Gomez-Cardona et al. (2017) find reductions in crime following the installation of surveillance cameras. However, Winge and Knutsson (2003), Gill (2006), Farrington et al. (2007), Ratcliffe et al. (2009) and Lim and Wilcox (2016) find no conclusive results.

[2] Alexandrie (2017) reviews recent studies that rely on random assignment and natural experiments in order to address some of the methodological shortcomings of the previous literature.

[3] Priks (2014) presents evidence that surveillance cameras reduce unruly behaviour inside soccer stadiums. Gomez-Cardona et al. (2017) find that total crime reports are 24% lower within the coverage zone following the installation of a camera relative to the average baseline level of crime reports.

[4] Gómez-Cardona et al. (2017) report no significant effects on apprehensions following the installation of surveillance cameras in Medellín, Colombia. Unfortunately, we cannot formally test the impact of surveillance cameras on apprehension rates because there is no information available.

[5] The fact that most of the impact from the introduction of cameras is on outdoor crime validates the use of outdoor crime to perform the spillover analysis above.