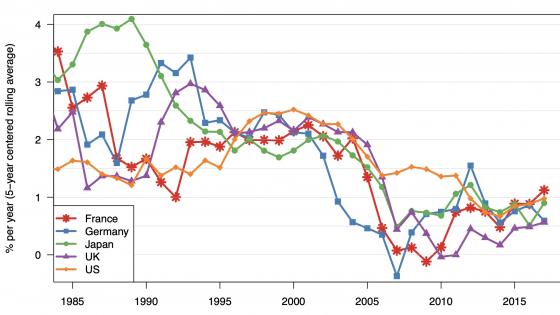

Real pay of typical workers has grown much more slowly than productivity over recent decades in several developed economies. This growing gap has been well-documented in the US (Bivens and Mishel 2015, 2021), Canada (Williams 2021), the UK (Teichgräber and Van Reenen 2021), and elsewhere. This phenomenon – often referred to as a ‘divergence’ or ‘decoupling’ of the pay of typical workers from productivity growth – is all the more striking because it has not always been this way. Bivens and Mishel (2015), for example, document that in the US, labour productivity and the average pay of typical workers grew at the same rate from the late 1940s until the mid 1970s, when the decoupling began.

The fact that productivity has grown so much faster than the pay of typical workers raises the question: Does productivity growth actually benefit typical workers by raising their pay? Or do the fruits of any incremental increase in productivity growth flow only to those higher in the income distribution?

Understanding the strength of this productivity-pay relationship is of considerable policy significance. Given the recent productivity slowdown (Goldin et al. 2021), economic policymakers have focused on measures to accelerate productivity growth such as promoting investment, technological progress, or better functioning markets. If productivity-pay divergence has been accompanied by ‘delinkage’ – whereby year-on-year increases in the rate of productivity growth are not associated with pay growth for typical workers – then success or failure of these efforts to boost productivity will have little impact on middle-class wellbeing. In this case, only measures targeting the income distribution will be effective at raising middle-class incomes. In contrast, if despite divergence between productivity and middle-class pay there is still linkage between the two, then an incremental increase in productivity growth should act to increase the pay of typical workers – even if other variables (like the declining bargaining power of workers, or the increase in globalisation) are at the same time acting in the opposite direction.

In our recent paper (Greenspon et al. 2021), we ask the question: To what extent does an incremental increase in labour productivity growth translate into increased compensation growth?. We look at both the US and Canada, over the period 1961–2019 (updating the analysis for the US in Stansbury and Summers 2018). We regress labour productivity growth on real compensation growth – measured at the average, at the median, and for measures of the compensation of ‘typical’ workers in both the US and Canada – with the possible results falling on a spectrum from complete delinkage (a one percentage point higher productivity growth rate is not associated with any change in the compensation growth rate) to complete linkage (a one percentage point higher productivity growth rate is associated with a one percentage point higher compensation growth rate).1 To focus on the impact of productivity growth over horizons longer than the business cycle, we use three-year moving averages and control for unemployment.

We find strong evidence of linkage in the US. In years with a one percentage point higher productivity growth rate, there tends to be close to one percentage point faster growth in compensation – whether for average compensation, median compensation, or for typical workers (which we proxy using average compensation for production/nonsupervisory workers).

For Canada, the evidence on the linkage between productivity and pay is more mixed. For average workers, we find moderate linkage – over 1961 to 2019, a one percentage point higher productivity growth rate is associated with about half a percentage point faster rate of compensation growth. Over 1961–2019 we also find evidence of very strong linkage for typical workers, whose compensation we proxy using a newly constructed measure of the compensation of hourly-paid workers in five industries.2 However, for more recent periods, estimates for both average and typical compensation are too noisy to rule out strong delinkage (no translation of productivity increases to pay growth). We find no evidence of linkage for median compensation, but caution that our measure of median hourly compensation likely incorporates significant noise, which may substantially attenuate results estimated from year-to-year changes.

Figure 1 Estimates for degree of linkage from compensation-productivity regressions

While the picture is clearer for the US than for Canada, these results overall suggest that in both countries, marginal increases in productivity growth raise compensation on average, including for typical workers (holding all else equal). This is despite the divergence between productivity growth and compensation growth in the US and Canada over the last five decades.

How can there be linkage between productivity and pay even as they diverge? If the productivity growth rate is consistently faster than the growth rate of median compensation – by a fixed amount, say a wedge of 1 percentage point – this leads to the gap between productivity and median pay expanding over time (i.e. divergence). But, conditional on this 1 percentage point wedge between the two growth rates existing, it may nonetheless be the case that in years when productivity growth was faster than average, median pay growth was faster than average too (and vice versa). This would tend to suggest that incremental increases in productivity growth rate feed through into higher pay growth for typical workers. Yet other, long-term factors have been pulling down pay even as productivity has been acting to raise it – so that on net, pay has grown much less than productivity.

This is illustrated by a simple metaphor. Consider a bucket containing some level of water (pay) being filled from a hose connected to a tap (productivity growth). The observed divergence between productivity and pay is analogous to the tap running, but the water level not increasing. This could have occurred because the hose does not actually connect the tap to the bucket, in which case increasing the water flow will not make any difference to the water level (delinkage – increasing the rate of productivity growth won’t affect pay). Or, the problem may not be with the hose but may be that there is a hole in the bucket. In this case, increased water flow from the tap cannot fix the hole in the bucket, but it nonetheless results in a higher water level in the bucket than would have occurred with a slower flow of water (linkage – faster productivity growth acts to increase pay relative to a world with slower productivity growth, even if other factors are acting to reduce pay at the same time).

Why does there appear to be a weaker linkage between productivity and pay in Canada than in the US? Canada is a smaller, more internationally open economy than the US. One possible explanation is therefore that the smaller and more open the economy, the greater the degree to which productivity and real compensation may be determined abroad rather than domestically – and the less, therefore, one might expect researchers to be able to detect a process where domestic productivity increases translate into increases in real compensation. We present some evidence consistent with this hypothesis: there is weaker linkage between average compensation and productivity in regions of the US – which are similar in GDP and population to Canada, and could be considered small open economies – than for the US as a whole. The coefficients estimated for US regions are similar in magnitude to those estimated for Canada.

Another interesting point of comparison is that despite much slower labour productivity growth in Canada than in the US, the growth in real median compensation has been about the same in both countries since 1976 due to relatively larger increases in labour income inequality in the US.

While our focus has been on the relationship between productivity growth and wages, both are of course determined by deeper economic forces like the extent of capital accumulation and the nature of technical innovation. It would be valuable in future work to explore possibility that changes in productivity growth coming from different sources have different impacts on wage growth.

Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that productivity growth still matters for middle-class income growth. Measures to boost productivity growth are important for raising pay for the average and typical worker – and conversely, a continued productivity slowdown will reduce the likelihood of increased real compensation. This does not mean policymakers should ignore measures to improve redistribution, since productivity growth alone is not enough to substantially raise middle-class incomes, particularly in the face of other downward pressures on pay. However, it does mean that policy should not focus only on these issues and ignore productivity growth. Policymakers should utilise all measures in their toolkits – both those that boost productivity growth and promote inclusion – in order to have the greatest impact on middle-class living standards.

References

Bivens, J and L Mishel (2015), “Understanding the Historic Divergence between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay: Why It Matters and Why It’s Real,” Economic Policy Institute

Bivens, J and L Mishel (2021), “The Productivity-Median Compensation Gap in the United States: The Contribution of Increased Wage Inequality and the Role of Policy Choices,” International Productivity Monitor 41.

Greenspon, J, A Stansbury and L H Summers (2021), “Productivity and Pay in the United States and Canada,” International Productivity Monitor 41.

Goldin, I, P Koutroumpis, F Lafond and J Winkler (2021), “Re-evaluating the sources of the recent productivity slowdown”, VoxEU.org, 31 May.

Stansbury, A and L Summers (2018), “On the link between US pay and productivity” VoxEU.org, 20 February.

Teichgräber A and J Van Reenen (2021), “Have productivity and pay decoupled in the UK?,” International Productivity Monitor 41.

Williams, D (2021), "Pay and Productivity in Canada: Growing Together, Only Slower than Ever," International Productivity Monitor 40.

Endnotes

1 Specifically, we regress the change in log of annual labor productivity (measured as net output per hour) on the change in log of hourly real labor compensation, controlling for the level and lagged level of the unemployment rate. In our baseline specifications, all variables are three-year moving averages, standard errors are Newey-West heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent, and compensation is deflated by the PCE in the US and the HCE in Canada.

2 These are five industries that we believe are most likely to provide employment opportunities during times of growth and for which historical time series data is available from 1961 onward: manufacturing, mining, construction, laundries, and hotels and restaurants. These made up 34 per cent of total employment in 1961 and 24% by 2011.