Some movies feel like a replay. Can we do anything to prevent a sad ending to the current boom-bust cycle, which resembles earlier financial crises? The deal-making engine driving M&As, fuelled by high valuations and cheap leveraged finance, is running at full power.

Central bankers and supervisors warn about overheating to no avail. Supervisors take some action on banking, but that drives business to alternative investment funds. After the Global Crisis, Brunnermeier et al. (2009) warned against this sectoral focus. They called for a system-wide approach to macro-prudential regulation. In earlier work (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015), my co-author and I showed how supervisors could apply a minimum leverage ratio to alternative investment funds (hedge funds, for example) to slow the growth of their balance sheet. This instrument has not – yet – been activated.

Euphoria

Leveraged finance is made up of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds for non-investment-grade firms that are highly indebted. These firms are often owned by private equity. Figure 1 shows that leveraged finance has doubled since the global crisis.

Figure 1 Leveraged finance in Europe and the US (US$ trillion)

Source: BIS (2018).

Moreover, the share of leveraged loans is increasing, just as immediately before the global crisis (Figure 2). Debt financing with thin equity stakes is risky. When the economy turns, equity is quickly wiped out, leading to failure.

Figure 2 Leveraged loans as share of total leveraged finance (%)

Source: BIS (2018).

A final point of worry is the increasing share of covenant-lite leveraged loans, which is rising fast to about 60 to 70% (Figure 3). Increased amounts of financing, plus loosening of standards, are both signs of a boom with strong competition and overtrading. In the search for yield in the current low-interest environment, both banks and investment funds are driving the leveraged finance market.

Figure 3 Covenant-lite leveraged loans (% of leveraged loans)

Source: ECB (2018).

Minsky’s (1986) financial instability hypothesis distinguishes five stages, from boom to bust:

1. credit expansion, characterised by rising assets prices

2. euphoria, characterised by overtrading

3. distress, characterised by unexpected failures

4. discredit, characterised by liquidation

5. panic, characterised by the desire for cash

We are now well into the second stage of euphoria, close to the third stage, in which there is an accident waiting to happen that will cause a collapse of the leveraged finance market, and possibly the wider financial system.

Current sectoral approach

Central banks are warning that current loan volumes and loose standards are not sustainable (Bank of England 2018, ECB 2018, Goel 2018). But nobody is listening. Business continues as long as the music plays.

Supervisors give guidance to banks, for example, that a company’s gross debt should not exceed six times its EBITDA. But they are not addressing non-bank financial intermediaries, such as insurers, pension funds, investment funds, hedge funds, and private equity. The Bank of England (2018) shows that about one-third of leveraged loans are held by banks, one-third by insurers, and pension funds and the remaining one-third by hedge funds and open-ended investment funds.

As we would expect in differing sectoral regulations (Cizel et al. 2019), there is anecdotal evidence that leveraged finance business is moving to non-banks in response to tightening banking requirements. There is therefore a need for a sector-wide approach.

System-wide approach

In earlier work (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015), my co-author and I showed how a minimum leverage ratio could slow the growth of the balance sheet of financial intermediaries. With a fixed leverage ratio (i.e. equity/total assets), equity is the constraining factor for growth of total assets.

Banks (and insurers) face such a leverage ratio. The Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (2011/61/EU) enables supervisors, among other things, to maximise the leverage of investment funds, including hedge funds and private equity. A maximum leverage requirement (where leverage equals debt/equity) is equivalent to a minimum leverage ratio (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015).[1]. A minimum leverage ratio of 5% is, for example, equivalent to a maximum leverage of 19.

So far, securities supervisors have not activated this leverage requirement for investment funds. A major problem for sectoral regulation is that different supervisors follow different approaches, each one using the language that sector, and so are not aware of similarities. Non-bank supervisors also tend to be more lenient than bank supervisors on the prudential front.

Macroprudential supervision needs to be applied system-wide to avoid regulatory leakages (Cizel et al. 2019). First, we propose to maximise leverage of investment funds that are involved in leveraged finance, through collateralised loan obligations or high-yield bonds. This forces securities supervisors to use the powers they have. Second, the guidance on leveraged finance for the borrowing companies (gross debt should not exceed six times EBITDA) should be given to all suppliers of finance. In the Netherlands, we have good experience with applying borrower-based requirements (such as maximum loan-to-value ratios for mortgages) to all financial intermediaries.

A cross-sectoral approach could help macroprudential authorities to rein in the current unsustainable levels of leveraged finance.

References

Bank of England (2018), Leveraged Lending, Financial Stability Report, November: 42-48.

Brunnermeier, M, A Crockett, C Goodhart, A Persaud, and H Shin (2009), The Fundamental Principles of Financial Regulation, Geneva Report on the World Economy 11, ICMB and CEPR.

Cizel, J, J Frost, A Houben, and P Wierts (2019), "Effective macroprudential policy: Cross-sector substitution from price and quantity measures", Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, forthcoming.

ECB (2018), "Disorderly increases in risk premia remain a prominent risk to euro area financial stability", Financial Stability Review, November: 51-65.

Goel, T (2018), "The rise of leveraged loans: a risky resurgence?", BIS Quarterly Review, September: 10-11.

Minsky, H P (1986), Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, Yale University Press.

Schoenmaker, D and P Wierts (2015), "Regulating the Financial Cycle: An Integrated Approach with a Leverage Ratio", Economics Letters 136: 70-72.

Endnote

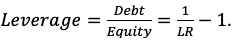

[1] The minimum leverage ratio is as follows:

The maximum leverage is related to the leverage ratio as follows: