Whether the current pick-up in inflation in many advanced countries will be short-lived or forewarns a return to the high inflation of the 1970s is one of the major economic debates of the day. For the US, Ball et al. (2021) argue that “if the fiscal expansion is temporary and monetary policy remains clearly communicated and decisive, there is little risk of a 1960s-type inflationary spiral” – a view shared by Gagnon (2021), Krugman (2021), and Bernstein and Tadeschi (2021). Central bankers remain confident that they have successfully anchored inflation expectations to such an extent that recent increases will not lead to an inflationary spiral (Powell 2021). Recent BIS work (Budianto et al. 2021) argues that the pickup in inflation in many countries is due largely to temporary factors, while medium-term inflation is “moving towards central bank targets”.

Other observers are less sanguine. For example, Blanchard (2021) and Summers (2021) argue that fiscal stimuli of the magnitude contemplated by the US administration carry substantial risks of raising inflationary expectations and triggering sustained inflation.

Inflation and wage gaps

Part of the uncertainty over the future of inflation arises because of instability in the Phillips curve – a key component of the intellectual scaffolding that economists use to analyse and forecast the course of inflation. Recent research (Voinea 2021) shows a stable relationship between inflation and the cumulative wage gap (the cumulative difference between current real wages and the last peak real wage prior to an episode of income loss). The ‘defensive expectations’ theory behind the relationship asserts that after an income loss, households will not spend more until they fully recover what they have lost.

The theory is consistent with historical views. Duesenberry (1952) posited that consumption is dependent not just on the absolute level of income but on “current income relative to past income”; Akerlof (1982) argued that individuals’ perceptions of a fair wage were influenced by their wages in past periods; and Deaton (1991) and Carroll (1997) see savings behaviour as driven in part by a desire to maintain a target wealth-to-income ratio.

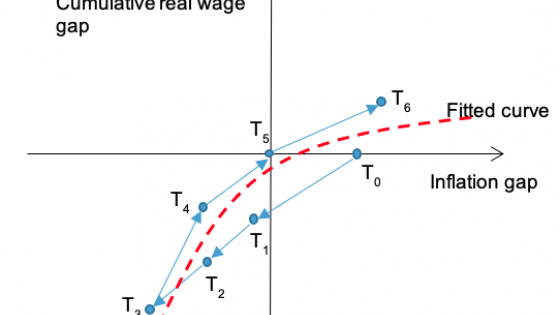

The implication of this more realistic view of household consumption and savings for aggregate demand (and thus for inflation) is that inflation will not rise above its long-run target level until the cumulative wage gap closes. A stylistic representation of the process is shown in Figure 1. Inflation falls below its long-run target level when the economy suffers an episode of income loss (e.g. during a recession or financial crisis) and remains there even as the economy starts to recover as long as real wages remain below their previous peak. It is only after the cumulative wage gap is closed that inflation rises above the long-run level.

Figure 1 The cumulative wage gap Phillips curve

Source: Voinea (2021)

Empirical support for the theory (the counterpart to the fitted curve shown in Figure 1) comes from data for 35 OECD countries over the last three decades. Using panel estimation, with country fixed effects included in the regressions, there is a stable relationship between the inflation gap (the difference between inflation and either the central bank target or a long-run average) and the cumulative wage gap. This is shown in first two rows of Table 1, which reports estimates of the Phillips Curve slope using two alternate wage indicators.

Table 1 Phillips curve estimates for 35 OECD countries, 1990-2018

Source: Voinea (2021).

Note: The dependent variable is inflation relative to central bank target or past long-run average.

The remainder of the table reports estimates of the slope distinguishing between periods when the cumulative wage gap is negative and when it is positive. The conjecture based on the theory developed above would be that the cumulative wage gap plays a more important role when it takes negative values – because people try to make compensatory savings to regain previous wage levels, therefore deterring aggregate demand. There is support for this conjecture when real compensation is used as the wage indicator (the slope is twice as large for negative gaps as for positive) and less so when only the wage component of compensation is used.

Inflation and COVID-19

What does this evidence imply about the course of inflation in OECD economies in coming years? Taking the US as an example, prior to the pandemic, peak wage and disposable income levels were recorded in February 2020. Since then, until April 2021, the cumulative wage gap has been negative, which would suggest that inflationary pressures should have remained dampened. But the substantial (and appropriate) fiscal support to households provided by governments means that there have been substantial one-off increases in disposable income. For instance, one in seven adults in the US received unemployment benefits in 2020 compared to only one in fifty in 2019. The scale and duration of support was also more generous than during many past recessions. US households also received other cash transfers and indirect support through steps such as suspension of eviction for non-payment of rent.

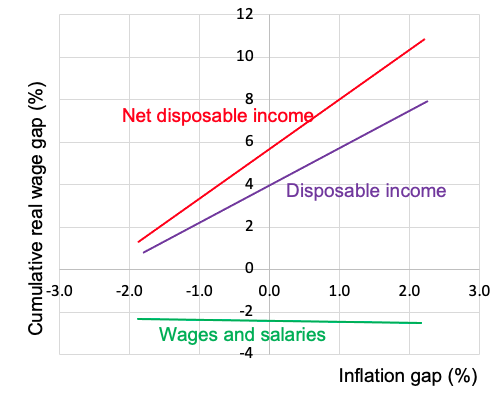

Though it is difficult to estimate relationships precisely over the short period since the start of the pandemic, our estimates with monthly data suggest that this sharp one-off increase in disposable income is feeding an increase in inflation, even though wages remain clearly below their previous peak. The relationship is depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2 Relationship between inflation, income and wages in the US, February 2020 to April 2021

Note: Annualized, seasonally adjusted data. Net disposable income represents disposable income net of income on assets.

Source: Authors, based on FRED database

In many other OECD countries, which have provided less fiscal support than the US government (in part because they have mechanisms in place to better shield workers from sharp wage cuts during recessions), inflation pressures seem to be more contained.

As income support provided during the pandemic starts to be scaled back, and supply bottlenecks are overcome, we would expect that the strong relationship between inflation and cumulative wage gaps would once again reassert itself. In most OECD countries, the cumulative wage gap is negative and far from closing, suggesting that current inflationary pressures would recede.

The rate at which cumulative wage gaps close in turn depends on a number of factors, notably on workers’ bargaining power, which has eroded over time in many OECD economies (Lombardi et al. 2020). In the early months of the pandemic, it seemed that appreciation of the heroic role played by essential workers (such as health care workers and grocery store cashiers) would lead to a change in norms and consequent improvement in bargaining power and wages. But recent evidence suggests that, like previous major epidemics, Covid-19 will have a disproportionately adverse impact on wage prospects of those in low-income deciles and low educational attainment (Furceri et al. 2020). As Budianto et al. (2021) argue, without a “material pickup” in wage costs, there is unlikely to be a more persistent increase in inflation.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are the sole responsibility of the authors and should not be attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its management. Horatiu Lovin provided excellent research assistance.

References

Akerlof, G A (1982), “Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 97(4): 543-569.

Ball, L, G Gopinath, D Leigh, P Mishra and A Spilimbergo (2021), “US inflation: Set for Take-Off?”, VoxEU, 07 May.

Bernstein, J and E Tedeschi (2021), “Pandemic Prices: Assessing Inflation in the Months and Years Ahead”, The White House blog, 12 April.

Blanchard, O (2021), “In defense of concerns over the $1.9 trillion relief plan”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Realtime Economic Issues Watch, 18 February.

Budianto, F, G Lombardo, B Mojon and D Rees (2021), “Global reflation?”, BIS Bulletin 43.

Carroll, C D (1997), “Buffer-Stock Saving and the Life Cycle/Permanent Income Hypothesis”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(1): 1-55.

Deaton, A (1991), “Saving and Liquidity Constraints”, Econometrica 59(5): 1221-1248.

Duesenberry, J S (1952), Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior, Harvard Economic Study 87, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

Furceri, D, P Loungani, J D Ostry and P Pizzuto (2020), “COVID-19 will raise inequality if past pandemics are a guide”, VoxEU, 08 May.

Gagnon, J (2021), “Inflation fears and the Biden stimulus: Look to the Korean War, not Vietnam”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Realtime Economic Issues Watch, 25 February.

Lombardi, M, M Riggi and E Viviano (2020), “Understanding the Phillips Curve through the lens of workers’ bargaining power and business cycle fluctuations”, VoxEU, 22 December.

Krugman, P (2021), “What Inflation Risks and My Intermittent Fasting Have in Common”, Opinion, The New York Times, 23 July.

Powell, J (2021), “Transcript of Chair Powell’s Press Conference”, Federal Reserve, 28 April.

Summers, L H (2021), “The Biden stimulus is admirably ambitious. But it brings some big risks, too”, Opinion, The Washington Post, 04 February.

Voinea, L (2021), Defensive Expectations. Reinventing the Phillips Curve as a Policy Mix, London: Palgrave Macmillan.