The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered an unprecedented deployment of anti-contagion policies throughout the world, among which mobility restrictions feature prominently. Recent studies suggest that adherence to stay-at-home orders is limited among poor households, who typically face acute food shortage and must seek out income generating activities. These studies tend to focus on low- and middle-income countries (Bargain and Aminjonov 2021, Benett 2021, Carlitz and Makhura 2021, Durizzo et al. 2021), but evidence also exists for rich countries.1 While strict containment is difficult to achieve when people must continue to work, a new role is emerging for income support: by enabling people to effectively stay home, it can produce substantial health externalities.

In our new research (Aminjonov et al. 2021), we first confirm that in low- and middle-income countries, regions with a higher incidence of poverty are characterised by a significantly lower reduction in work-related mobility when shelter-in-place policies are enacted – i.e. lower compliance with these containment measures. We then demonstrate that income support schemes have enabled the poor to isolate themselves almost as much as those from lower-poverty incidence regions. Ultimately, these programmes reduce by half the additional contagion caused – via the mobility channel – by regional differences in poverty incidence.

How containment measures and poverty affect human mobility

To assess the effect of poverty on human mobility, we rely on pre-pandemic estimates of poverty incidence for 729 subnational regions across 43 countries in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, as collected from official statistics or estimated using household surveys. These data are merged with daily regional mobility estimates from Google Covid-19 Mobility Reports over 202 days (from 15 February 2020 to 3 September 2020). Daily variation in containment measures is obtained from the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) (Hale et al. 2020). High mobility to workplaces in time of lockdown is interpreted as a low degree of self-protection or a limited compliance with these containment policies.

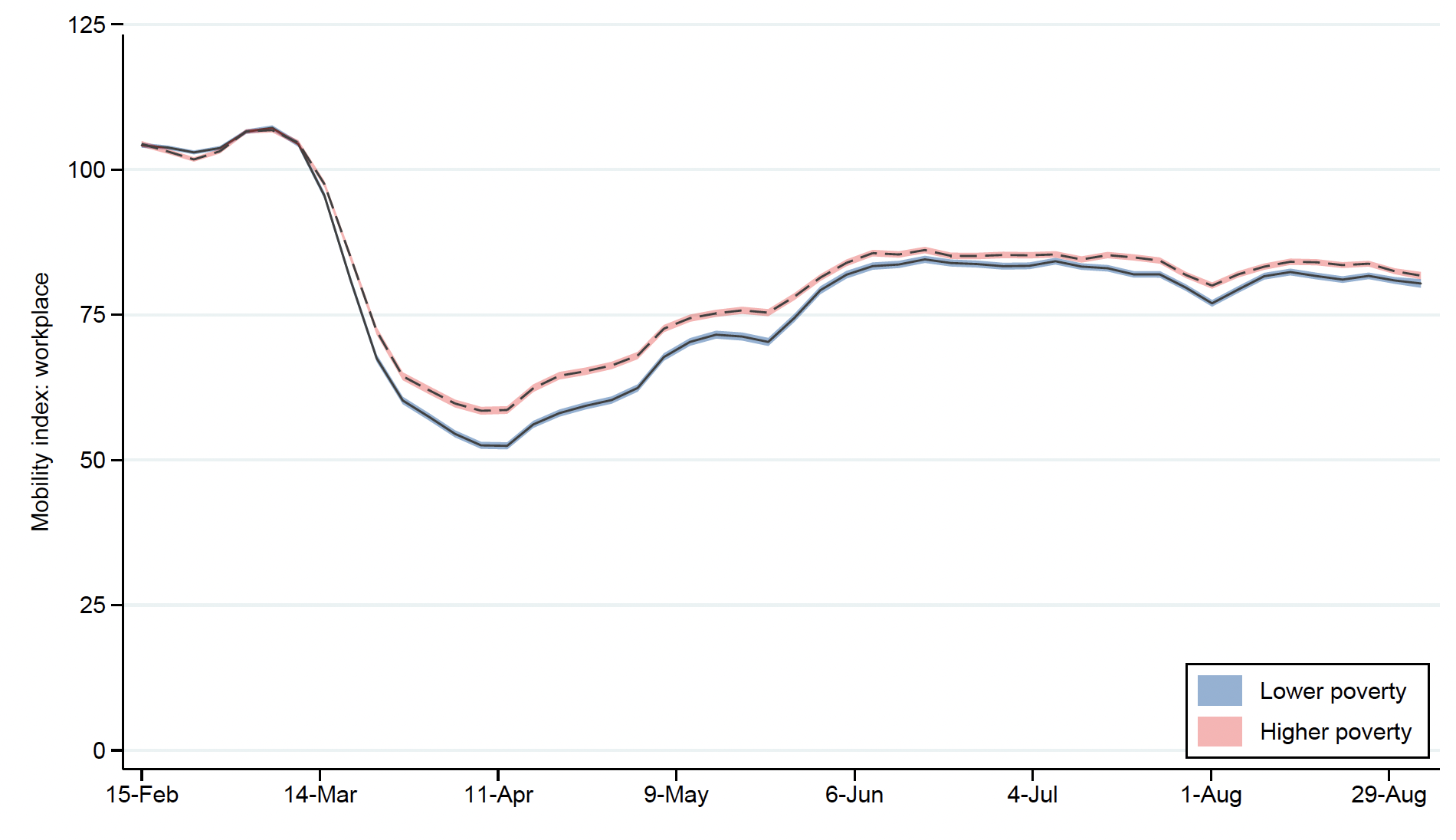

Figure 1 Mobility to workplace by level of regional poverty

Source: author's calculations based on Google mobility data (mobility for workplace), poverty data from national statistics offices and authors' estimations using household surveys, and OxCGRT data on COVID-19 income support.

Notes: Local polynomial fit with 95% CI of daily mobility across regions, weighted by (1/# of regions in the corresponding country). Poverty is measured as the share of people living below national or international poverty lines in a subnational region. Poverty is defined as lower (higher) if region's poverty rate is below (above) global median poverty rate based on the sample of 729 regions across 43 countries.

Figure 1 illustrates the trends in average regional mobility to workplaces for the period under study, differentiating between lower-poverty (below median) and higher-poverty (above median) regions. Mobility fluctuates around 100 in late-February and early-March – i.e. around the same level as in the baseline period of the Google Mobility Reports. Before mid-March, both groups of regions exhibit similar trends and almost no difference in levels. In the following weeks, many governments started to call for physical distancing, which shows up as a sharp drop in work-related mobility. This drop is significantly more pronounced for lower-poverty regions than higher-poverty ones.

The graphical evidence above is confirmed formally using a difference-in-difference estimation of mobility on poverty interacted with daily variation in lockdown status (with no containment in the early period) and controlling for region fixed effects. This simple approach compares the effect of shelter-in-place measures on work-mobility between lower- and higher-poverty regions. With lockdowns, work-related mobility drops everywhere (as shown on the previous figure). However, estimates show that this reduction is around 50% smaller in regions of higher poverty incidence. This difference is interpreted as a higher propensity to continue labour activities in these regions. This is consistent with the fact that such a mobility gap is not found for other types of activity (and, in particular, for necessities such as going to the supermarket or pharmacy).

The effect of emergency income support on mobility

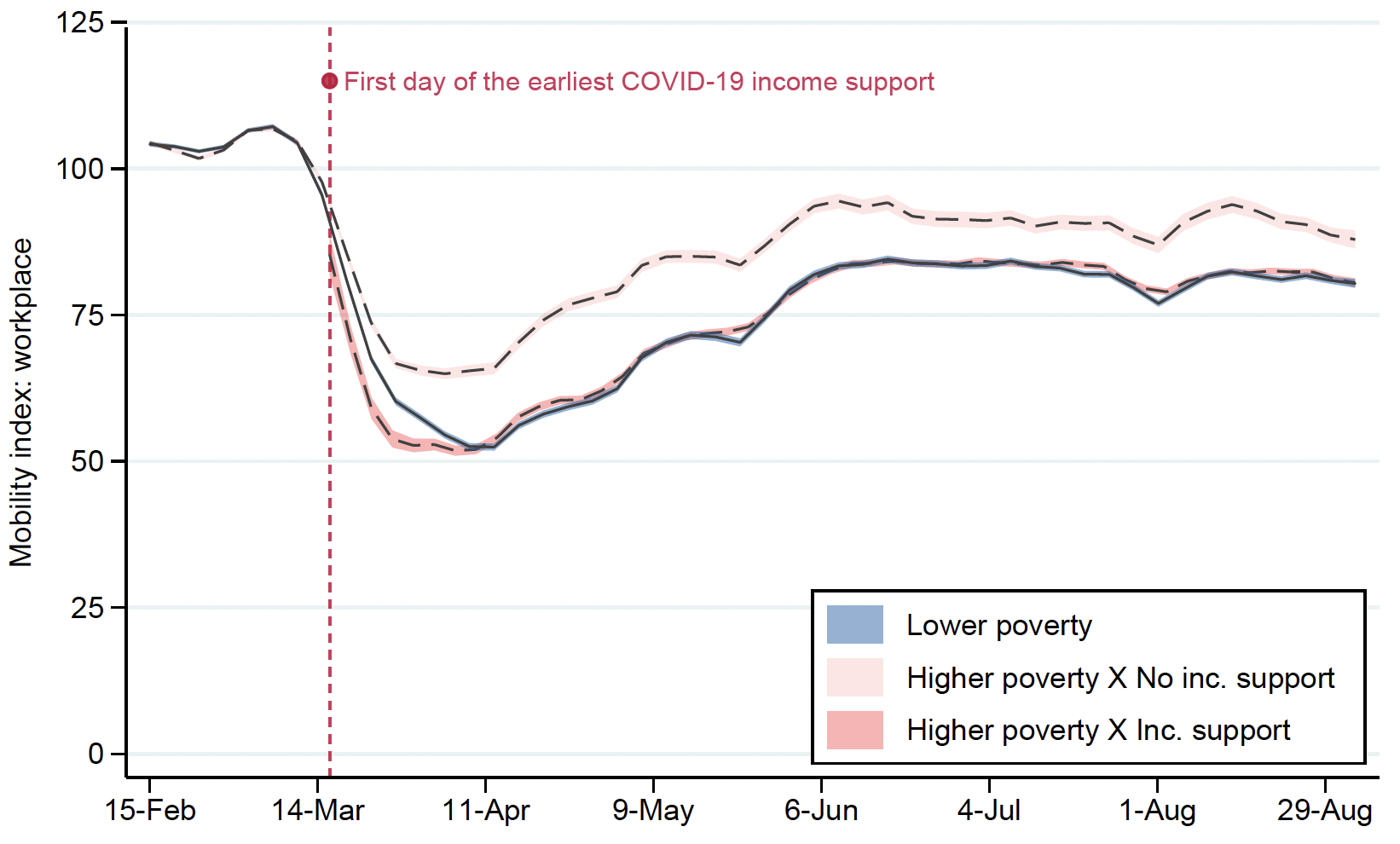

Along with mobility restrictions, governments in low-income countries have engaged in outstanding income support policies. About one-third of all emergency social protection measures took the form of cash transfers, which reached over 1.1 billion people (14% of the world’s population). Usually motivated as a means of preserving livelihoods and avoiding sharp increases in extreme poverty, income support has another function: to help poor populations comply with public health rules, and thus contain Covid-19. We elicit this role using the OxCGRT data tracking national-level daily changes in income support provided to those who cannot work or lost their job due to the pandemic. Figure 2 depicts trends of regional mobility to workplace. The earliest Covid-19 income support programme began on 16 March 2020 and in a few weeks, 75% of the countries under study had implemented some support. Consistently, the figure shows that the drop in mobility is very similar between lower-poverty regions and higher-poverty regions that benefit from income support. The reduction in mobility is much less for poor regions without income assistance.

Figure 2 Mobility to workplace by regional poverty, with or without COVID-19 income support

Source: author's calculations based on Google mobility data (mobility for workplace), poverty data from national statistics offices and authors' estimations using household surveys, and OxCGRT data on COVID-19 income support.

Notes: Local polynomial fit with 95% CI of daily mobility across regions, weighted by (1/# of regions in the corresponding country). Poverty is measured as the share of people living below national or international poverty lines in a subnational region. Poverty is defined as lower (higher) if region's poverty rate is below (above) global median poverty rate based on the sample of 729 regions across 43 countries. COVID-19 income support shows the daily status of whether government provides any income support to those who cannot work or lost their job due to the COVID-19 pandemic (country-day variation in income support).

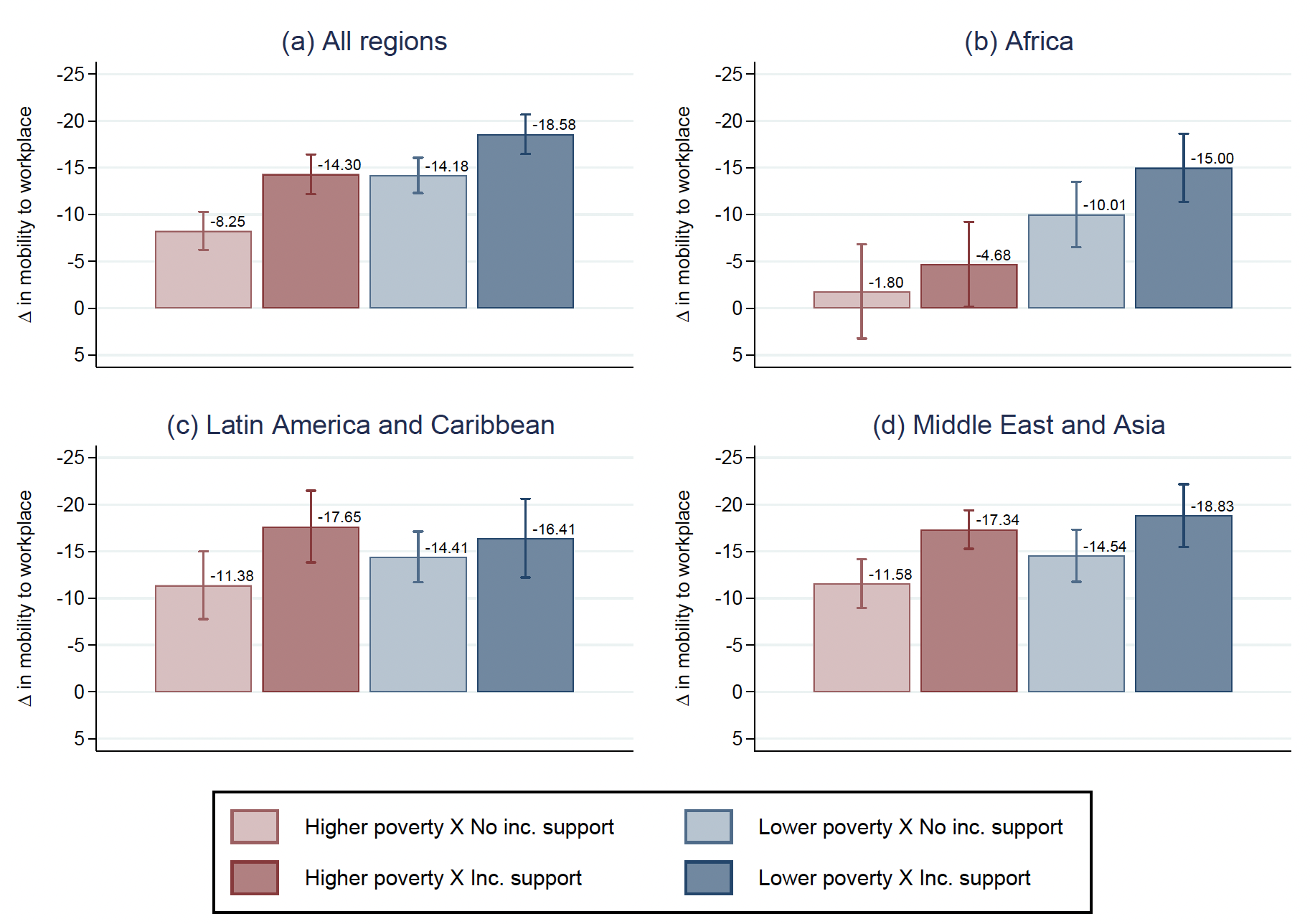

This result suggests that outstanding social protection schemes have helped to improve compliance with containment rules by reducing human mobility. It is confirmed by difference-in-difference estimations with region fixed effects, along with interactions of poverty, lockdown, and income support dummies. Figure 3(a) reports estimates: lockdowns alone reduce mobility by 14.2 points in lower-poverty regions (light blue) and by 8.2 in higher-poverty regions (pink) on average over the period. The complete policy mix (i.e. containment with income support) yields a mobility decline of 18.6 points in lower-poverty regions (dark blue) and 14.3 in higher-poverty regions (red). The main message is that providing income support to people living in the poorest regions helps them to achieve the same mobility reduction as other regions when there is no support. When both types of regions receive transfers, only a small compliance gap persists (4.3 points or 23% of the total mobility decline among the less poor). These findings emphasise the health externalities of social protection for poor people who must leave their home to maintain livelihoods during the pandemic despite containment rules and higher risks of contagion.

Figure 3 Mobility reduction due to stay-at-home orders combined with COVID-19 income support, by poverty level

Source: authors' estimation using Google reports for workplace mobility, regional poverty rates (from national statistics or authors' estimations as described in Table A1) and the information on COVID-19 policy response from OxCGRT for the period February 15 - September 3, 2020.

Notes: Graphs show the mobility effects of stay-at-home orders with and without income support, as compared to the level of mobility during the period without stay-at-home orders and income support policy. Stay-at-Home is a dummy indicating the period in which national stay-at-home orders (recommendations or requirements) are in force. Income support is a dummy indicating period in which any income support is provided to those who cannot work or lost their jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Poverty is defined as lower (higher) if region's poverty rate is below (above) median poverty rate based on the sample of regions within a continent/group of countries. Regressions control for region and day fixed effects, lagged cumulative number of COVID-19 cases (the data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) and reweight observations by 1 over the # of regions in the corresponding country. Capped spikes illustrate 95% confidence interval based on standard errors that are clustered at region level.

The rest of Figure 3 shows some differences across geographical areas. Mobility reduction is low in Africa, possibly given lower living standards than in other continents and the nature of labour markets. Income support in African many countries does not manage to fill the mobility gap across regions and hardly affects the mobility reduction of the very poor. Indeed, the coverage is weak (i.e. new transfers reach less than 10% of the population in a majority of countries) and the overall expenses on emergency social protection are small – $8.3 billion (0.4% of the African GDP) over the year 2020 (Gentilini et al. 2020). For Latin America, we see that mobility gaps due to poverty are much more attenuated (light blue versus pink), with large mobility reduction due to containment measures in all type of regions.2 Nonetheless, for the higher-poverty regions in Latin American countries, the mobility difference due to emergency income support programmes is significant and consistent with the redistributive effort – $52 billion (1.2% of the continent’s GDP, and an average transfer of $154 per capita over 2020).

Implications for the spread of Covid-19

We complete previous results with an estimation of the contagion spread on human mobility. Combined with the estimate relating mobility to poverty and income support, we obtain an assessment of how the virus diffusion rate varies with poverty and income support via increased workplace mobility. A one standard deviation difference in poverty rates between regions results in 25% more Covid-19 cases after five months. This difference is limited to 11% when income support is provided.

The spread of Covid-19 and consequent restrictions on economic activity, notably through containment policies, pose a serious threat to the livelihoods of many of the most vulnerable families on the planet. Governments have responded to this with an unprecedented expansion of their social protection programmes and new transfers. Admittedly, government assistance was insufficient to sustain pre-crisis living standards and to prevent a sharp increase in food insecurity (Egger et al. 2021). Yet, we show that emergency support provided in response to the pandemic has substantially helped to reduce the exposure of the poor to the virus itself. A lot remains to be done in places where the intensity of support is low, notably in Africa where the average expenditure per capita was only $10 in 2020 (Gentilini et al. 2020). Further research will also have to provide more fine-grained information on policy options and their relative effectiveness in terms of health externalities.

References

Aminjonov, U, O Bargain and T Bernard (2021), “Gimme Shelter. Social distancing and Income Support in times of Pandemic”, Bordeaux Economics Working Papers 2021-12.

Bargain, O and U Aminjonov (2021), “Poverty and COVID-19 in Africa and Latin America”, World Development 142: 105422.

Bennett, M, (2021), “All things equal? Heterogeneity in policy effectiveness against COVID-19 spread in Chile”, World Development 137: 105208.

Carlitz, R D and M N Makhura (2020), “Life under lockdown: Illustrating tradeoffs in South Africa’s response to COVID-19”, World Development 137: 105168.

Durizzo, K, E Asiedu, A Van der Merwe, A Van Niekerk and I Guenther (2021), “Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in poor urban neighborhoods: The case of Accra and Johannesburg”, World Development 137: 105175.

Egger, D, E Miguel, S Warren, A Shenoy, E Collins, D Karlan, D Parkerson, A M Mobarak, G Fink, C Udry, M Walker, J Haushofer, M Larreboure, S Athey, P Lopez-Pena, S Benhachmi, M Humphreys, L Lowe, N Meriggi and C Vernot (2021), “Falling living standards during the COVID-19 crisis: Quantitative evidence from nine developing countries”, Science Advances 7.

Gentilini, U, M Almenfi, P Dale, A V Lopez and U Zafar (2020), “Global Database on Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19”, World Bank.

Google (2020), “Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports”, 17 July 2020.

Hale, T, N Angrist, E Cameron-Blake, L Hallas, B Kira, S Majumdar, A Petherick, T Phillips, H Tatlow, S Webster (2020), “Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker”, Blavatnik School of Government.

Papageorge, N W, M V Zahn, M Belot, E van den Broek-Altenburg, S Choi, J C Jamison and E Tripodi (2020), “Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with Self-Protecting Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic”, IZA Discussion Paper 13333.

Endnotes

1 Wright et al. (2020) show that US counties with lower levels of per-capita income record lower levels of compliance with stay-at-home orders. In new data for several Western countries, Papageorge et al. (2020) also find that people with lower income and an inability to tele-work were less likely to engage in behaviors that limit the spread of the disease.

2 These results are more contrasted, and aligned with the global picture, when Brazil is removed from the sample.