As the frequency and severity of natural disasters increase, demand is growing for public support for firms suffering from disasters. The Japanese government is among those that have already started to respond to these demands from the private sector. This is partly due to the potential impact local disasters have on the whole economy, which become bigger as a result of economic integration (Acemoglu et al. 2012).

However, the problem is that the reconstruction costs are already so large that government financial conditions tend to deteriorate after disasters (Benali et al. 2018). What’s worse, the cost of disasters for the government is likely to continue growing, considering the increasing frequency and severity of disasters and the political motivations inherent in subsidies (Altay and Ramirez 2010, Garrett and Sobel, 2003). Therefore, it is important to discuss the effective targeting of government support to disaster-hit firms.

De Mel et al. (2012) provide firm-level evidence from Sri Lanka that suggests that a capital subsidy is effective in the retail sector but not in others. They note that more massive disruptions to supply chains in non-retail sectors may be a potential contributor to this difference, yet they do not test this hypothesis due to data limitations. Todo et al. (2015), in contrast, find a positive effect of supply chains on the recovery of disaster-hit firms. Using Japanese supply chain data, they show that having more supply chain partners hastened the recovery of disaster-hit firms. However, their research does not explore the role of public support nor sectoral differences.

My recent work extends these studies and examines the effect of capital subsidies after a great disaster on the recovery of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), focusing on the Japanese SMEs affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake (Kashiwagi 2019). I evaluate the impact of a unique subsidy named the ‘Group Subsidy’, which was first implemented in 2011 and has been repeatedly applied by the Japanese government in the wake of disasters. Regardless of the repeated use, no empirical research yet exists.

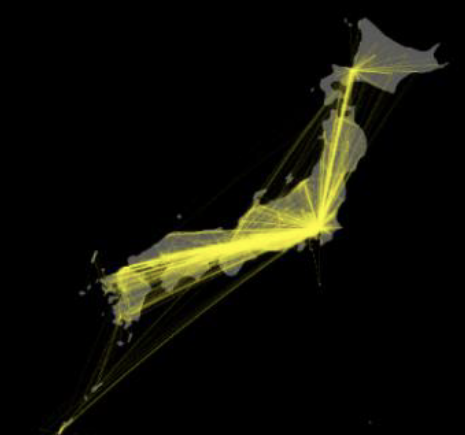

The data used in this study are the list of subsidy-recipient firms and firm-level data of Tokyo Shoko Research. They include supply chain information as well as financial information. I visualise supply chains captured by Tokyo Shoko Research data in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Japanese supply chains

Source: Author

The Group Subsidy

The Group Subsidy is a unique scheme to support SMEs that suffered from natural disasters. It subsidised 75% of the costs to repair or restore the capital goods of SMEs destroyed by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunamis (SME Agency of Japan 2011). The Group Subsidy thus plays a vital role in employment and economic activities in the region.

The Group Subsidy was distinctive in that it was provided not to individual firms, but to groups of firms. The subsidy provider encouraged firms to organise themselves in groups linked by supply chains, location, or industry. This unique feature helped the Japanese government to avoid criticism over the use of public funds to restore the private properties of individual firms. It was designed to give the impression that the money was used not to help individual firms, but to achieve the recovery of the regional economy.

The volume of subsidies provided by this policy is enormous. By 2018, a total of ¥504 billion (approximately $4.6 billion) had been provided to groups of firms damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Effects of the Group Subsidy on the performance of SMEs

I estimated the impact of the Group Subsidy on the post-disaster performance of firms that were directly affected by the disaster using an approach combining propensity score matching and analysis of covariance (PSM-ANCOVA). The method enables me to compare the firms that received the subsidy with those that did not receive it, but that had similar pre-disaster characteristics. Results show that the Group Subsidy was effective in the retail sector but not in the manufacturing or other service sectors, which is consistent with the finding for Sri Lanka in De Mel et al. (2012).

Why was the subsidy effective in the retail sector, but not in the manufacturing or other service sectors? In my paper, I discuss two possible mechanisms. First, disruptions in supply chains may limit the recovery of firms in some sectors, even if the firms themselves successfully restore their facilities. The scale of the disruption damage varies depending on the density of supply chains, and it is bigger with denser networks (Kashiwagi et al. 2018). As retail supply chains tend to be less intense or less complex, the disruptions caused by the supply chain partners might not inhibit the performance recovery of the subsidised retail firms. If this is the case, the difference in the disruption explains the sectoral heterogeneity in the impact of the subsidy on the recovery of firms.

Second, private support from other firms, which was provided five months or more before the subsidy, may have been sufficient for recovery in some sectors. Thus, for them, the impact of the subsidy may have been limited.

A series of econometric analyses reveals that the latter is the more likely reason. My results show that the subsidy quickened the recovery if the firms belonged to the sectors in which supply chains had little recovery effect. In contrast, when having more linkages in or out of the disaster area led to a substantial recovery, the subsidy had no significant impact on the recovery in their performance. Supply chain partners are often the source of private support. Therefore, these results imply that the sectoral difference in the effect of the subsidy arose from variations in the degree of private support across sectors, not from variations in supply chain disruption. Although data limitations prevent me from examining the reasons behind sectoral variations in the degree of private support empirically, the variations probably come from the difference in the criticality of facilities to business continuity. Retail firms rely less on their facilities. Thus, in the short run, even with some damage to their facilities, they can continue operating their businesses without bothering their business partners. Consequently, partner firms, which provide support mainly to avoid the lack of supply or demand, may offer less support to retail firms.

Concluding remarks

Recently, some governments have started to provide post-disaster support to private businesses. One form of support is the Group Subsidy, which Japan introduced in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake. It was initially considered as a one-time policy to get over one of the greatest disasters on record. However, it has been repeatedly applied to this day. My recent research evaluates the new policy scheme Group Subsidy empirically, illustrating which sector should be prioritised in subsidy distribution when a prioritisation is necessary.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Acemoglu, D, V M Carvalho, A Ozdaglar and A Tahbaz-Salehi (2012), "The network origins of aggregate fluctuations", Econometrica 80(5): 1977-2016.

Altay, N and A Ramirez (2010), "Impact of disasters on firms in difference sectors: Implications for supply chains", Journal of Supply Chain Management 46(4): 59-80.

Benali, N, I Abdelkafi and R Feki (2018), "Natural-disaster shocks and government's behavior: Evidence from middle-income countries", International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 27: 1-6.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2012), "Enterprise recovery following natural disasters", The Economic Journal 122(559): 64-91.

Garrett, T A and R S Sobel (2003), "The political economy of FEMA disaster payments", Economic Inquiry 41(3): 496-509.

Kashiwagi, Y (2019), "Postdisaster subsidies for small and medium firms: Insights for effective targeting", ADB Economics Working Paper Series, Asian Development Bank. (previously published as "Enterprise resilience to disasters: Who needs public support?", RIETI Discussion Paper, No. 19-E-029)

Kashiwagi, Y, Y Todo and P Matous (2018), "International propagation of economic shocks through global supply chains", WINPEC Working Paper. Waseda Institute of Political Economy.

SME Agency of Japan (2011), "Chusho Kigyo tou Gurupu Shisetsu tou Hukkyu Seibi Hojo Jigyo ni Tsuite (Report on subsidies for the recovery of facility of groups of small and medium-sized Enterprises)". Retrieved from

Todo, Y, K Nakajima and P Matous (2015), "How do supply chain networks affect the resilience of firms to natural disasters? Evidence from the Great East Japan Earthquake", Journal of Regional Science 55(2): 209-229.