When leaders met for the G20 Summit in Saint Petersburg last weekend, they welcomed the incipient recovery in the Eurozone. However, they also recognised that "despite our actions the [global] recovery is too weak" and fraught with risks. This is particularly relevant for the Eurozone, firstly because GDP growth in the area itself is still very weak and uneven, and secondly because, in the current external macroeconomic environment, the Eurozone economy can expect to get only a limited boost from external demand (in spite of its growing current account surplus). Addressing the weakness of domestic growth, exploiting the cyclical developments to make growth more sustained and sustainable, and therefore removing impediments to private investment, is vital.

A subdued and fragile recovery

Over the past few months, economic news from the Eurozone has been encouraging. After six quarters of contraction, GDP surprised on the upside in the second quarter, expanding by 0.3% compared to the previous quarter. The latest GDP release also shows further progress in intra-Eurozone rebalancing, with a strong export performance in some vulnerable member states and welcome signs of strengthening domestic demand in the core. Overall, the recession has now given way to a modest recovery, and key indicators are signalling a continuation along this path in the second half of this year and a recovery gaining traction next year.

However, this is no time for complacency. Short to medium term growth prospects remain subdued and the recovery is fragile, surrounded by downside risks (see Commission's Spring 2013 forecast, OECD Economic Outlook, May 2013). Lacklustre economic growth does not come as a surprise as it is in line with experiences from recoveries following systemic financial crises (see Reinhart and Rogoff 2009 and 2012). This reflects the needs for balance-sheet repair and sectoral rebalancing, the lack of which hold back demand and weigh on labour markets. Nevertheless, while this consideration applies to all advanced economies which entered the recession with significant financial imbalances, the growth shortfall of the Eurozone compared to the US is striking.

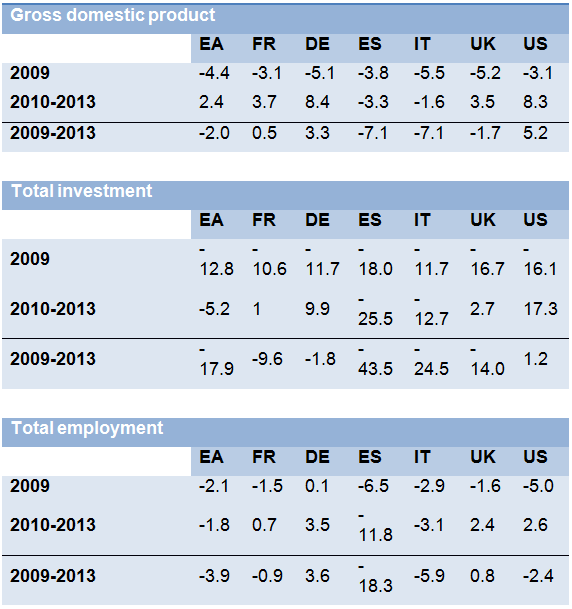

A notable difference with the US is the drawn-out contraction of investment in the Eurozone after the Great Recession. In the US, investment fell sharply in 2008-09, but has registered positive growth in ten out of 14 quarters since the beginning of 2010. In the Eurozone, investment picked up briefly in 2010, but declined for eight straight quarters thereafter (Table 1). The picture is similarly grim for employment, with the notable exception of Germany.

Table 1. GDP, investment and employment (annual % growth)

Source: European Commission, 2013 spring forecast.

This suggests that factors specific to the Eurozone and most of its member states are adding to the usual obstacles to growth in the post-financial-crisis world. Deleveraging and bank balance sheet repair have been markedly slower in the Eurozone than in the US, and this lack of progress is weighing on both credit demand and credit supply, and thereby on investment. For instance, returns on banks' assets have recovered significantly in the US since their trough in 2009 but have remained under pressure in the Eurozone, particularly in vulnerable countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bank returns on assets (in %)

Source: IMF.

Balance-sheet repair in the Eurozone has been hampered by what are now well-known faults in the Eurozone's architecture. In particular, in the absence of a proper banking union, uncoordinated national responses to banks' balance-sheet difficulties have led to a damaging degree of fragmentation of the single financial market that has pushed financing costs to very high levels in some member states (Figure 2), triggered negative bank/sovereign feedback loops, and ultimately threatened the very survival of the single currency. Faults in the architecture of Eurozone have been compounded by deep macroeconomic and structural imbalances in many member states that have slowed the adjustment of the economy, notably in terms of sectoral reallocations. This has been strikingly reflected in the widening gap in productivity growth between the US and the Eurozone since the crisis.

Figure 2. Interest rates on loans to non-financial corporations (maturity up to one year, in %)

Source: ECB, DG ECFIN calculations.

A targeted policy response to make the recovery durable

The incipient recovery reflects the disappearance of tail risks due to the determined action of the Eurozone governments and the ECB. The ensuing increase in confidence is evident in many early indicators. It is vital to build on such positive signs to foster a durable recovery. Key to this is creating the conditions for stronger investment and hence employment creation.

What has to be done to unlock investment in the Eurozone? We can think of three conditions that are necessary for investment to pick up:

1. Reducing policy uncertainty.

2. Repairing the financial system.

3. Creating new investment opportunities.

These conditions, if fulfilled, will be self-reinforcing and will enhance medium-term growth potential.

For these conditions to be fulfilled, action is needed at both the European and the national level, both on the demand side, by boosting investment demand, and on the supply side, by accelerating a much-needed structural change in the economy.

Reducing policy uncertainty

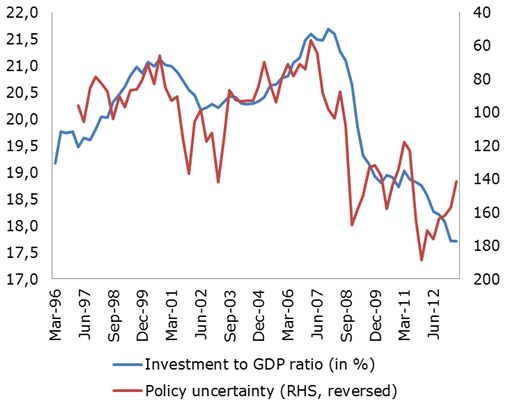

Announcing and implementing such a plan will address the exceptionally high level of economic and policy uncertainty, which is an impediment to investment decisions (condition 1). There is empirical evidence that uncertainty can significantly and negatively weigh on private spending and economic growth by offering agents an incentive to postpone investment, consumption and employment decisions (see QREA, Vol. 12, no. 2) (Figure 3). At the current juncture, high uncertainty is all the more damaging for growth as it magnifies the effect of credit constraints and weak balance sheets, forcing banks to rein in credit further and companies to hold back investment, even if they are not liquidity constrained, to minimise the risks of irreversible decisions.

Figure 3. Policy uncertainty and investment

Source: Eurostat and Baker, Bloom and Davis at www.PolicyUncertainty.com.

Ensuring a fully functional financial system

A critical step towards restoring full functionality of the financial system (condition 2) is the repair of bank balance sheets. This requires both transparency regarding the current health of bank balance sheets and proper recapitalisation where needed. The forthcoming asset quality review and stress tests, ahead of the move to a single supervision authority, will be instrumental in this respect and will have to be carried out earnestly and credibly. Recapitalisation will have to be underpinned by appropriate backstops.

Completion of a fully-fledged banking union is critical to ensure financial stability, reverse the process of financial fragmentation and restore the flow of credit to the corporate sector. The need for a single centralised mechanism for the supervision and restructuring of banks is clear, and a full Banking Union will require not only a Single Supervisory Mechanism but also a Single Resolution Mechanism with a common resolution fund and a common fiscal backstop. A full banking union will support investment not only through its effect on fragmentation and the cost of borrowing, but also by providing a more stable, transparent, and predictable financial environment.

Specific efforts should also be made to restore credit flow to SMEs, which are the main driver of investment and employment in Europe and have been overly hit by financial fragmentation. On-going joint work in that area by the Commission and the EIB, in liaison with the ECB, should be pursued.

Implementing an ambitious structural reform agenda

Measures to fix the financial sector will restore access to credit and are a precondition for investment, but they should be complemented by structural measures to boost investment opportunities and the economy's medium-term growth prospects (condition 3). Without a credible and ambitious structural-reform agenda at the Member State level, the recovery is unlikely to shift up a gear or even to repair the (still to be fully measured) damage that the crisis has caused to potential output. Conversely, failure to restore credit to the economy would limit the potential benefits of structural reforms by preventing firms from taking full advantage of new investment opportunities.

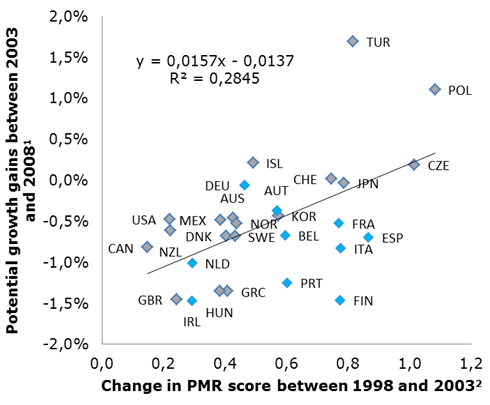

Although some progress has been made in recent years, more can still be done to boost the Eurozone's growth potential (see Buti and Padoan 2012). Reforms in product markets in particular have the potential to unleash new investment opportunities, and evidence shows that they can have a significant positive effect on growth over the medium term (Figure 4). Simulations carried out by the OECD (Johansson et al. 2013) also show that over the medium term an ambitious structural-reform agenda, including both product- and labour-market reforms, would deliver large growth benefits in the Eurozone (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Progress on product-market reforms is associated with better growth performance

Note: euro area countries shown in blue, others in grey.

1 The gain in potential growth is the difference between the average annual rate of growth of per capita potential GDP in 2003-08 relative to the average for 1998-2003. Most countries experienced slower average per capita growth in the second five-year period, so the positive growth effect of product-market reform would generally mean that the growth slowdown would have been greater with less reform.

2 The OECD's Product Market Regulation (PMR) indicator is defined such that a higher number indicates more restrictive policy settings. Here the sign of the change is inverted, so that an increase indicates a move to less restrictive policy settings.

Source: OECD EO93 database, and OECD calculations.

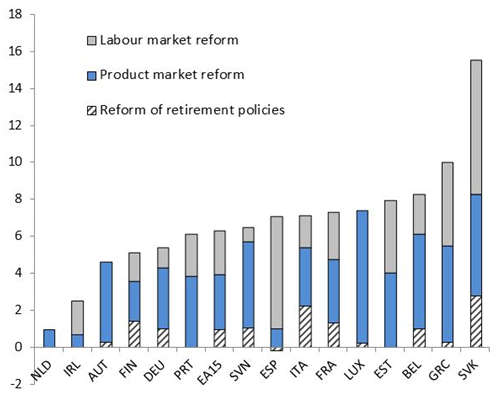

Figure 5. Structural reforms raise long-run output - Difference in the level of GDP in 2025 (%)

Note: The size of each bar shows the effect on GDP of each policy simulated in isolation. The reform of retirement policies assumes that the ratio of working-life to life-expectancy converges towards that of Switzerland. Labour market reforms are assumed to gradually reduce the structural unemployment rate to 5% in all countries where it would otherwise be above this level. Product market reforms move each country's regulations gradually towards best practice.

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook 93 long-term database.

Vulnerable member states have recently pushed through impressive structural reforms. These achievements notwithstanding, further progress is needed to create investment opportunities that will help in shifting resources towards the production of tradable goods and services, raising external competitiveness and boosting productivity, and thus addressing the imbalances that were at the root of the Eurozone crisis. In member states in the core area, reform efforts have generally been less ambitious so far, and product market reforms aimed at improving competition in non-tradable sectors would spur investment and facilitate the development of these sectors. By strengthening the role of domestic demand in the composition of growth, this would strengthen these countries' resilience to external shocks and make the adjustment in the Eurozone more symmetric.

Implementing the measures discussed here rapidly and credibly would boost confidence and reduce uncertainty while paving the way for more robust medium-term growth. Higher confidence, lower uncertainty, and better access to credit would support firms' investment and short-term economic growth, but would also make ambitious structural reforms easier to implement politically and allow economic agents to reap their full benefits. This is why there is no room for complacency. The cost of procrastination or dithering would be high, involving a double penalty on the economy as growth losses due to lack of reforms would be compounded by growth losses due to persistently high uncertainty and subdued confidence.

Procrastination is not inevitable, however, and policy action should be encouraged by the expected growth benefits. Such benefits and the strategy that will make them materialise should be well-communicated so as to enhance consensus. It is essential that the vicious circles that have marred the Eurozone economy in the past are turned into a powerful virtuous circle where growth feeds confidence and confidence further reinforces activity.

References

Buti, M and P C Padoan (2012), "From a vicious to a virtuous circle in the Eurozone - the time is ripe", VoxEU.org, March 27.

Buti, M and A Turrini (2012), "Slow but steady? External adjustment within the Eurozone starts working", VoxEU.org, November 12.

European Commission (DG ECFIN), European Economic Forecast, Spring 2013, May 2013.

European Commission (DG ECFIN), Quarterly Report on the euro area, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2013.

Johansson, Å et al. (2013), “Long-Term Growth Scenarios”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1000, OECD Publishing.

OECD Economic Outlook, May 2013 No. 93, OECD Publishing.

Reinhart, C M and K S Rogoff (2009), This time is different: eight centuries of financial folly, Princeton.

Reinhart, C M and K S Rogoff (2012), “This time is different, again? The US five years after the onset of subprime", VoxEU.org, October 22.