US government employees often find themselves in a peculiar situation which involves monitoring, regulating, and even disciplining the behaviour of firms whom they hope to later work for. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, the safety of a new drug may be determined by a Food and Drug Administration employee who soon after joins the firm that developed it. In financial services, the penalty for fraud may be determined by a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) employee who is subsequently hired by the bank that perpetrated it. These cases pose clear conflicts of interest, but they are hardly unique. Workers move so frequently between agency and industry positions that they are said to pass through ‘revolving doors’ as they move from public- to private-sector roles.

Long before ‘draining the swamp’ became a campaign position of the current US administration, economists raised concerns that lax regulation might be exchanged for lucrative subsequent employment, resulting in agencies that serve the interests of industry over the very public they were designed to protect (Peltzman 1976, Stigler 1971). The scale and scope of the problem, though, was largely unknown, though this is starting to change.

Evidence from examiners

In recent work (Tabakovic and Wollmann 2018), we study patent examiners employed by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Examiners decide how much, if any, protection to grant inventors over their ideas by evaluating the claims made in their applications. The majority of these applications are filed by law firms specialising in intellectual property, many of whom frequently hire former examiners. Transitions from the USPTO to filing firms are hardly surprising – turnover among government employees is high, and law firms house the jobs for which former examiners are best suited. They do, however, create an awkward situation. Many examiners wind up evaluating the applications of firms for whom they hope to work. Patents impact many dimensions of the economy ranging from investment (Budish et al. 2015) and labour income (Kline et al. 2017) to entrepreneurial activity (Farre-Mensa et al. 2017) and the rate of innovation (Moser 2005), so if examiners’ impartiality is compromised, it is a big problem.

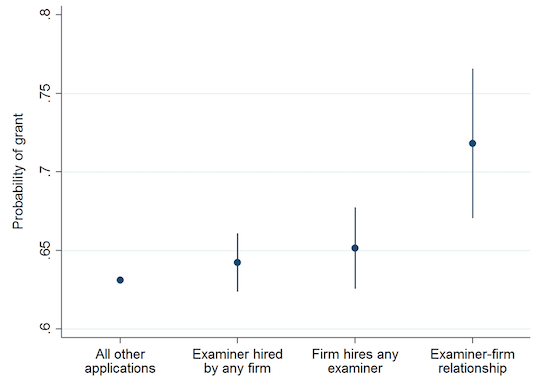

What do the data indicate? First, examiners grant considerably more patents to the firms that ultimately hire them. This fact alone does not imply examiners are ‘captured’, but comparisons among the over one million applications rule some alternative explanations out. For example, the difference is not driven by whether some examiners are more generous overall or whether certain firms are, on average, more successful. Other factors suggest that examiners’ individual preferences for one firm over another, or one type of technology over another, do not drive these results. For example, one might worry that an examiner who is more enthusiastic about engines than semiconductors or cell phones will not only grant more engine-related patents but also tend to work at the firms who specialise in them. Yet, examiners assess only narrowly defined types of technology.

Figure 1 Examiners grant more patents to firms that hire them

Note: This figure plots the coefficients that result from regressing the probability that a patent application is successful on indicators for whether the examiner was hired by any filing firm, whether the filing firm hired any examiner, and whether the filing firm hired the examiner assessing the particular application. The left-most point reflects the constant term, which is added back to the coefficients for comparison’s sake. The specifications include calendar year and patent class fixed effects, though the relative magnitude and significance of the main coefficient of interest – the final one – is robust to including examiner and firm fixed effects as well.

Source: Tabakovic and Wollmann (2018).

Second, when we plot the main effects over time, we find that the differences are much larger in periods when firms are frequently hiring. During the dot com bust or Great Recession, for example, the leniency that examiners extend future employers disappears. Coming out of these hiring troughs, examiner leniency reappears.

Third, we find leniency can be tied to factors determined priorto the examiners joining the USPTO. For example, we show that the geographic location of an examiner’s alma mater predicts where he or she will later work. We then show that examiners who leave the agency grant significantly more patents to this predicted set of firms. One might worry that this merely reflects ‘home bias’ – i.e. favourable treatment for firms close to areas where one grew up or attended school. However, the effect is completely absent among employees who stay at the agency.

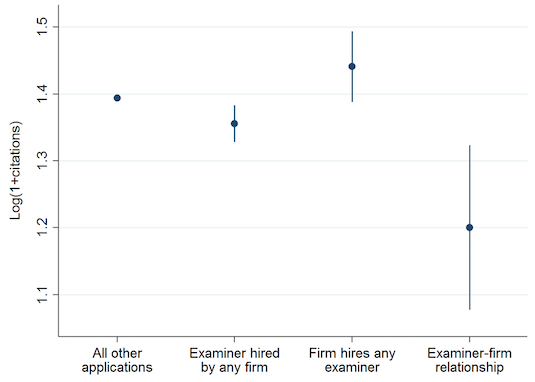

Ultimately, this leniency lowers the quality of patents coming out of the agency, which we measure using citations. For example, patents granted to firms that later hire the examiner who assessed them received about 25% fewer citations, consistent with the idea that these firms’ applications are held to a lower standard.

Figure 2 Patents granted to subsequent employers are of lower quality

Note: This figure plots the coefficients that result from regressing the log of one plus the number of citations a patent receives on indicators for whether the examiner was hired by any filing firm, whether the filing firm hired any examiner, and whether the filing firm hired the examiner assessing the particular application. The left-most point reflects the constant term, which is added back to the coefficients for comparison’s sake. The specifications include calendar year and patent class fixed effects, though the relative magnitude and significance of the main coefficient of interest – the final one – is robust to including examiner and firm fixed effects as well.

Source: Tabakovic and Wollmann (2018).

Policy considerations

While these results raise doubts about examiner impartiality, they are silent on what policymakers should do about it. Hasty policy changes can have large, unintended consequences in these settings. Several options have been discussed.

Can’t we simply ban examiners from joining law firms for a year or two after leaving, i.e. create a ‘cooling off’ period similar to that which members of Congress or partners at US accounting firms face? This is unclear. Such post-employment restrictions can dissuade talented individuals from joining agencies in the first place, or deprive them of incentives to work hard and ‘show off’.

In fact, recent work by Kempf (2018) substantiates precisely that concern, albeit in a different setting. She studies credit analysts at US rating agencies, tying together data on how they graded various financial products and who later hired them. Prior work showed analysts biased ratings in the direction of their future employers (Cornaggia et al. 2016) – a big problem, since inaccurate ratings may be partly to blame for the financial crisis. Kempf points out, though, that analysts who leave the agencies to join investment banks are much more accurate overall. Even more striking, as the probability that an analyst will be hired by an investment bank rises, their accuracy increases. Perhaps agencies need to permit some corruption to gain some competence. It’s an unsavoury idea, but we live in an imperfect world.

What about monitoring examiner-attorney interactions and punishing the sort of quid pro quo exchanges that made former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich so famous?1 Besides cost and privacy concerns, it is important to remember that regulatory capture requires no explicit agreements at all. Nothing in our data, for example, implies these were ever discussed. In fact, we think very rarely, if ever, does this happen. Industry norms are sufficient – simply following the principle that one should not ‘bite the hand that feeds it’, so to speak, will suffice.

Couldn’t we instead just ‘blind’ the process, withholding the examiners’ identities from the firms? While some agencies might make this work, in most cases this is not practical. Frequent interactions are required. Regulated firms will eventually figure out who their regulator is.

These issues aside, it is also unclear how one agency’s experience applies to another’s. For example, deHaan et al. (2015) find that private law firms defending companies targeted by the SEC hire prosecutors that are harsher overall. The cause is unclear. Perhaps talent is showcased with toughness in the adversarial process of litigation, and defence firms hire the best litigators, or perhaps defence firms hire the prosecutors they simply do not want to face again. Equally provocative, the authors find that the opposite is true for SEC lawyers based in Washington, DC, at least where criminal investigations are concerned.

Future research

In our view, revolving doors can present a serious problem, but policymakers need more guidance. Fortunately, as social networks offer increasingly comprehensive data on worker transitions and governments continue to experiment with post-agency employment restrictions, opportunities will arise frequently for careful academic research to contribute to the debate.

References

Budish, E, B N Roin and H Williams (2015), “Do firms underinvest in long-term research? Evidence from cancer clinical trials”, American Economic Review 105(7): 2044-2085.

Cornaggia, J, K Cornaggia and H Xia (2016), “Revolving doors on Wall Street”, Journal of Financial Economics 120(2): 400-419.

Kempf, E (2018), “The job rating game: The effects of revolving doors on analyst incentives”, SSRN working paper.

Kline, P, N Petkova, H Williams and O Zidar (2017), “ Who profits from patents? Rent-sharing at innovative firms”, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California Berkeley working paper 107-17.

Farre-Mensa, J, D Hegde and A Ljungqvist (2017) “What is a patent worth? Evidence from the US patent ‘lottery’”, NBER working paper 23268.

Moser, P (2005), “How do patent laws influence innovation? Evidence from nineteenth-century world’s fairs”, American Economic Review 95(4): 1214-36.

Peltzman, S (1976), “Toward a more general theory of regulation”, Journal of Law and Economics 19(2): 211-240.

Stigler, G J (1971). “The theory of economic regulation”, Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1): 3-21.

Tabakovic, H and T G Wollmann (2018), “From revolving doors to regulatory capture? Evidence from patent examiners”, NBER working paper 24638.

Endnotes

[1] Blagojevich was convicted and sentenced to federal prison for auctioning political appointments, including the US Senate seat vacated by Barack Obama. With respect to that position, wiretaps by the Federal Bureau of Investigation revealed that Blagojevich was unwilling to merely ‘give up [the seat] for nothing’ because he believed it was ‘golden’, i.e. valuable.