Along with the rise of populist movements, the adoption or encouragement of various measures to combat immigration has been increasing. One popular suggestion is a ‘point system’, whereby potential immigrants are assessed based on a number of criteria, for example age, educational attainment, language, etc. Such systems have already been adopted in Australia and Canada, and have been proposed for example in both the US and the UK.1 Another common bone of contention has been ‘chain migration’, i.e. immigrants coming to a country due to family connections, which in the US constitutes a far larger proportion of total immigration than those entering on green cards. The empirical literature on the impact of immigration is rather mixed, although a number of recent studies have argued that high-skilled immigrants can promote knowledge and technology transfer (Hornung 2014), improve human capital (Kerr and Lincoln 2010, Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010, Moser et al. 2014, Rocha et al. 2017), and impact on growth more generally through patenting (Akcigit et al. 2017a, 2017b).

To a certain extent, the fact that elite migrants foster development is not a surprise, and might even suggest support for policies which discriminate according to skills. The era of mass migration to the US, however, allows us to consider another side to this debate. The majority of those immigrants was arriving from different countries at different points in time. Some of these countries were initially rather poor, but by the end of the 19th century had become considerably richer. This suggests an important potential implication: groups of migrants who might initially seem rather undesirable and would score fewer points, such as poor, rural migrants or refugees from less developed countries, might later turn out to be desirable. If their home country develops – perhaps even overtaking the host country in some respects – and they foster connections with their country of origin, they could facilitate the adoption of new technology or attract future desirable migrants. No previous study has considered this possibility, and we consider an example well-suited to illustrate this point, taken from the history of Danish migration to the US.

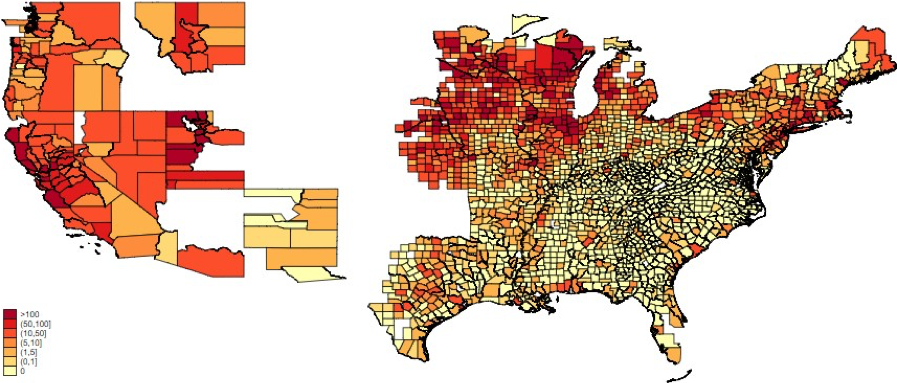

Figure 1 Number of Danes per US county in 1880

In Boberg-Fazlic and Sharp (2019), we demonstrate how the small Danish settlements established in the US before 1880 (see Figure 1) came to play an important role for spreading information on subsequent radical changes that were taking place in Danish agriculture, and dairying in particular. Our hypothesis is that these Danish communities facilitated the spread of information about revolutionary changes in dairying that were taking place at home. Our results show that the areas with more Danes are associated with both a greater specialisation in dairying, and the use of more advanced technologies before WWI. In fact, the association between these areas, which are mostly in the Midwest, and dairying can even be detected after WWII.

Danish agriculture developed rapidly from the 1880s with the emergence of a modern dairy industry. Many consider that the industry was a decisive factor in the country’s catch-up with the richest countries of the time.2 Previous work has demonstrated that these developments rested on innovations introduced by large landowning elites since the 18th century. However, they spread to the peasantry with the invention of a new technology, the automatic cream separator, a steam-powered centrifuge. This new technology allowed for centralisation of production under a new institution, the cooperative creamery (Lampe and Sharp 2018, Jensen et al. 2018). The first of these was founded in 1882, followed by hundreds of others around the country within a decade. Massive increases in productivity followed, production boomed, and Denmark captured a large share of the important UK market for butter and other agricultural products.

Of course, Denmark was, and is, a small country, with a population of fewer than two million around 1880. There was little obvious opportunity for its emigrants to make a large impact on the US. Moreover, in contrast to its Scandinavian neighbours, Norway and Sweden, which witnessed massive outmigration in the 19th century, Danish emigration was relatively modest. Between 1840 and 1914 only 309,000 Danes emigrated, approximately 16% of the population compared to 24% in Sweden and almost 39% in Norway (Hvidt 1960). The main source for our analysis of these migrants is US census data for the years 1870, 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, and 1920, supplemented by Danish police protocols on emigrants (Det Danske Udvandrerarkiv 2018). Our analysis is conducted on the county level.

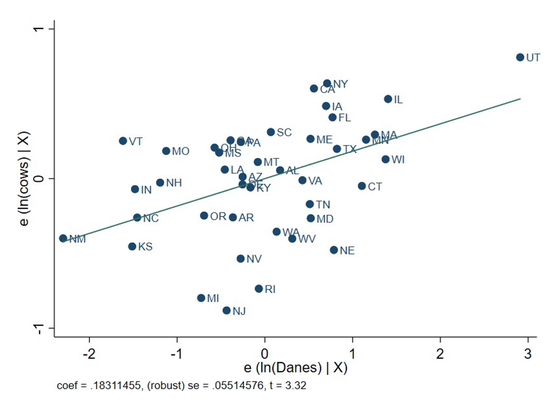

In order to identify the effect of Danish communities on the local dairy industry, we implement a difference-in-differences analysis. We compare the development of the dairy industry in counties that received many Danes with those that received none or only few Danes. Further, we hypothesise that we would see an effect only after 1890. We measure the development of the dairy industry in two different ways. First, we look at whether an area specialised in dairying, by using the number of dairy cows in the county as the outcome variable. Second, we investigate the state of modernisation of the dairy sector, as measured by the number of people working in industrial, and therefore modern, dairying, as well as the amount of butter produced in factories as opposed to farms. For illustrative purposes, Figure 2 shows the partial correlation between the number of Danes in 1900 and the number of dairy cows.

Figure 2 Partial regression plot between ln(Danes) and ln(cows), state level, year 1900

Our hypothesis is that our findings represent primarily a transfer of knowledge. One reason for this is that the absolute number of Danes was simply too small for them alone to have made a difference. Already by 1890 every single Dane in the country would have had to produce more than 1,000 pounds of industrial butter per year if our results were only due to people arriving. Furthermore, we hypothesise that all Danes are potential transmitters of knowledge. Thus, we investigate whether the effect stems from dairy-related Danes more than from other Danes, as we have information on occupation from the Danish emigration data. Moreover, we also investigate whether other immigrant groups also had an impact. Although there is a positive correlation between the number of dairy-related Danes and the number of dairy cows, this does not alter the correlation between other Danes and dairy cows. This is some evidence against a transfer of people or human capital, and in favour of a transfer of knowledge. We also consider the impact of other immigrant groups, but the effect of Danes remains when including all immigrant groups in a horserace specification. It is also the most important in terms of significance and magnitude.

If it was not the flow of people but rather the flow of ideas we are measuring, others must have worked together with Danes or imitated the way Danes were conducting dairying. We therefore also present estimation results using other immigrant groups, but now also including interaction terms between those immigrant groups and Danes. We find a positive interaction effect with Swedes and Norwegians, which makes intuitive sense as these are all first-generation immigrants and thus not likely to be proficient in English. Danes, Swedes and Norwegians would nevertheless understand each other and are also culturally closer to each other than other immigrant groups. It is thus likely that areas receiving both Danes and Swedes or Norwegians would benefit in terms of dairying activity from the interaction between them.

Our findings have important implications for the current debate on immigration. Our results show that it is difficult to determine which immigrants are desirable ex ante and that the host country may benefit from immigration even decades after the first arrival. Concerns similar to today’s were of course also present in the past. Ironically, Cance (1925) unwittingly underlines how difficult it is to know which migrants are desirable. The report was published in the wake of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which established quotas by nationality. He falls into the trap of assuming that previous generations of migrants were the right migrants, specifically mentioning the large number of Scandinavians in agriculture, and concluding that “some of the very best of our farmers are immigrants of the first and second generation”. However, he ends with a warning against importing cheap labour to the countryside. He believed this would hurt rural living standards and delay the process of assimilation, without seemingly realising that discriminating against poor rural migrants would have meant that the Scandinavians he praises would not have arrived in the first place.

References

Akcigit, U, J Grigsby and T Nicholas (2017a), "Immigration and the rise of American ingenuity", American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 107(5): 327–331.

Boberg-Fazlic, N and P Sharp (2019), "Immigrant communities and knowledge spillovers: Danish-Americans and the development of the dairy industry in the United States", CEPR Discussion Paper 13757.

Cance, A (1925), "Immigrants and American agriculture", Journal of Farm Economics 7(1): 102–114.

Det Danske Udvandrerarkiv (2018), Københavns Politis Udvandrerprotokoller (hosted at Danish Demographic Database, delivery 12-02-2018).

Henriksen, I (1993), "The transformation of Danish agriculture 1870–1914", in K G Persson (Ed.), The economic development of Denmark and Norway since 1870, pp. 153–177, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Hornung, E (2014) "Immigration and the diffusion of technology: The Huguenot diaspora in Prussia", American Economic Review 104:(1): 84–122.

Hunt, J and M Gauthier-Loiselle (2010), "How much does immigration boost innovation?" American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2(2): 31–56.

Hvidt, K (1960), Flugten til Amerika, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Jensen, P S, M Lampe, P Sharp and C Skovsgaard (2018), "Getting to Denmark: The role of elites for development", CEPR Discussion Paper 12679.

Kerr, W R and W F Lincoln (2010), "The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and U.S. ethnic invention", Journal of Labor Economics 28(3): 473–508.

Lampe, M and P Sharp (2018), A land of milk and butter: How elites created the modern Danish dairy industry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moser, P, A Voena and F Waldinger (2014), "German Jewish emigres and US invention". American Economic Review 104(10): 3222–55.

Rocha, R, C Ferraz and R Soares (2017), "Human capital persistence and development", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(4): 105–136.

Endnotes

[1] See, for example, https://edition.cnn.com/2017/08/02/politics/cotton-perdue-trump-bill-point-system-merit-based/index.html.

[2] For a brief account, see Henriksen (1993).