The issue of how to select the most appropriate policies to reduce inequalities has attracted considerable interest in both academia and the public debate, particularly in light of the significant increase in inequality documented over the last decades in many countries. However, despite numerous research efforts, comparable long-term estimates of redistributive policies remain deceptively scarce.

Public policies aiming to reduce inequalities can be classified into two categories. First, for a given level of pre-tax inequality, taxes, transfers and other public spending can reduce post-tax income inequality. This are usually called redistribution policies. The public economics literature has largely been influenced by an approach that treats pre-tax inequalities as given and where the policy options for reducing inequalities largely rest on various combinations of taxes and transfers, with the constraints imposed by the behavioural responses to the tax and transfer system (e.g. this is the generic logic of optimal taxation literature). However, public policies can also affect the pre-tax distribution of income – what we call ‘pre-distribution’. A long-lasting literature has advanced several factors explaining pre-tax income inequality. It has typically discussed the relative role of education policies (Katz and Murphy 1992, Chetty et al. 2017), minimum wages (Autor et al. 2016), compensation bargaining (Piketty et al. 2014), international trade, and technological change (Autor et al. 2014, Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020) as driving forces of inequality. Finally, taxation and transfers can also affect pre-tax income either via changes in bargaining incentives or through different dynamics of capital accumulation. Although these channels are known to impact inequalities, the lack of adequate data series with sufficient historical and comparative breadth has limited the ability to evaluate and compare the long-term impact of various public policy options on inequality.

What is the impact of public policies on inequality? What are the relative magnitudes of ‘redistribution’ and changes in pre-tax income in accounting for the observed evolution of inequality over time and across countries? Our new paper (Bozio et al. 2020) breaks new grounds on this issue at both the methodological and substantive level.

From a methodological perspective, we construct historical series of post-tax income for France since 1900. These series are obtained by combining national accounts, administrative tax data, and household survey data in a comprehensive and consistent manner. We develop a microsimulation model and use explicit tax incidence assumptions to impute all taxes, transfers and collective expenditures. As a result, our French post-tax income series are annual, fully consistent with macroeconomic aggregates, and cover the entire income distribution from the bottom to the top percentiles.

On the substantive ground, our objective is to better understand the differential impact of public policies on inequality over time and across countries. To exploit cross-country differences in pre- and post-tax inequalities, we compare our French inequality series1 with those from Piketty et al. (2018) for the US.2 We develop simple statistics to quantify the contribution of redistribution, as opposed to pre-distribution or any other external shocks, in explaining observed long-run trends in inequalities across times and countries.

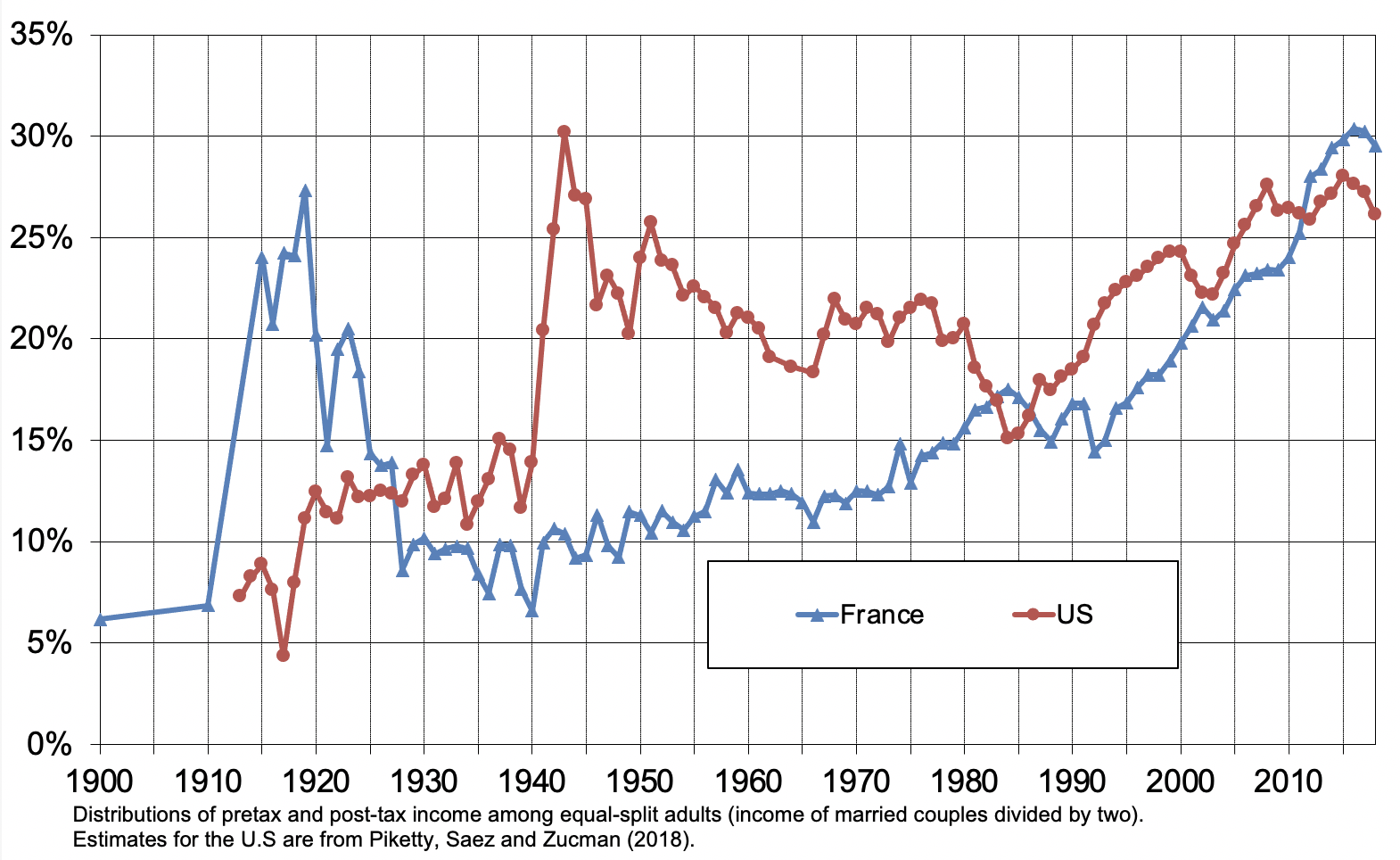

The long-run evolution of pre-tax and post-tax income inequality: France versus the US

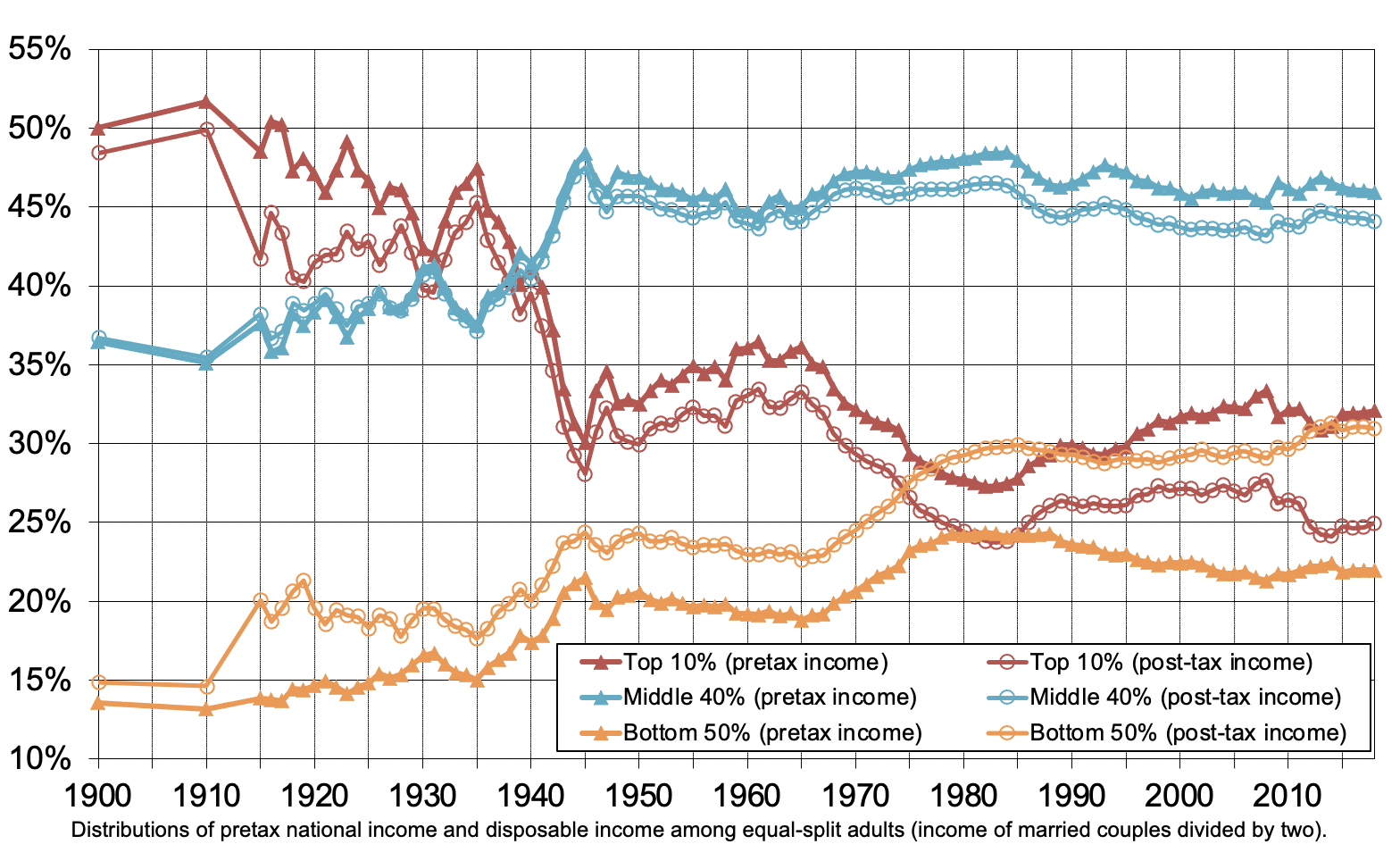

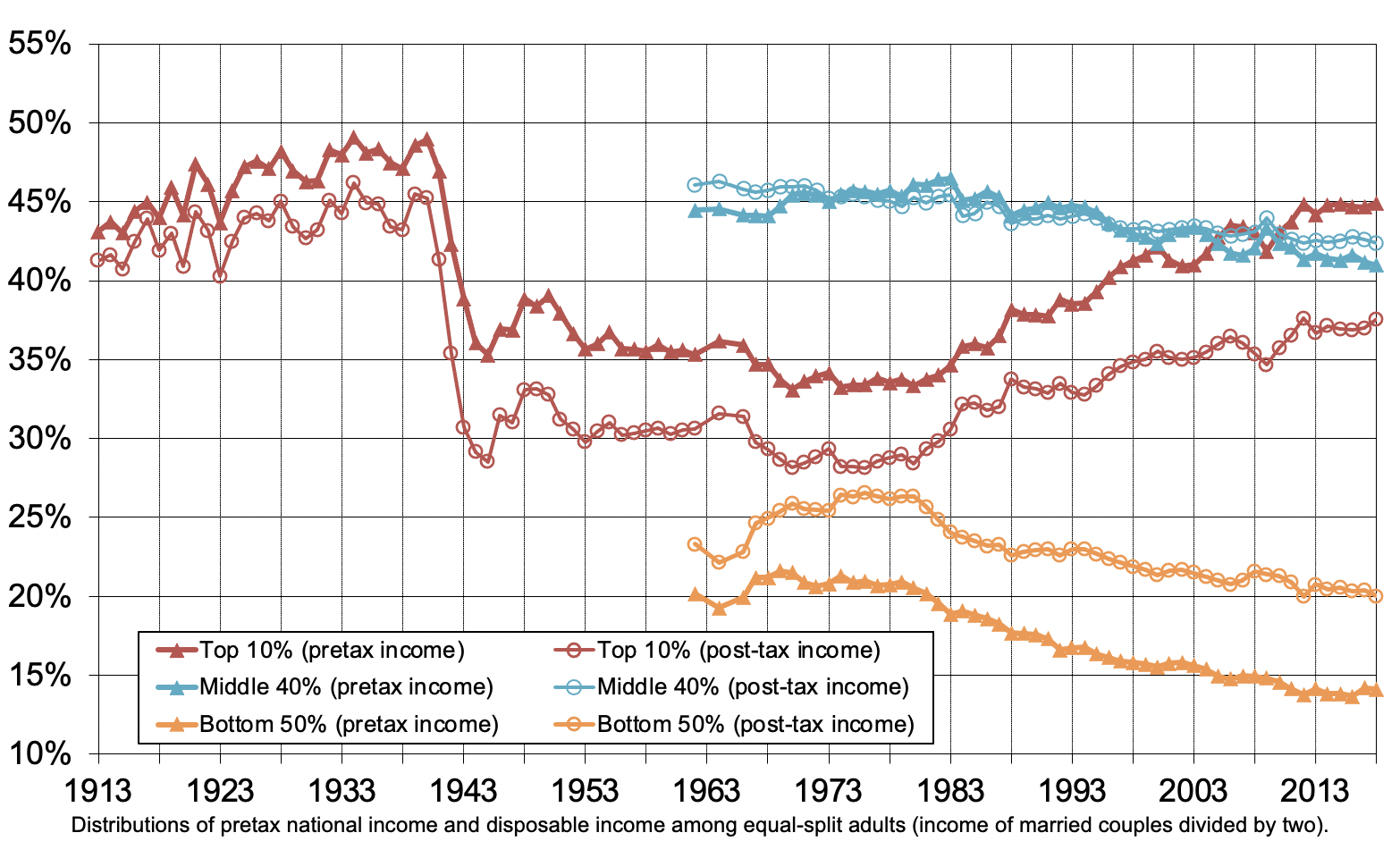

Figure 1 compares the evolution of pre-tax and post-tax income inequality in France (Panel A) and in the US (Panel B) over the 1900-2018 period. Pre-tax income is equal to the sum of all income flows going to labour and capital, after taking into account the operation of the pension and unemployment insurance systems, but before taking into account other taxes and transfers. Post-tax income is defined as pre-tax income minus all taxes plus all monetary transfers, in-kind transfers, and collective expenditures.

Figure 1 Pre-tax vs post-tax income inequality, 1900-2018

a) France, 1900-2018

b) United States, 1913-2018

Two stylised facts are worth highlighting from these series.

- First, the evolution of pre-tax and post-tax income inequality has been far from steady and differs strongly between the two countries. While pre-tax inequality has followed a U-shaped pattern in both countries, post-tax inequality is L-shaped in France and U-shaped in the US. The increasing progressivity of the French tax and transfer system has been able to counteract the gradual rise in pre-tax income inequality, leading to a relatively constant level of post-tax income inequality since the early 1980s. This contrasts strongly with the US case, where rising redistribution has not matched the dramatic increase in pre-tax inequality.

- Second, the difference between pre-tax and post-tax affects mostly the top 10% and bottom 50% income shares in both countries, leaving the middle 40% share almost unchanged.

How much does redistribution reduce inequality over time?

To quantify the impact of redistribution on inequality dynamics, we rely on two main inequality indicators defined either as the ratio between average incomes of the top 10% and bottom 50% groups (ratio T10/B50) or as the ratio between average incomes of the top 10% and bottom 90% groups (ratio T10/B90). In terms of pre-tax income, over 2010-2018 period, the T10/B50 ratio is equal to 7 in France (i.e. on average, the top 10% income earners make seven times more than bottom 50% income earners) compared to a T10/B50 ratio of 16 in the US. In terms of post-tax income, this ratio is reduced to 4 in France (i.e. a reduction of 44%) compared to 9 in the US (i.e. a reduction of 43%). In that sense, one can say that redistribution reduced pre-tax inequality by 44% in France against 43% in the US over the 2010-2018 period.3 When using the alternative T10/B90 indicator, the level of redistribution is lower but still remarkably close for both countries (-27%).

These indicators highlight that France and the US carried out very similar levels of redistribution in 2010-2018, despite very different policies and institutions. Consequently, the much lower level of post-tax inequality in France is not the result of higher redistribution, but almost entirely due to much higher level of pre-tax inequality.

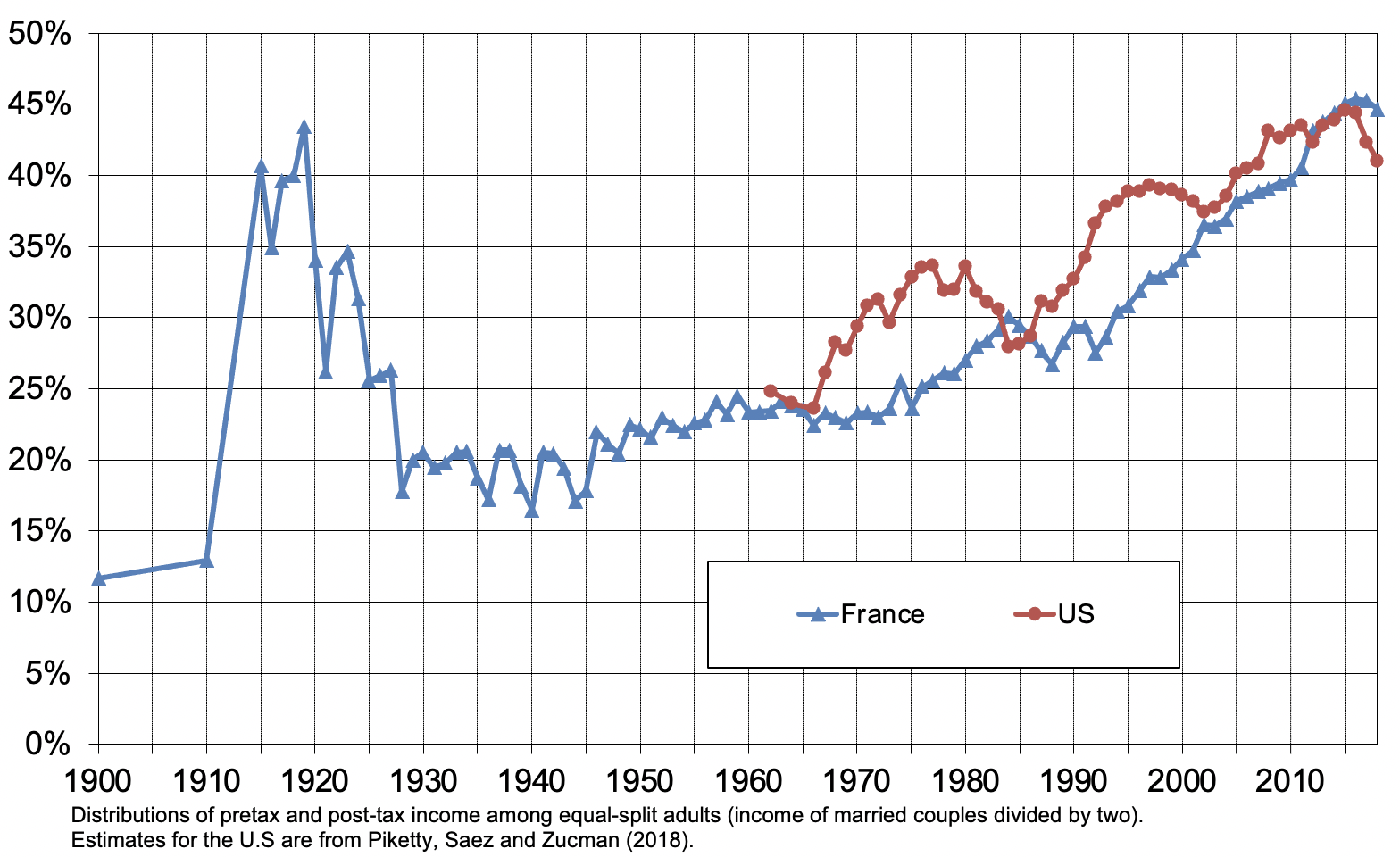

Figure 2 presents the reduction of inequality implied by redistribution in both countries over time. It shows how redistribution had been increasing throughout the entire 20th century, though not at the same pace or in the same period. Redistribution was similar in France and the US just before WWI. It increased noticeably in the US after WWII while France maintained a similar level of redistribution. From the mid-1970s onwards, redistribution increased in France, which caught up with the US. Both countries then experienced increasing redistribution and reached similar levels at the end of the period (2010-2018).

Figure 2 Extent of redistribution in France vs the US, 1900-2018

a) T10/B50

b) T10/B90

In our paper, we develop a simple formula that allows us to decompose the long-term evolution of post-tax income inequality between the variation in pre-tax income inequality and the change in redistribution over time. We show that if post-tax inequality decreased much more in France than in the US during the 1900-2018 period, this was not due to a relatively more significant increase in redistribution in France. The major factor behind this differential trend comes from the differential evolution of pre-tax income inequality between the two countries. Pre-tax income inequality decreased relatively more in France than in the US over the 1900-1983 period and increased relatively less after 1983. Both changes in pre-tax inequality and redistribution have had a significant impact on the historical reduction of inequality, but the former is quantitatively about three times as large as the latter.

From redistribution to pre-distribution?

To summarise our main results, pre-tax income inequality appears to be the main factor accounting for the differential levels and trends in inequality between France and the US over the 20th century.

An inadequate takeaway would be that the non-monetary transfers (e.g. education spending, public goods) have only a very small impact on the evolution of inequality within a country or on the differences in inequality across countries. We believe, however, that our analysis highlights that a large set of policies can affect pre-tax inequality (within country and over time) that would not be captured by the usual concept of redistribution because this analytical tool can only capture direct redistribution from a given pre-tax income inequality. In capturing redistribution, it misses ‘pre-distribution’.

This implies that research and policy discussions should, in the future, focus on pre-distribution as much as on redistribution. In particular, greater attention should be devoted to the study of the various policies and rules that can account for the fact that pre-tax inequality is so much larger in the US than in France.

References

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2020), “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets”, Journal of Political Economy 128(6): 2188-2244.

Alvaredo, F, A B Atkinson, T Blanchet, L Chancel, L Bauluz, M Fisher-Post, I Flores, B Garbinti, J Goupille-Lebret, C Martínez-Toledano, M Morgan, T Neef, T Piketty, A-S Robilliard, E Saez, L Yang and G and Zucman (2020), “Distributional National Accounts Guidelines, Methods and Concepts Used in the World Inequality Database”, WIL WP.

Autor, D H, D Dorn, G Hanson and J Song (2014), “Trade Adjustment: Worker Level Evidence”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4): 1799–1860.

Autor, D H, A Manning and C L Smith (2016), "The Contribution of the Minimum Wage to US Wage Inequality over Three Decades: A Reassessment", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8 (1): 58-99.

Bozio, A, Garbinti, B., Goupille-Lebret, J., Guillot, M. and Piketty, T. (2020), “Predistribution vs. Redistribution: Evidence from France and the U.S.”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15415.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman, E Saez, N Turner and D Yagan (2017), “Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility”, NBER Working Paper 23618.

Garbinti, B, J Goupille-Lebret and T Piketty (2018), “Income Inequality Dynamics in France 1900-2014: Evidence from Distributional National Accounts (DINA)”, Journal of Public Economics 162: 63-77.

Katz, L and K Murphy (1992), “Changes in Relative Wages, 1963-1987: Supply and Demand Factors”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(1): 35-78.

Piketty, T, E Saez and S Stantcheva (2014), "Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6(1): 230-271.

Piketty, T, E Saez and G Zucman (2018), “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(2): 553-609.

Endnotes

1 We follow Garbinti et al. (2018) to obtain pre-tax inequality series for France, using the same methodology and updating estimates to 2018.

2 Note that this comparison is made possible by the fact that both series are based on the very same methodology and are anchored to national accounts. See Alvaredo et al. (2020) for a complete presentation of the general methodology to construct pre-tax and post-tax distributional national accounts.

3 We have also computed other inequality indexes – such as Gini and Theil indexes and Palma and P75/P25 ratios – to measure the change in inequalities over time and find similar results.