The COVID-19 outbreak is a health shock rather than a standard slowdown in economic activity. It is materialising as an unavoidable temporary economic paralysis, and its consequences will likely amount to a severe contraction of the global economy and a global financial crisis. The collective attempts to avoid the spread of the virus are needed desperately, but such containment action will also likely lead to an almost full suspension of economic activity in many parts of the economy.

The recourse to standard expansionary fiscal and monetary policies may not be effective right now. Textbook expansionary policies try to stimulate demand, but people who simply stay at home are not currently responsive to such stimulus, which may in fact reduce these policies’ firepower when it is needed later on. ‘War time’ economic thinking should dictate that the virus is the external enemy and needs to be defeated at all costs to recover an economy that functions in a regular way. It calls for a host of targeted policies, as suggested by the IMF Chief Economist Gita Gopinath early on (Gopinath 2020).

Part of this thinking is about figuring out the essence of the shock and its economic transmission in the short run. For macroeconomists, the crisis appears to currently materialise both as a demand shock and a supply disruption. It is also important to pin down whether the shock will lead to a liquidity or a solvency problem for the real sector.

A pure liquidity problem arises when one learns that the return coming today will instead come tomorrow; all that is needed is to manage liquidity accordingly, for example through a loan. A pure solvency problem is associated with a lack of long-term viability. Solvency issues do likely not apply to the majority of the businesses affected by the current paralysis. Once the epidemic is over and the economy recovers, most businesses should be as profitable as before. SMEs, however, may now go bankrupt. The effects from such default are well-known: lay-offs, non-performing loans, weaker banks, weaker demand, sluggish investment, and a sluggish recovery.

Thus, the losses of the economic paralysis should be shared. Preserving the medium-and long-term continuity of businesses is important for society.

How to address the liquidity squeeze faced by small businesses?

Several governments have already taken decisive action to address companies’ looming liquidity shortfalls. As a notable example, the German government was quick to legislate a package of economic measures, which includes tax deferrals, as well as unlimited access to loans via Germany’s state-owned development bank KfW.1

While these policies are extremely welcome and legislation was rapid, there might still be an issue on the magnitude and timely implementation. First, tax deferrals will allow business to delay payment of outstanding tax liabilities. There is large variation across firms in how the magnitude of these liabilities compares to the dramatic reduction in revenues from the contraction in economic activity.

Second, it is unclear whether the administrative process involved in asking for emergency loans can be executed timely enough. For example, will the owner of a small café or a laundry store be able get access to such an emergency loan to service outstanding payments while demand has already virtually collapsed to zero?

Alternative: An immediate negative lump sum tax for SMEs

Many firms need liquidity urgently – it is a matter weeks or even days. What if the government provides small businesses with an immediate negative lump-sum tax?

The magnitude of this government transfer could be determined as a share of the firms’ revenues or costs in 2018 (or a share of an average over past years). How high the share should be (it could in principle be 100% or even above) would depend on how much the government is willing to spend on the program. Further below we provide calculations based on the firms’ payroll.

The negative tax could come with some conditionality, for example requiring firms to hold on to their employees. It could be targeted to a subset of firms or industries, ideally to firms below a certain employment threshold, as for these firms the implementability constraint of existing measures, pointed out above, likely binds. Furthermore, it could either come as full-on transfer (pretty much making it ‘helicopter money’) or it could be partly reversed in later tax years, when the economy has recovered.

A negative lump sum tax can be implemented fast and translates into cash flow for businesses

Our proposal of a negative tax has the benefit that practical implementation may be swift. For small businesses the problem is a lack of cash and time is already running out. Even if there is the political will to help these businesses, it is logistically tricky to actually send money to firms. A negative lump-sum tax would allow a cash transfer of a magnitude that could exceed that of a deferral of existing tax liabilities. Importantly, immediate means that the government literally directly wires the money to the business’ bank account via the existing tax system infrastructure, right now! It could be done without requiring firms to do any paperwork whatsoever.

In the case of the US, this may be implemented directly via the Internal Revue Service (IRS). Upon successful legislation, the IRS, which should have the required information and infrastructure, could transfer money within days, the way it would do with a standard tax refund. When the threat of bankruptcy is so immediate, it comes down to practical details such as having a database with the firms’ identities and bank account numbers, which can be further linked to U.S. Census database.

We are aware that this is a rather blunt proposal, however we believe that out-of-the box thinking is needed now. We also acknowledge that there are some parameters to be figured out, such as the magnitude and the universe of firms to be targeted. But the basic idea has the crucial benefit that it would directly and immediately address the disruptive liquidity needs of small businesses, where most employment occurs, and where we therefore think policy intervention currently has most kick.

How much money is needed?

We want to substantiate our proposal by providing some quantitative analysis for the US. The idea is to answer the question of how much money would get us how far in supporting US SMEs? To investigate this question, we resort to publicly available data from the US Census Bureau.

In principle, the negative tax could be calculated either based firms’ revenues or based on their costs. Since the payroll is typically the largest cost item for businesses, and job losses started piling up, we focus on the payroll. Note that the UK, for example, has now decided to cover 80% of wages for employees that cannot work because of the outbreak of the virus.2

The numbers we provide below might be useful even beyond our specific proposal as they can be used to put other policies targeted at US businesses into a quantitative context. Table 1 presents statistics on employment and the size of the payroll across the US firm size distribution for the year 2017.

Table 1 Employment and size of payroll across US firms

Source: 2017 SUSB Annual Data Tables, United States Census Bureau.

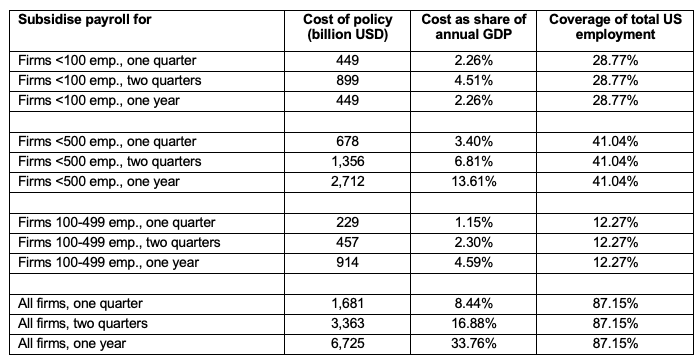

Table 1 shows that a large bulk of US employment is accounted for by relatively small firms. Based on the information in Table 1, we provide calculations for different policy scenarios. In each scenario, we postulate that a certain group of firms (as defined by their size in terms of number of employees) receives direct cash payments to cover their payroll for a specific time period: one quarter, two quarters or a year. How costly would these policies be? Our estimates are given in Table 2. To put the dollar values into context, we measure the cost of potential support policies as a share of US GDP and further include the number of employees covered by a given policy as a share of total US employment.

Table 2 Estimated costs and coverage of different policy scenarios

Notes: Annual GDP and total US nonfarm payroll employment used to compute columns 3 and 4 are taken from FRED for the year 2017. GDP is $19.9 trillion and total employment is 147.6 million. This includes more employees than our numbers in Table 1, which only covers the non-farm, non-government sector.

Can the US afford an intervention?

We believe that Table 2 provides a useful guideline to contextualise the magnitude of potential support payments to US SMEs. Suppose Congress is willing to cover the entire payroll of all firms with fewer than 500 employees for three months. This policy would cover the wage bill of 61 million US workers and would cost around 3% of US annual GDP. Relative to the losses that are looming from businesses shutting down and workers losing their job, we do not consider the numbers in Table 2 too large for policymakers to shy away from aggressive policy. The policy can also be made conditional on firms keeping workers on their payroll, where firms which did not comply have to return the excess payments to the government during next year’s filing.

We further want to stress that our calculations above abstract from any potential general equilibrium effects. In particular, any intervention of the sort we suggest will likely have some multiplier effects. A given firm’s costs are in principle likely to include another firm’s revenue. If a given firm can cover its cost instead of delaying payment or defaulting, this will likely help other firms. Furthermore, making sure that firms will be able to cover their wage bill will put money in households’ pockets and alleviate additional negative effects of the contraction through the labour market.

Policy is hopefully moving in the right direction

US legislators have been discussing various economic measures, including the direct provision of cash to the economy. Our proposed policy of a negative lump sum tax, implemented through the IRS, can achieve exactly this in a quick manner. As we write, additional advice by macroeconomists, given with impressive dedication and at an unprecedented speed through social media, points in a similar direction, for instance by calling for a direct “liquidity life line” to European firms via the EIB.3 It is clear that economists hope to see an aggressive response by policy makers which takes their advice seriously.

References

Baldwin, R (2020), “The supply side matters: Guns versus butter, COVID-style”, VoxEU.org, 22 March.

Drechsel, T and S Kalemli-Ozcan (2020), “Are Standard Macro Policies Enough to Deal with the Economic Fallout from a Global Pandemic?” econfip policy brief 25, March.

Fornaro, L and M Wolf (2020), "Coronavirus and macroeconomic policy", VoxEU.org, 10 March.

Gali, J (2020), "Helicopter money: The time is now", VoxEU.org, 17 March.

Gopinath, G (2020), "Limiting the economic fallout of the coronavirus with large targeted policies", VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Gourinchas, P-O (2020) "Flattening the pandemic and recession curves", in R Baldwin and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, A VoxEU.org eBook.

Endnotes

1 See https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Pressemitteilungen/Finanzpolitik/2020/03/2020-03-13-download-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

2 See https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/20/government-pay-wages-jobs-coronavirus-rishi-sunak?CMP=share_btn_tw

3 See https://voxeu.org/debates/commentaries/throwing-covid-19-liquidity-life-line