“The American tax code is almost certainly the most complicated in the Western world. The Internal Revenue Service’s taxpayer advocate estimates that in 2008 the direct and indirect costs of complying with that complexity amount to $163 billion each year.”

Teles (2013)

The public choice theory argues that regulation hinders economic growth by creating excessive burdens for economic actors (Niskanen 1971). Regulation can disincentivise firms to upscale, enter a market, innovate, and invest in skill formation (Fonseca et al. 2001, Nicoletti and Scarpetta 2003, Ciccone and Papaioannou 2007, Braunerhjelm and Eklund 2014). However, the introduction of detailed property rights and more broadly, the establishment of a rule of law can safeguard consumers, incentivise investors, and encourage companies to create new technologies (Dam 2007). A certain level of regulation is needed for the economy to grow (Di Vita 2017), as it reduces uncertainty (Slemrod 2005, Graetz 2007): incomplete laws can be understood as incomplete social contracts (Weisbach 2002, Holtzblatt and McCubbin 2003, Givati 2009).

The empirical evidence on the link between regulation and economic growth has so far been mixed. Some work finds a positive relationship between the volume of legislation and economic growth (Fukumoto 2008, Kirchner 2012). Other work, instead, provides evidence for the negative consequences of regulation, such as higher unemployment and lower income (Botero et al. 2004, Di Vita 2017). More recently, the literature has started to specify the conditions under which regulation may be good for the economy. Gratton et al. (forthcoming) focus on the mediating effect of the political system. Political instability, for instance, may lead to excessive legislative production and backlogging of the bureaucracy. An inefficient bureaucracy that cannot implement legislation in a timely manner, in turn, creates incentives for politicians to propose (poor) legislation just to signal their efforts to voters.1 The result is complex regulation that hurts the economy. As shown in Foarta and Morelli (2020), complexity traps, where complexity begets complexity, are particularly likely when economic crises or technological changes lead to a greater need for reforms, but where at the same time the quality and alignment of interests of reform proposers and/or implementers are relatively low. There is strong empirical evidence that government quality is an important factor in mediating the effect of regulation and reforms on economic development, both in Europe and Africa (Crescenzi et al. 2017, Rodríguez-Pose and Kettere 2019, Iddawela et al. 2021).

In our recent paper (Ash et al. 2020), we provide the first (causally identified) empirical analysis of the effect of legislation on economic growth. By building on the literature on endogenously incomplete contracts (Battigalli and Maggi 2002, 2008), we put forward a series of claims about when and where legislation leads to economic growth.

Theoretically, we conceive drafting legislation as akin to writing contracts. In this vein, legislators regulate the economy in different ways: they can use spot clauses, contingent clauses, or leave full discretion. Contingent clauses are the most complete, as they specify the different states of the world and the different actions that are to be taken but are also the most expensive in terms of drafting, implementing, and monitoring costs. Spot clauses dictate a single course of action, regardless of the state of the world. They are comparatively cheap to draft, implement and monitor, but they are less complete. Finally, discretion is the cheapest option but works only for simple economic interactions. The economy must be regulated by an optimal level of completeness in order to grow. On the one hand, too much complexity will be detrimental for a simple economy as the drafting, implementing, and monitoring costs of regulation will outweigh the economic benefits. On the other hand, a complex economy requires complete legislation that matches all the potential events with the actions performed by economic agents. We expect that contingent clauses are those that drive the effect on economic growth (when well crafted). Moreover, we expect that the link between regulation and economic growth is stronger where the economy is lowly regulated. Finally, further completeness of regulation is required where the economic situation is uncertain, and hence regulation needs to take into consideration all the possible scenarios.

We take these hypotheses to data in the context of the US states for the years 1965 to 2012. First, we measure the level of completeness of legislation and divide statements into contingent and spot statements. We do so using methods in computational linguistics to detect legally relevant clauses from legislation (Vannoni et al. 2020). Then, we use topic modelling, common practice in political economy and political science today, to associate legal statements to policy topics/areas. Finally, we rely on the diffusion of legislation in different policy topics/areas across US states to build an instrument that isolates exogenous variation in legislation.

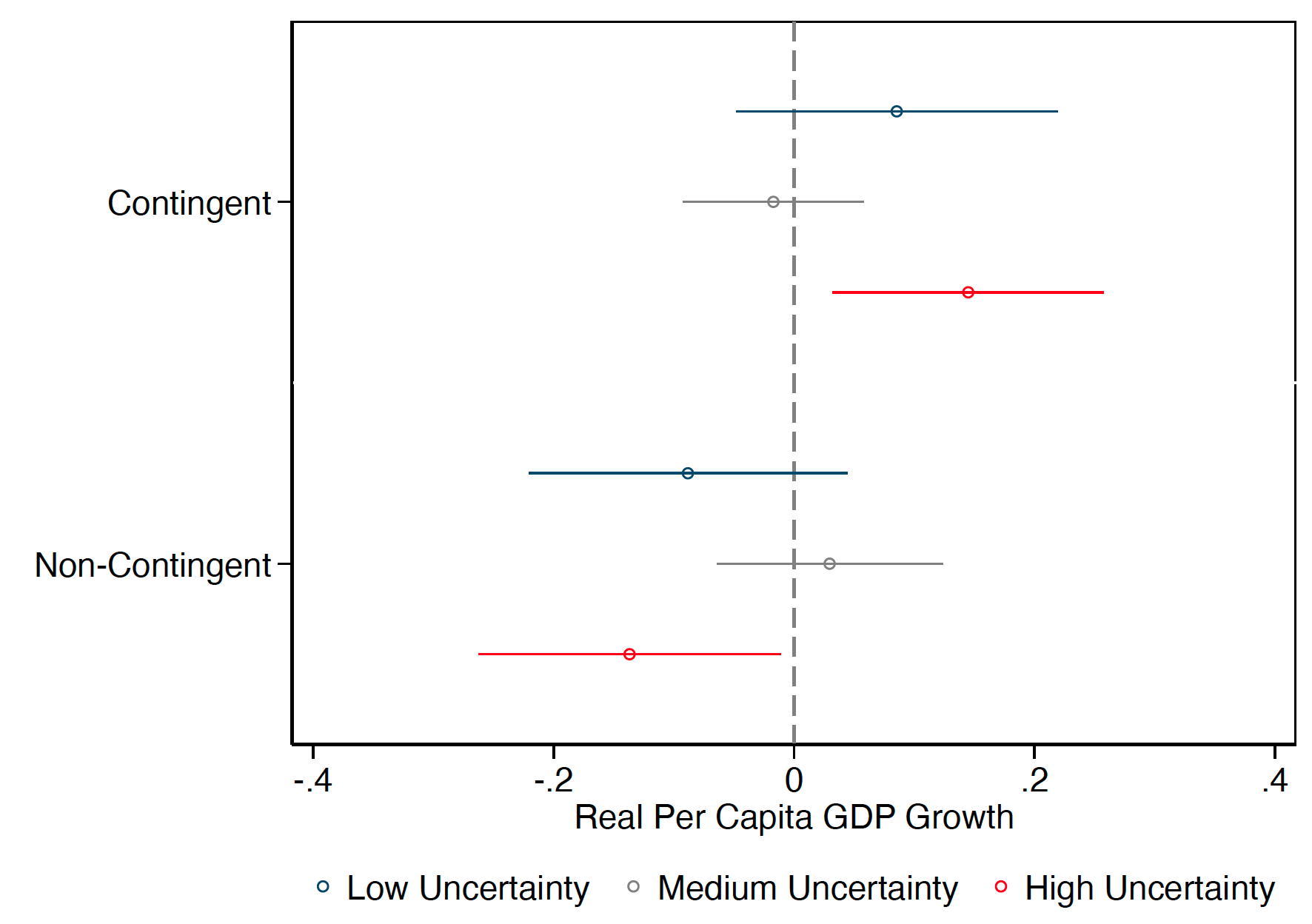

Our findings support the theoretical hypotheses. More contingent legislation leads to more economic growth (as well as wages and profits). This effect is stronger for those states where the initial level of regulation is low and those that face more economic uncertainty. As shown in Figure 1, contingent clauses have a positive effect on the economy only when the uncertainty is high. In these instances, legislators need to draft complete regulation that takes into considerations all the potential actions that need to be taken in all the potential scenarios. In these uncertain times, non-contingent legislation (i.e. the spot clauses discussed above) has negative effects on the economy. Too rigid clauses that do not allow for consideration to different scenarios and actions are detrimental for the economy when there is uncertainty.

Figure 1 Effect of contingent and non-contingent provisions on real per capita GDP growth under low, medium and high uncertainty

The baseline result of ‘more laws, more growth’ is likely specific to the context we look at. In US State level legislation, it is possible to learn from other states’ experiences (through policy diffusion) and regulation is typically designed and implemented by agencies that are of higher quality than in other countries or institutional systems. In countries with lower quality and lower accountability, the effects of greater completeness of the social contract may just be over-complexification, without the benefits detected in this study. The ‘contingent’ nature of the relationship between regulation and growth calls for more research at this time of need for fast reforms.

References

Ash, E, M Morelli and M Vannoni (2021), “More Laws, More Growth? Evidence from U.S. States”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15629.

Battigalli, P and G Maggi (2002), “Rigidity, discretion, and the costs of writing contracts”, The American Economic Review 92(4):798–817.

Battigalli, P and G Maggi (2008). “Costly contracting in a long-term relationship”, The RAND Journal of Economics 39(2):352–377.

Bellodi, L, M Morelli and M Vannoni (2021), “The costs of populism for the bureaucracy and government performance: Evidence from Italian municipalities”, Working Paper.

Botero, J C, S Djankov, R L Porta, F Lopez-de Silanes and A Shleifer (2004), “The regulation of labor”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(4):1339–1382.

Braunerhjelm, P and J E Eklund (2014), “Taxes, tax administrative burdens and new firm formation”, Kyklos 67(1):1–11.

Ciccone, A and E Papaioannou (2007), “Red tape and delayed entry”, Journal of the European Economic Association 5(2-3):444–458.

Crescenzi, R, M Di Cataldo and A Rodríguez-Pose (2017), “Government quality and the economic returns of transport infrastructure investment”, VoxEU.org, 11 April 2017.

Dam, K (2007), The Law-Growth Nexus: The Rule of Law and Economic Development, Brookings Institution Press.

Di Vita, G (2017), “Institutional quality and the growth rates of the Italian regions: The costs of regulatory complexity”, Papers in Regional Science 97(4): 1057-1081.

Foarta, D and M Morelli (2020), "Complexity and the reform process", Working Paper.

Fonseca, R, P Lopez-Garcia and C A Pissarides (2001), “Entrepreneurship, start-up costs and employment”, European Economic Review 45(4):692–705.

Fukumoto, K (2008), “Legislative production in comparative perspective: Cross-sectional study of 42 countries and time-series analysis of the japan case”, Japanese Journal of Political Science 9(1):1–19.

Givati, Y (2009), “Resolving legal uncertainty: The unfulfilled promise of advance tax rulings”, Virginia Tax Review 29(137):169–175.

Graetz, M J (2007), “Tax reform unravelling”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(1):69–90.

Gratton, G, L Guiso, C Michelacci and M Morelli (forthcoming), “From Weber to Kafka: Political activism and the emergence of an inefficient bureaucracy”, The American Economic Review.

Holtzblatt, J and J McCubbin (2003), “Whose child is it anyway? Simplifying the definition of a child”, National Tax Journal 56(3): 701-718.

Iddawela, Y, N Lee and A Rodríguez-Pose, “The (de-) central question: Subnational governments and the making of development in Africa”, VoxEU.org, 21 February 2021.

Kirchner, S (2012), “Federal legislative activism in Australia: a new approach to testing Wagner’s law”, Public Choice 153(3):375–392.

Nicoletti, G and S Scarpetta (2003), “Regulation, productivity and growth: OECD evidence”, Economic Policy 18(36):9–72.

Niskanen, W A (1971), Bureaucracy and representative government, Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Rodríguez-Pose, A and T Ketterer (2019), “Institutional change and development in lagging regions in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 18 November 2019.

Slemrod, J (2005), “The etiology of tax complexity: Evidence from us state income tax systems”, Public Finance Review 33(3):279–299.

Teles, S M (2013), "Kludgeocracy in America", National Affairs 17: 97-114.

Vannoni, M, E Ash and M Morelli (2020), “Legislative information extraction: Methods and application to US state session laws”, Political Analysis 29(1): 43-57.

Weisbach, D A (2002), “An economic analysis of anti-tax avoidance doctrines”, American Law and Economics Review 4(1):88–115.

Endnotes

1 This is confirmed also by Bellodi et al. (2021), who find that Italian populist led municipalities tend to reduce the efficiency of bureaucracy and to propose more legislation.