Germany introduced a minimum wage in January 2015, setting it at a uniform national level of €8.50. The minimum wage cut deep into the wage distribution, with 15% of workers having earned an hourly wage below €8.50 six months before the minimum wage came into effect. The reform was triggered by falling wages at the bottom of the wage distribution (Dustmann et al. 2009, Marin 2010) and the dwindling importance of trade unions (Dustmann et al. 2014). In the period leading up to its introduction, the minimum wage was viewed critically by many economists and segments of the media (Sachverständigenrat 2013, Der Spiegel 2013, FAZ 2013, Die Welt 2013), with two early studies predicting that it would cause up to 900,000 job losses (Knabe et al. 2014, Müller and Steiner 2013).

Our analysis (Dustmann et al. 2021) shows that the minimum wage significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects. The lack of employment responses, however, masks some important structural shifts in the labour market. Specifically, we show that the minimum wage led to a reallocation of workers from smaller to larger establishments, from lower-paying to higher-paying establishments, and from less to more productive establishments, thereby helping to improve the quality of establishments operating in the economy.

The effect of the minimum wage on wages and employment

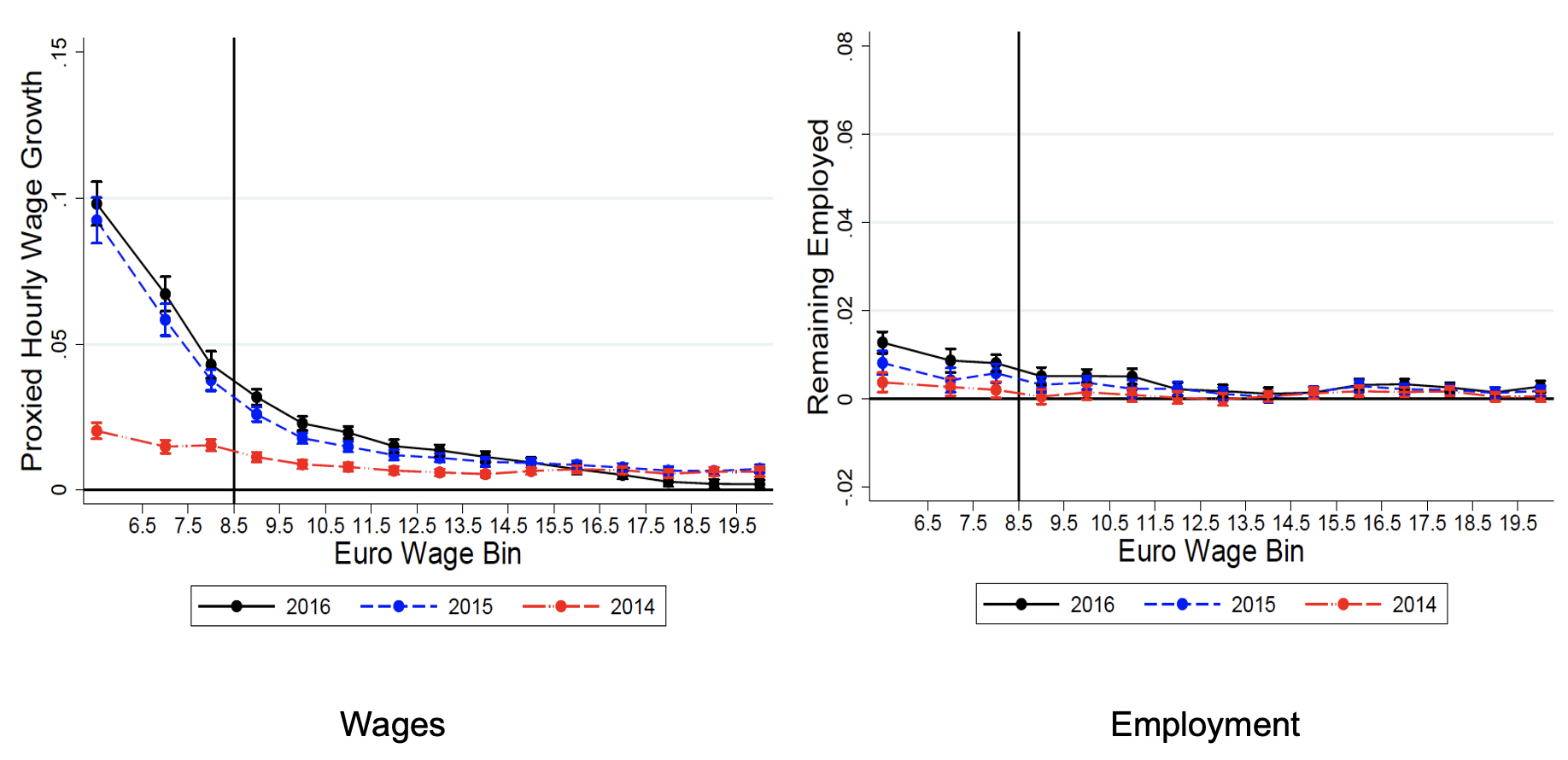

To examine the labour market effects of Germany’s first-time introduction of the minimum wage, we follow individuals over time and contrast individual wage growth and employment changes in periods before the introduction of the minimum wage to those after. The analysis finds that the minimum wage significantly increased wages of low-wage workers. This is illustrated in the left panel of Figure 1, which plots the two-year excess wage growth by initial wage bin (horizontal axis) in the periods 2012 versus 2014 to 2014 versus 2016 against the 2011 versus 2013 pre-policy period, controlling for individual characteristics. The figure clearly highlights that hourly wage growth in the post-policy periods considerably surpasses hourly wage growth over the 2011 to 2013 period for wage bins below the hourly minimum wage of €8.50. Moreover, wage growth also exceeds pre-policy (2011 versus 2013) hourly wage growth for wage bins slightly above the minimum wage, in line with spillover effects of the minimum wage to higher wage bins. In contrast, wage growth for wage bins higher than €12.50 has not been affected by the introduction of the minimum wage.

The right panel of Figure 1 illustrates that there is no indication that the introduction of the minimum wage lowered employment prospects of low-wage workers. Workers directly exposed to the minimum wage (earning less than €8.50 per hour at baseline) are even slightly more likely to remain employed after (i.e. in 2015 and 2016) than before (i.e. in 2013) the introduction of the minimum wage. The small positive employment effects are consistent with the idea that wage increases induced by the minimum wage has made employment a more attractive option for low-wage workers.

In summary, this analysis follows individuals’ wages and employment status over time, and shows that the minimum wage raised wages for minimum-wage workers without lowering their employment prospects. In consequence, the minimum wage policy reduced wage inequality, as intended.

Figure 1 Wage and employment effects of the minimum wage: Individual approach

Notes: The left panel plots two-year excess wage growth by initial wage bin in the periods 2012 vs 2014 to 2014 vs 2016 relative to the 2011 vs 2013 pre-policy period. The right panel plots the probability that an employed worker is employed two years later against her initial wage bin for the periods 2012 vs 2014 to 2014 vs 2016 relative to the 2011 vs 2013 pre-policy period. Underlying regressions control for individual characteristics at baseline.

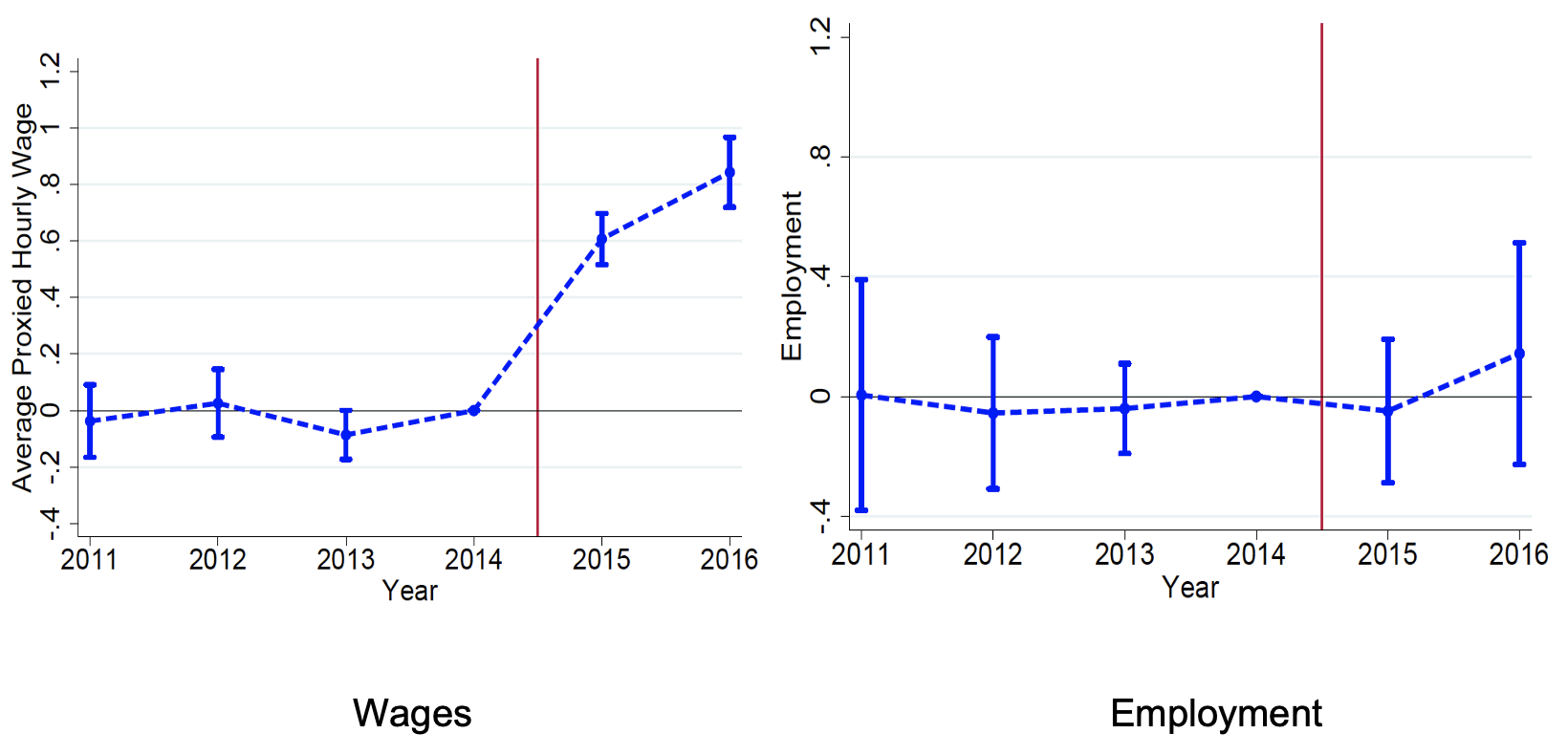

In a next step, we exploit the considerable variation in the exposure to the minimum wage across 401 local areas in Germany, by tracing how (log) local average hourly wages and (log) local employment evolve in districts (‘Kreis’) differentially exposed to the minimum wage, due to differences in pre-policy local wage levels (see Ahlfeld et al. 2018 for a related analysis that uses variation in the minimum-wage bite across regions in Germany). The left panel of Figure 2 shows that relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend, wage growth in highly affected districts strongly picks up relative to wage growth in less affected districts after the introduction of the minimum wage. The right panel of Figure 2 provides a corresponding analysis for the employment effects of the minimum wage and illustrates that the minimum wage had no discernible impact on local employment, in line with our findings from the individual analysis.

Figure 2 Wage and employment effects of the minimum wage: Regional approach

Notes: The panels show how log local average hourly wages (left panel) and log local employment (right panel) evolve in regions differentially exposed to the minimum wage, relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend.

Adjustment of the labour market to the minimum wage introduction

The absence of an employment response, despite a strong wage response, potentially masks structural shifts in the labour market, such as the exit of low-productivity establishments from the market and a shift in employment toward more productive establishments. We present evidence consistent with reallocation at both the individual and regional level. At the individual level, we show that after the introduction of the minimum wage, low-wage workers – but not high-wage workers – are more likely to upgrade to establishments that pay higher wages on average, offer more full-time and more stable employment relationships, pay higher wage premiums to the same type of worker, are larger, and are more productive (as measured by their predicted revenues per worker).

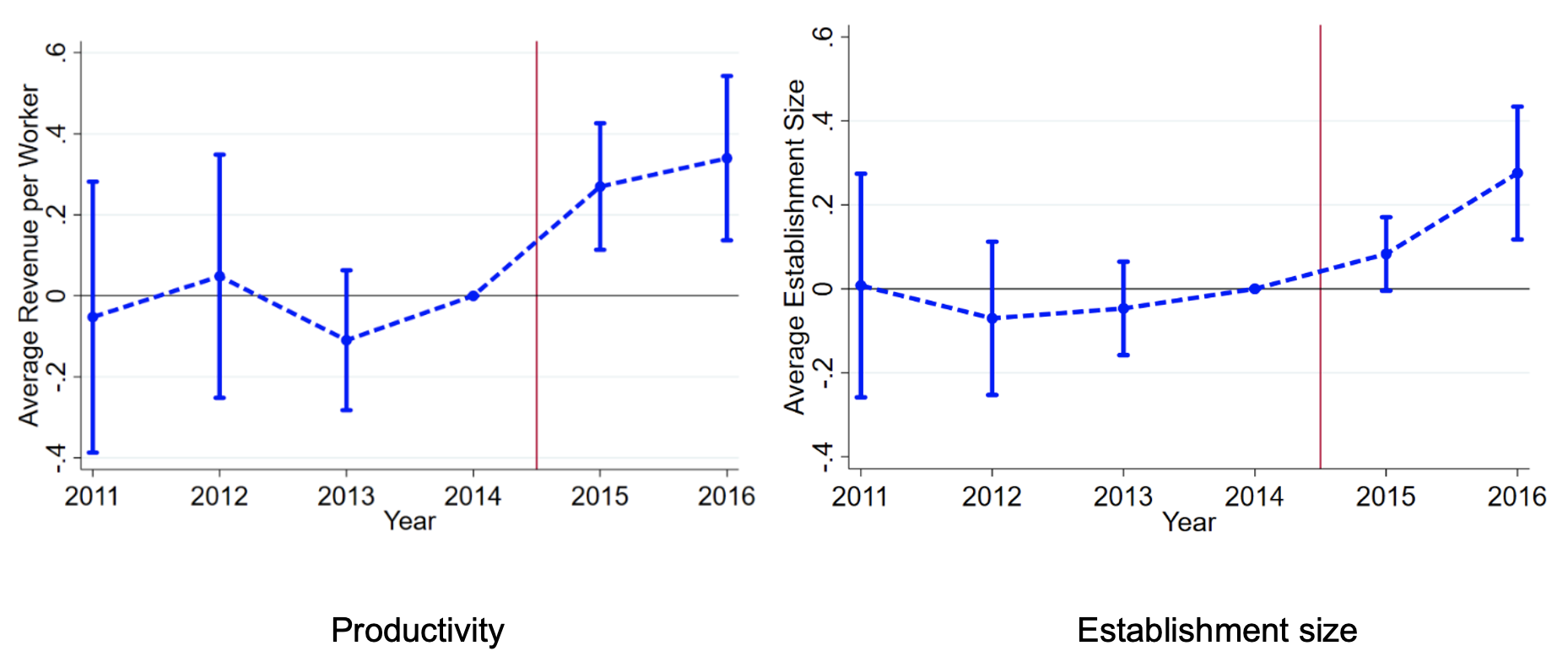

At the regional level, we show that after the introduction of the minimum wage, the quality of establishments improved in local areas highly exposed to the minimum wage, an effect that is driven by the reallocation of workers to more productive establishments within the local area. Figures 3 illustrates this point in terms of productivity (left panel) and average establishment size (right panel), both of which strongly increase in areas heavily exposed to the minimum wage after the introduction of the reform, relative to less exposed areas and 2011–2014 pre-policy trends. In a similar vein, we show that the minimum wage induced some small businesses with fewer than three employees to exit the market, signalling a shift toward establishments that pay higher wage premiums to the same type of worker in more- relative to less-exposed areas.

Figure 3 Reallocation effects of the minimum wage: Regional approach

Notes: The panels show how (predicted) log mean revenue per worker (left panel) and log mean establishment size (right panel) evolve in regions differentially exposed to the minimum wage, relative to the 2011–2014 pre-policy trend.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the concerns among many economists that the introduction of the minimum wage in Germany in 2015 would cause substantial job losses were unfounded. Rather, we show that the introduction of the minimum wage boosted wages of low-wage workers, did not lower employment, and induced a reallocation toward more productive establishments. As such, the minimum wage has helped to reduce wage inequality, across workers and local areas. These results do not imply that no establishments or workers lost out as a result of the introduction of the minimum wage. For example, the minimum wage caused some small businesses to exit the market. Moreover, the reallocation of low-wage workers to higher paying establishments came at the expense of increased commuting time, which might have left some workers worse off despite earning a higher wage. Nevertheless, even though there might be some losers from the minimum wage policy, we conclude that the overall welfare of low-wage workers likely increased in response to the introduction of the minimum wage.

References

Ahlfeldt, G, D Roth and T Seidel (2018), “Spatial implications of minimum wages”, VoxEU.org, 04 September.

Der Spiegel (2013), “Ökonomen warnen vor zu hohem Mindestlohn”, 20 October.

Die Welt (2014), “Mindestlohn bedroht Hunderttausende Jobs im Osten”, 03 December.

Dustmann, C, J Ludsteck and U Schönberg (2009), “Revisiting the German Wage Structure”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124: 843–881.

Dustmann, C, B Fitzenberger, U Schönberg and A Spitz-Oener (2014), “From sick man of Europe to economic superstar: Germany’s resurgence and the lessons for Europe”, VoxEU.org., 13 February.

Dustmann, C, A Lindner, U Schönberg, M Umkehrer and P Vom Berge (2021), “Reallocation effects of the minimum wage”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

FAZ (2013), “Aufruf von Wirtschaftsprofessoren: Ökonomen fürchten Mindestlohn ohne Sachverstand”, 19 December.

Knabe, A, R Schöb and M Thum (2014), “Der flächendeckende Mindestlohn”, Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik 15: 133–157.

Marin, D (2010), “Germany’s super competitiveness: A helping hand from Eastern Europe”, VoxEU.org, 20 June.

Müller, K U and V Steiner (2013), “Distributional Effects of a Minimum Wage in a Welfare State: The Case of Germany”, SOEP papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 617.

Sachverständigenrat (2013), “Jahresgutachten 2013/2014. Gegen eine rückwärtsgewandte Wirtschaftspolitik”, Wiesbaden.