By the middle of 2020, the world had witnessed its highest recorded number of forcibly displaced people worldwide to date at 80 million persons, including 4.2 million asylum-seekers and 26.3 million refugees.1 While that number includes 4 million refugees from older conflicts in Afghanistan and Somalia, 10.1 million of these are from the more recent crises in Syria, Myanmar, and South Sudan.

On 17 December 2018, after a two-year process of consultations, the United Nations General Assembly affirmed the Global Compact on Refugees “to provide a basis for predictable and equitable burden- and responsibility-sharing among all United Nations Member States, together with other relevant stakeholders as appropriate.”

Underpinning the Global Compact on Refugees and the broader debate on burden- and responsibility-sharing is the assumption that “the grant of asylum may place unduly heavy burdens on certain countries” (United Nations 2018), typically countries neighbouring a conflict area. In this perspective, most refugees move to the closest place where they can find safety and countries neighbouring a conflict area end up accommodating the largest numbers of refugees often for very long periods of time. In other words, the number of refugees a country is hosting is merely a function of its geography.

In a recent paper (Devictor et al. 2021), we examine empirically the proposition that the hosting of refugees falls disproportionately on neighbouring countries, which in most cases are in the developing world. To do so, we use data on worldwide bilateral refugee stocks from 1987 to 2017 compiled by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to examine the spatial distribution of refugees and its evolution over time.

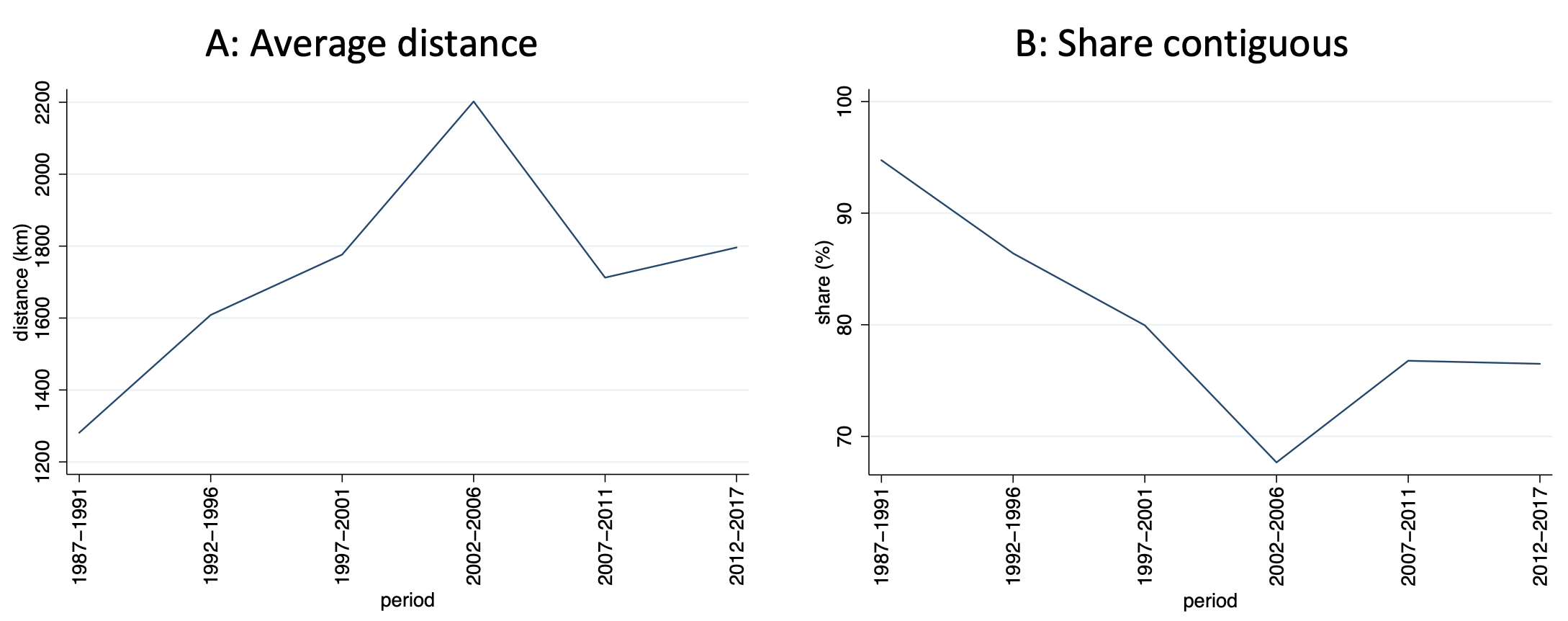

Figure 1 summarises our main findings. While most refugees still remain in a country neighbouring their country of origin, the past decades have seen a trend towards greater geographic diffusion. This suggests that the responsibility-sharing debate taking place among nations needs to be reconsidered in light of the gradually shifting distribution of refugee asylum locations.

Figure 1 Trends in spatial refugee diffusion

Panel A reports the average distance refugees have travelled between their country of origin and their country of destination. There is a pronounced upward trend: the average distance travelled rises from around 1300 kilometres in the late 1980s to 2200 kilometres in the mid-2000s, before settling at around 1800 kilometres in the last decade.

Panel B plots the share of refugees that find themselves in a country that shares a land border with their country of origin. In the late 1980s they accounted for 95% of the total. That share fell to 77% in the period 2012-2017.

Panel C displays the Herfindahl index of refugee shares by country of origin, a statistical indicator of geographical concentration of refugees across host countries. A Herfindahl index of one indicates that all refugees from a given conflict go to one host country, while lower values imply more dispersed distribution across destinations. The analysis shows a substantial decrease in the Herfindahl index since the late 1980s, implying that refugees from a given conflict are now more dispersed across host countries.

Finally, panel D shows that high-income OECD countries host an increasing share of the global refugee population.2 As of 1990, under 5% of refugees resided in a high-income OECD country. This share grew to nearly 25% by the mid-2000s, before falling somewhat to 15%, still triple the 1990 value.

Put together, these results paint a new picture of the global distribution of refugees across the world – and of the corresponding responsibility-sharing. While most refugees remain in a country that is neighbouring theirs, the last few decades have seen a continued trend towards a more globalised and far-reaching refugee network, and a gradual improvement in the sharing of the refugee-hosting responsibilities across countries. While much remains to be done, this is a hopeful development for those who are committed to the objectives of the Global Compact on Refugees.

References

Devictor, X, Q-T Do and A A Levchenko, “The Globalization of Refugee Flows”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15652.

United Nations (2018), “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Part II: Global Compact on Refugees”, UN General Assembly Technical Report.

Endnotes

1 Asylum seekers have crossed a national border and have applied for international protection. When asylum is granted, they become refugees. These figures only include refugees and asylum-seekers under the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Palestine refugees account for another 5.3 million persons and are under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

2 High-income OECD countries in our sample are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States. We thus exclude the newer members of the OECD, such as South Korea, Mexico, or Turkey.