Leaving the office to work from home in spring 2020 was surprisingly easy. Almost immediately, workers began to work remotely using their own homes as workplaces in an attempt to carry on working while socially distancing due to COVID-19 (Davis et al. 2021a). Data show that 35% and 50% of workers were working from home in the US and some major European countries (Bick et al. 2020, Brynjolfsson et al. 2020, Buchheim et al. 2020, Aneyi et al. 2021).

Initially, productivity at home was lower than productivity at work in normal times (Bartik et al. 2020, Morikawa 2021). But jobs could be performed at home (Dingel and Neiman 2020), and employers got better at working from home, learning how to use the technology available in the 2020s. Compared to what might have happened a couple of decades earlier without affordable ICT equipment, fast internet connections and, most recently, videoconferencing software, the shift was surprisingly manageable.

Davis et al. (2021b) argue that the pandemic accelerated the widespread adoption of technologies used when working from home. This raised the relative productivity of working at home, particularly compared to the awkward and costly arrangements (e.g. personal protective equipment, hand sanitiser, social distancing) of working at the business premises.

A year or more after we first made the leap to working from home, employees like to work from home (Barrero et al. 2020a, Taneja et al. 2021) and returning to the office will be hard.

The May 2021 update of our survey (Taneja et al. 2021) of 2,500 working-age employees reveals what we have been hearing from dozens of firms. Firms and organisations are increasingly reporting major challenges persuading employees to come back to the office, driven in part by the surging labour market. We see that more than 70% of UK employees want to work from home 2+ days a week (see Figure 1) with similar figures in the US (Barrero et al. 2020b).

Figure 1 In 2022, how often would you like to have paid workdays at home?

Part of this is due to the relaxed atmosphere when working from home, with informal clothing and flexibility in balancing work and home chores, and the reluctance to get back into a 9-5 routine with the hassle of commuting. Workers don’t want to go back to ‘hard pants’ (Clark 2021a).

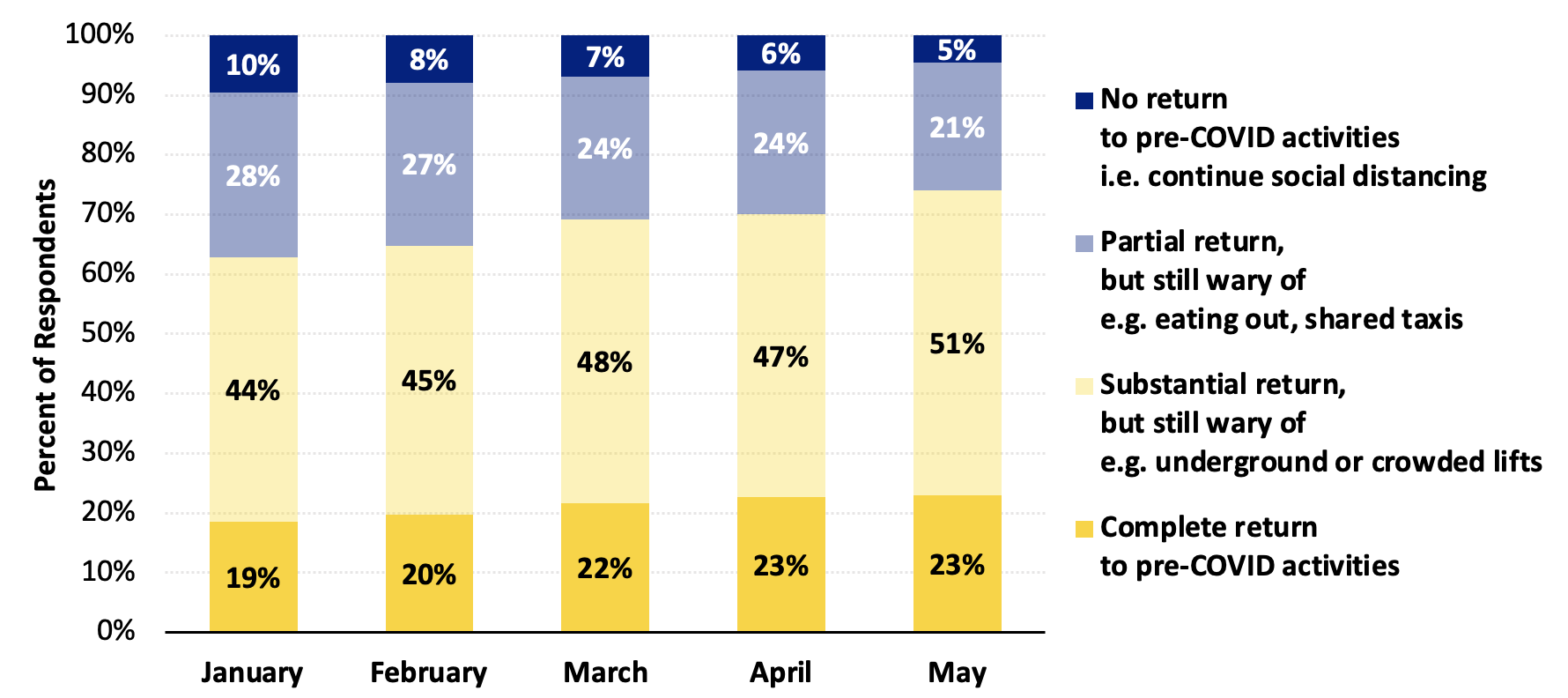

Another issue that is impeding the return to the office is a continued fear of crowding. Large numbers of respondents report fears of being close to their co-workers and fellow commuters. It may seem these worries are overblown – surely once everyone is vaccinated these concerns will pass?

Possibly, although precedents like the three-year lull in air traffic after the 9/11 terrorist attacks do not bode well. Our data suggest a large plurality of employees will be extremely hesitant to return to the office post-pandemic, making it harder still to achieve a return to the office for large firms.

Figure 2 Views on social distancing if a COVID-19 vaccine is approved

Complicating this further is what every manager has been fearing (Clark 2021b) – that, given a choice, most employees will take Monday and Friday off (Figure 3). Indeed only 36% of employees would come in on Friday, compared to 82% on Wednesday. This highlights the severe problems firms could face over the effective use of office space if they let employees pick their days to work from home. Providing enough desks for every employee coming in on Wednesday would leave most of these desks empty on Monday and Friday.

Efficient office space use will require coordination

Question: “If you got to work from home for two days per week, which two days would you choose?”

Figure 3 Preferred work-from-home days

Of course, to fix this peak-load problem, firms could centrally allocate days for each employee or each team to work from home. Indeed, this advice to centrally set work-from-home patterns is the advice we have been giving to firms (Bloom 2021a). But our survey highlights how even this could create challenges.

Those missing out on the coveted Monday and Friday work-from-home days could feel mistreated. Should CEOs and HR groups decide this by lottery, missing out on the chance to pick overlapping days for teams that work closely together? Or should they centrally decide work-from-home days and risk claims of favouritism when some team gets given Tuesday and Wednesday? Or might firms want to rotate work from home days every few months so all employees have an equal share of different days over the year? This would seem fairer but would complicate business and personal scheduling.

Interestingly, drilling into the data, we also see different groups have varying strengths of feelings over working from home on Monday and Fridays (Figure 4). Men with children are the group most focused on working from home Monday and Friday, while women with children are the most balanced across the week. Maybe fathers are planning long weekends away with (or without) their kids? Since we did not ask for the reasons for the choice of days, it is hard to know – but it highlights many of the complexities in planning the return to the office.

Men with children are most focused on work from home on Monday/Friday

Figure 4 Preferred work from home days for people with children, by sex

One other consideration from the May survey highlights why returning to the office, at least for a few days each week, is important: the need to run some activities in person – particularly, larger meetings. We asked respondents to our survey how they found the efficiency of meetings by video call compared to in person (Figure 5).

Large meetings in particular are better in person

Question: “How do meetings compare by videocall (Zoom, Teams, etc.) versus in person in terms of how efficient the meetings turn out to be?”

Figure 5 Difference in efficiency of videocall versus in-person meetings, by meeting size

As you might guess, the data suggest that small meetings of two to four people are about as efficient by video call as in person. In-person meetings are typically easier for making personal connections and communicating, with the ability to make more visual cues and gestures. But in-person meetings require some travel time and present infection risk during pandemic times and potentially room-booking logistics.

Since a video call with two to four people means everyone occupies a large box on their Zoom screen, it is easy for everyone to speak. With few people on the call, it is also possible to meet without muting, so it is easier to have a flowing conversation. Hence the choice between video calls and in-person meetings is pretty balanced.

In contrast, almost half of all respondents reported large 10+ meetings were worse by video call, with only a quarter reporting they were better. Large meetings are harder by video call. Individuals are allocated to small boxes so it is hard to see the faces of the participants. People typically have to mute themselves because with large groups, there is always somebody whose neighbour is using a leaf blower or whose kids are practising the trumpet. And we hear from firms that large meetings can be hijacked by one or two vocal individuals.

When asked whether holding meetings by video calls had improved or reduced their overall efficiency, those respondents that answered positively indicated that the main benefit had been better time management. Individuals responding negatively cited the difficulties of accessing side conversations and the difficulty of communicating online, which is more problematic if there are many large group meetings.

As such, the advice to move to a hybrid working week seems appropriate (Bloom 2021b). Two or three days a week at home for quiet time and small meetings of two to four people; the remaining days in the office for social events, larger meetings, informal communication, and building company culture – this is becoming the norm for many businesses. Indeed, the tightness in the labour market means that some firms may never get their employees to return to the office without this.

References

Anayi, L, N Bloom, P Bunn, P D Mizen, M Oikonomou, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2021), “Update: Which firms and industries have been most affected by COVID-19?”, Economic Observatory, 5 May.

Barrero, J, M, N Bloom and S Davis (2020a), “60 million fewer commuting hours per day: How Americans use time saved by working from home”, VoxEU.org, 23 September.

Barrero, J, M, N Bloom and S J Davis (2020b), “COVID-19 and labour reallocation: Evidence from the US”, VoxEU.org, 14 July.

Bartik, A W, Z B Cullen, E L Glaeser, M Luca and C T Stanton (2020), “What jobs are being done at home during the COVID-19 crisis? Evidence from firm-level surveys”, NBER Working Paper 27422.

Bick, A, A Blandin and K Mertens (2020), “Work from home after the COVID-19 outbreak”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15000.

Bloom, N (2021), “Don’t let employees pick their WFH days”, Harvard Business Review, 25 May.

Bloom, N (2021b), “Our research shows working from home works, in moderation”, Guardian, 21 March.

Brynjolfsson, E, J J Horton, A Ozimek, D Rock, G Sharma and H-Y TuYe (2020), “COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data”, NBER Working Paper 27344.

Buchheim, L, J Dovern, C Krolage and S Link (2020), “Firm-level expectations and behavior in response to the COVID-19 crisis”, IZA Discussion Paper 13253.

Clark, P (2021a), “Don’t make me go back to hard pants five days a week”, FT.com, 6 June.

Clark, P (2021b), “Empty offices on Mondays and Fridays spell trouble”, FT.com, 16 May.

Davis, M A, A C Ghent and J M Gregory (2021a), “The work-from-home technology boon”, VoxEU.org, 18 April.

Davis, M A, A C Ghent and J M Gregory (2021b), “The work-at-home technology boon and its consequences”, working paper, Rutgers University.

Dingel, J, and B Neiman (2020), “How many jobs can be done at home?”, NBER Working Paper 26948.

Morikawa, M (2021), “The productivity of working from home: Evidence from Japan”, VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Taneja, S, P D Mizen and N Bloom (2021), “Working from home is revolutionising the UK labour market”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.