Around the world, the coronavirus pandemic is pushing many firms towards insolvency by dramatically changing consumption patterns and business operations. The first wave of liquidity-focused policy responses in many jurisdictions prevented or delayed more severe consequences for the corporate sector. While some liquidity support is still needed, the crucial issue that must be tackled now is that of corporate solvency.

The corporate solvency problem

A wave of corporate bankruptcies would mean the loss of potentially millions of jobs, accompanied by economic damage, inefficiencies, and spillovers that arise when a company shuts down. Further, the creation of ‘zombie companies’ that do not go bankrupt but are consumed by an excessively heavy debt burden would hamper economic growth, as it was the case in Japan’s infamous Lost Decade (Caballero et al. 2008, Acharya et al. 2009).

Some may be less concerned about future insolvencies, based on the fact that there were fewer insolvencies than feared in the early stages of the recession. However, we believe this fact primarily reflects massive levels of government support, which are unlikely to be maintained at similarly high levels going forward. As support programs taper off, many firms may collapse if governments don’t find other, more tailored solutions. Additionally, many firms have depleted their cash reserves and survived by taking temporary measures that will not be sustainable. Solvency problems are likely to be particularly severe for small and medium-sized firms, which are hit harder than large companies and have fewer financing options available. In many countries, roughly a fifth of firms may experience serious financial distress under adverse pandemic scenarios with continued lockdown measures (Oliver Wyman 2020).1 Resulting increases in non-performing loans (NPLs) present a risk of harmful spillovers to the financial sector. This risk should be managed proactively.

The challenge now lies in designing new policies that address the shortcomings of the initial policy response. These shortcomings include:

- inadequate targeting of support depending on the situations of different firms

- excessive focus on credit provision, overburdening firms with debt and using resources inefficiently

- suboptimal use of private sector expertise, and excessive direct government intervention and

- an unsustainable level of public spending as the crisis persists.

Responding to corporate solvency problems

In our recent report for the Group of Thirty (Group of Thirty 2020), we recommend three devices to support policymakers in addressing this solvency challenge:

- a set of principles that should guide policymakers as they tackle this crisis

- a kit of policy tools appropriate to this challenge and

- a detailed decision-making framework for officials to determine how to best use these tools.

This actionable framework should support the development of policy responses that reflect the specific pandemic context, resources and institutions, economic and political systems, and societal values in individual jurisdictions.

Guiding principles

Policymakers should be guided in their responses by a set of principles. Four such critical principles are set out below.

First, we must shift the focus from the liquidity challenge to the solvency challenge. In their initial responses to the pandemic, governments ensured that most companies had ready access to large amounts of new loans to tide them over the immediate problems. However, in the long run, piling additional debt onto companies with financial problems is not sustainable. Instead, we need to encourage new investments into these companies or facilitate the conversion of some of the debt into equity.

Second, government responses to the corporate problems must be targeted. There are limited resources, which must be offered only to companies that are viable in the long-term and that need assistance that the markets would not provide on their own. Firms that will ultimately fail or be zombies for many years should not be aided, although their employees should be helped. At the other end of the spectrum, strong firms or those that can sell shares in the market do not need assistance.

Third, assistance should be targeted with an eye to the economy of the future, not the economy from before the pandemic. It would be wasteful to attempt to stop some of the changes that were accelerated by the pandemic. In some cases, this will mean letting firms close if their business models will not work in the future (Hodbod et al. 2020).

Fourth, governments should, as far as possible, use the private sector to tackle this challenge. In many countries, private sector investors can take much of the burden, with appropriate guidance and government incentives. Further, the private sector has the necessary expertise to distinguish viable companies from ones that are likely to fail and they face fewer political constraints when allocating investments.

The policy toolkit

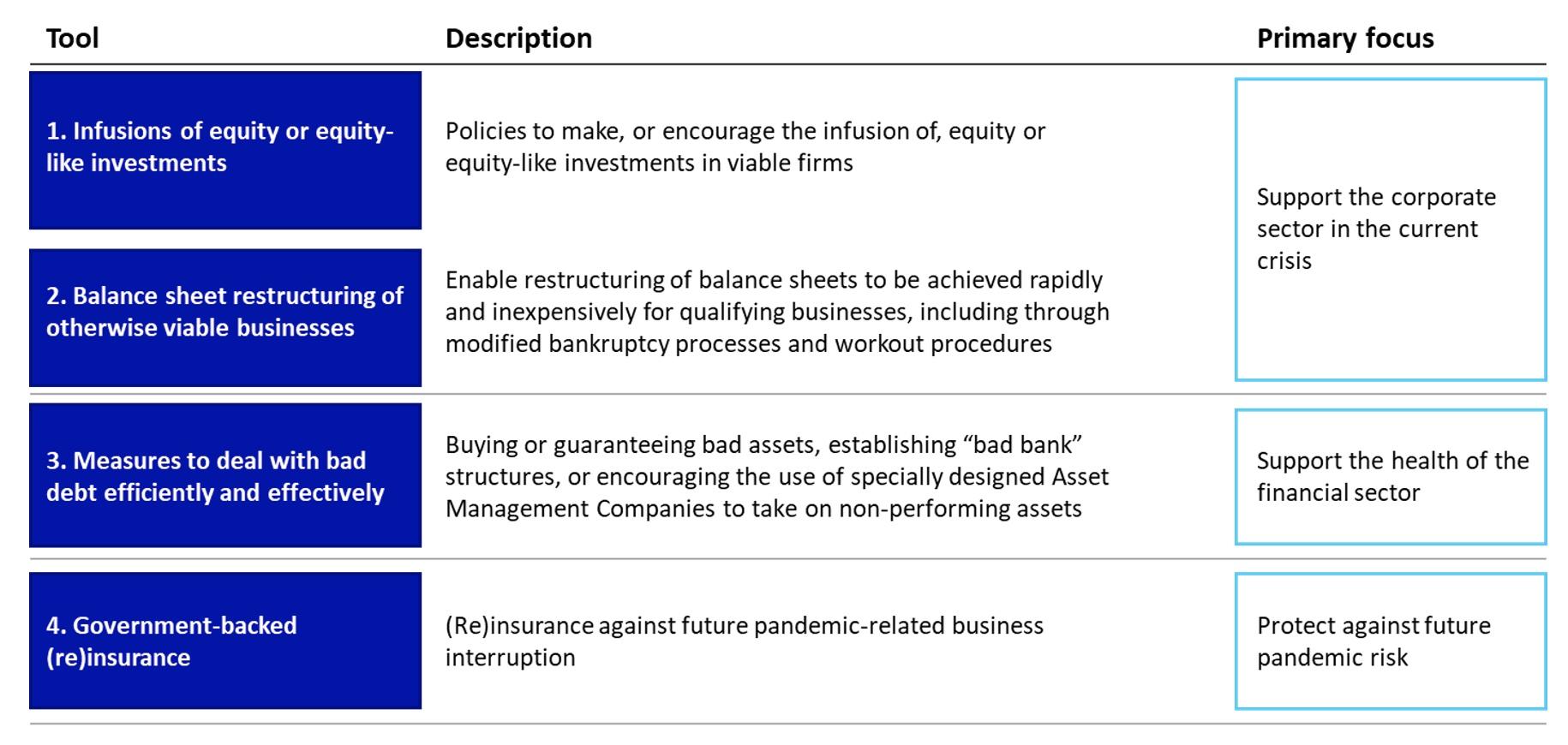

We recommend that officials draw from four buckets of policy tools when responding to the corporate solvency problem and its effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Policy tool kit

The first bucket involves encouraging new investments in firms, through purchases of common stock or, in most cases, various forms of quasi-equity. These may take the form of preferred shares, loans with warrants or profit participation rights, or even government grants in exchange for higher future tax rates on profits earned by companies that have been assisted (e.g. Blanchard et al. 2020). In all cases, the point is to increase a firm’s financial resources without adding debt.

Our call for use of equity and equity-like financing acknowledges the worldwide acceleration in growth of private patient capital over the last decade. This includes private equity and private debt funds, but also direct investment by large institutional investors with capital and structuring expertise, including pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. Ideally, markets would deliver equity capital without government intervention; however, if private markets fail to mobilize the rescue capital on acceptable terms, government action may be required. There are multiple ways governments could incentivize private investors to put up most or all of the funds, such as by offering tax incentives or periodic cash payments.

The second bucket focuses on converting existing debt into equity at troubled firms. Bankruptcy processes can do this, but in most countries existing bankruptcy laws are poorly suited to handle the challenge at hand. In many countries, this relates to an underlying assumption that any company entering bankruptcy is a bad business. Chapter 11 of the US bankruptcy code is better suited for this crisis, as it assumes that a bankrupt company is usually a sound business with an unsound balance sheet. However, even a bankruptcy law with the right attitude can be excessively expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, we recommend supplementing existing law with mechanisms to encourage fast, voluntary debt-for-equity swaps prior to bankruptcy. The UK, through the 2020 corporate Insolvency and Governance Act (UK Government 2020), and Singapore, through the Simplified Insolvency Program (Ministry of Law Singapore 2020), have both made such reforms in response to Covid-19.

The third bucket deals with the problems that arise when firms become insolvent and saddle the balance sheets of banks with bad debt. There are a variety of measures to reduce the costs for society and ensure that banks can continue to provide the necessary credit to fuel the recovery. These include the possibility of creating specialized asset management companies to handle bad debt, similarly to what Europe is examining now.

The fourth bucket considers government reinsurance of pandemic business interruption insurance. Companies can already purchase insurance against forced time-limited suspensions of their operations but there is virtually always an exclusion for pandemics as this is too big a risk for the insurance industry to bear on its own. Under the current approach, governments end up paying out massive amounts of aid in a crisis such as today’s through ad hoc programs pulled together under severe time pressure and tough political constraints. Instead, in advance of a crisis, governments could encourage insurers to drop their pandemic exclusion in exchange for a promise that governments will be picking up future losses over a certain level through a reinsurance contract (e.g. Marsh 2020).

Putting this into action

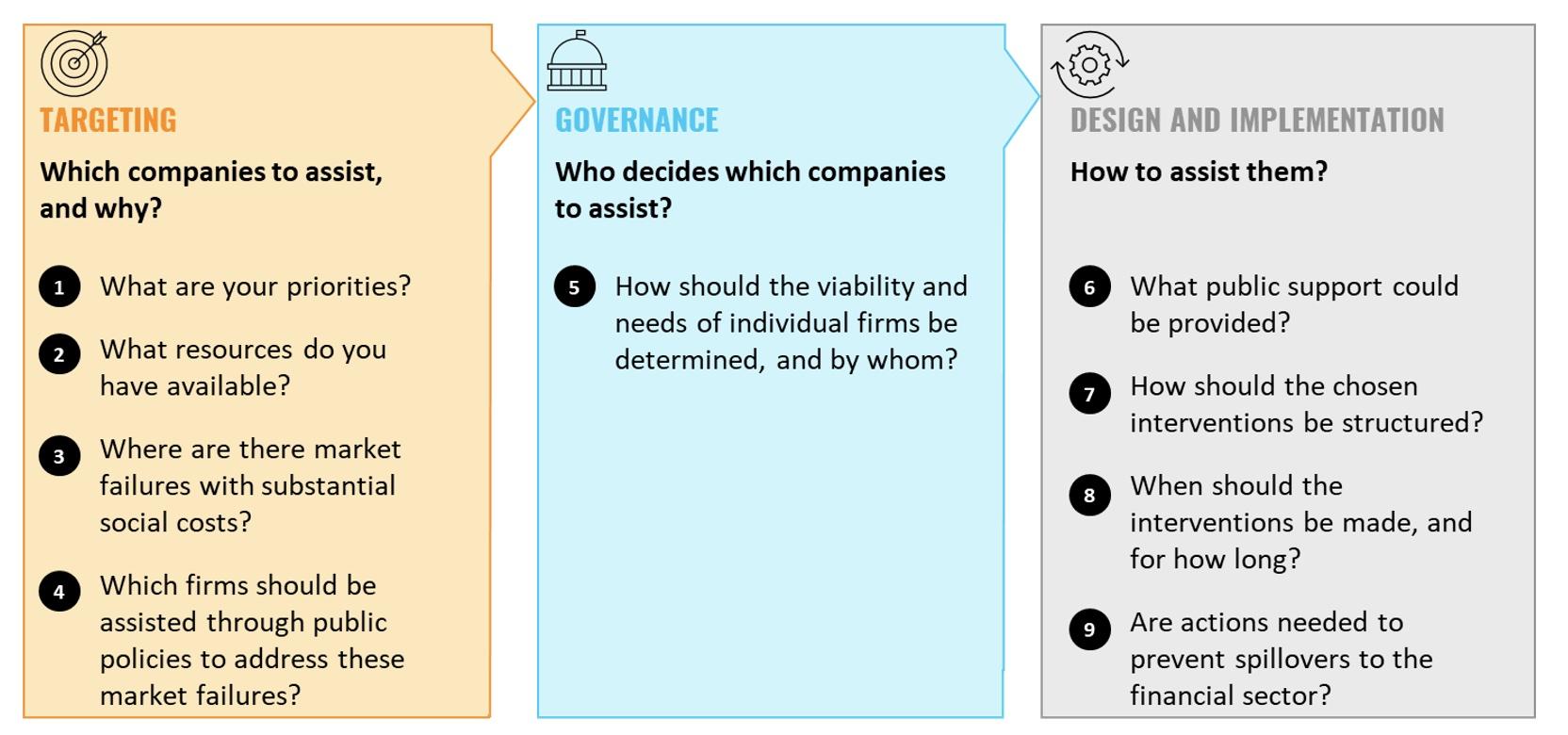

Governments not only differ in the resources they have available, but also in institutional capabilities such as bankruptcy regimes, public development finance institutions, or private sector skills to deal with financial distress. Further, political priorities, for instance the greening of the economy, and public sensitivities, such as attitudes towards nationalization, will also differ. A one-size-fits-all approach is therefore not possible. We hence recommend a decision framework to assist policymakers in choosing the policy tools best fit for their circumstances and how best to implement this responses (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Decision framework (after Group of Thirty 2020)

The year ahead will demand hard decisions of policymakers in many jurisdictions. We hope to provide the practical tools and examples of how they can respond to the corporate solvency problem and prepare their business sectors for growth and resilience once the effects of the pandemic abate.

Authors’ note: This column is based on our recent work with the Group of Thirty’s Working Group on Corporate Sector Revitalization. We would like to thank the members of that Group, in particular the project Co-Chairs, Mario Draghi and Raghuram Rajan.

References

Acharya, V V, M Crosignani, T Eisert and C Eufinger (2009), “Zombie Credit and (Dis-)Inflation: Evidence from Europe”, NBER Working Papers 27158.

Blanchard, O, T Philippon and J Pisani-Ferry (2020), “A New Policy Toolkit Is Needed as Countries Exit COVID-19 Lockdowns”, Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) 20-8, June.

Caballero, R J, T Hoshi and A K Kashya (2008), “Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan”, American Economic Review 98 (5): 1943–1977.

Hodbod, A, C Hommes, S J Hube and I Salle (2020 ),“Avoiding zombification after the COVID-19 consumption game-changer”, VoxEU.org, 21 December.

Group of Thirty (2020), “Reviving and Restructuring the Corporate Sector Post-Covid: Designing Public Policy Interventions”, Group of Thirty, Washington D.C.

Marsh (2020), “Pandemic Risk Protection”, Insights, June.

Ministry of Law Singapore (2020), “Simplified Insolvency Programme,” October 5.

Oliver Wyman (2020), “Building up immunity of the financial sector: Policy actions to address rising credit risk and preserve financial stability”, August.

UK Government (2020), “Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill 2020: factsheets”, UK Government Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and The Insolvency Service, June 1.

Endnotes

1 See particularly analysis on pages 9-11