This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU debate on "Populism"

The recent surge in populist, authoritarian and far-right movements in advanced and emerging economies has revived a long-existing debate on the role of economic and cultural factors in explaining political extremism. Indeed, the ongoing Vox debate on populism offers a lively discussion on this issue. Building on the ‘cultural backlash theory’ of Norris and Inglehart (2019), Eichengreen (2019) shows that, in the case of Brexit, economic conditions are as important as cultural identity in explaining the results of the referendum. Rodrik (2019) argues that the interaction between economic shocks and cultural values is often crucial to explain a populist backlash. Economic shocks, which are sudden and short-lived, can trigger populist support along existing cultural divides, which are deep-seated and slow moving. While it may be tempting to search for common cultural and economic forces that explain the rise of populism throughout the world, Colantone and Stanig (2019) emphasise that populist parties have very diverse political platforms and cannot be understood in isolation of their national contexts.

So far, all contributions to this Vox debate have focused on advanced economies: US, UK (Brexit), and other Western European countries. In this column, we broaden the debate by discussing the Brazilian election of October 2018, when far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro was elected president.

Populism in Latin America: A turning point?

In contrast to the ongoing surge in populism in advanced economies, which is often right-wing, Latin American populism has been mostly associated with the left.1 Dornbusch and Edwards (1991) define Latin American “macroeconomic populism” as a set of unsustainable economic policies arising from the tension between inequality and redistribution. Recently, Edwards (2019) shows that nearly all populist governments in Latin America, both before and after the 1990s, were characterised by “charismatic leaders” that pursued heterodox economic policies. Bolsonaro’s election represents a turning point in the region. In contrast to the ‘old’ Latin American populist agenda, which was mainly restricted to the economic sphere, Bolsonaro spearheaded an authoritarian and ultra-conservative platform, aptly labelled by Hunter and Power (2019) as an “illiberal backlash”. This development is consistent with Tabellini’s (2019) description of a shift from political cleavages based on class distinction towards a clash along cultural dimensions.

In a recent paper, we investigate how a large economic shock in Brazil triggered support for Bolsonaro along a particularly pervasive and entrenched cultural cleavage, namely the norms surrounding gender identities (Barros and Santos Silva 2019).

Brazil: The 2014-18 economic crisis, gender, and the 2018 presidential election

Although posing as an outsider, Jair Bolsonaro, a former Captain for the reserve army, has a long career in politics. Between 1991 and 2018, he was elected seven consecutive times as federal deputy for the lower chamber of Congress. Throughout this period, Bolsonaro became known to the public for views that are widely considered as sexist, homophobic, racist, and, overall, illiberal. Unlike right-wing populist movements in the US and Europe, whose rhetoric focuses mostly on immigration, a substantial amount of Bolsonaro’s illiberal views concerned gender issues, often reflecting misogynous beliefs. In one episode, back when Bolsonaro was a federal deputy, he stated to a female colleague, during a debate, that he would not rape her because “she was not worth it”. In 2016, when interviewed in a television show, Bolsonaro said that he would not hire a woman with the same wage as a man because “women get pregnant”. More recently, after being elected, Bolsonaro made offensive comments on social media about the appearance of Brigitte Macron. Since women make up roughly 52% of the Brazilian electorate, understanding his electoral support in spite of his hostility towards such an important demographic group is not straightforward. We argue that this apparent contradiction can be resolved by conciliating the literature on relative social status (e.g. Gidron and Hall 2017), gender identity (e.g. Akerlof and Kranton 2000, Bertrand et al. 2015), and recent research exploring the economic roots of populism (e.g. Colantone and Stanig 2018, Fetzer 2019). In our work, we show that the labour market effects of the Brazilian economic crisis partially explain support for Bolsonaro. Crucially, however, these results are not driven by the overall economic shock itself, but rather by its differential effects for men and women.

Between 2002 and 2016, Brazil was ruled by the left-wing Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT). The period 2002–2013 was marked by sustained economic growth, large increase in social spending, and rapidly falling poverty and inequality. However, this virtuous cycle came to an end in late 2014, when the Brazilian economy was hit by a severe economic crisis, culminating in two deep recessions in 2015 and 2016. The crisis arose from a complex combination of factors, including a fall in commodity prices, policy mismanagement, and widespread political and economic uncertainty in the wake of the Lava Jato (Car Wash) corruption scandal (Spilimbergo and Srinivasan 2018, Hunter and Power 2019). The main consequence of the crisis for the average Brazilian was a steep rise in unemployment (from 6.8% in the third quarter of 2014 to 11.9% in the third quarter of 2018).

Not all industries were similarly hit by the crisis and, depending on the pre-crisis composition of local employment, the shock affected some regions more than others. Since, in addition, the Brazilian labour market has a great amount of sectoral segregation by gender, the intensity of the shock was different for men and women. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows our shock measure disaggregated by gender and the difference in shock for males and females with darker areas suffering larger employment losses. Our shock variable is measured as a weighted percentage change in employment.

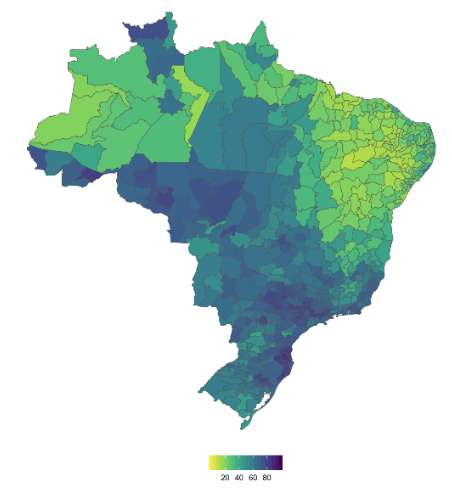

We use this spatial variation to estimate the local impact of the 2014-18 economic shock by gender on local electoral outcomes in 2018. (In technical terms, we use a shift-share approach in the spirit of Bartik 1991 for causal identification.) Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution of the main outcome variable: the percentage of votes for Bolsonaro on the runoff round of the election, disputed with the left-wing PT candidate, Fernando Haddad.

Figure 1 Economic shock for men (top-left), women (top-right) and male-female difference in shock (bottom)

Note: The shock is measured as a weighted percentage change in employment. Higher values mean a stronger shock, i.e. a larger employment loss between 2013 and 2018. Each unit (microregion) represents a local labour market. N= 558 microregions.

Sources: Census 2010, PNAD Contínua (both from IBGE).

Figure 2 Percentage of votes for Jair Bolsonaro (PSL) on the runoff round of the presidential election (28 October 2018)

Note: Each unit (microregion) represents a local labour market. N= 558 microregions.

Sources: TSE.

The empirical analysis reveals that in regions where men experience larger economic shocks, the share of votes for Bolsonaro is higher. In contrast, in regions where women experience larger shocks, his vote share is relatively lower. How large are these effects? In counterfactual exercises, we show that if the male employment shock had, on average, occurred at its maximum observed value, Bolsonaro would have been elected already in the first round of the election. In contrast, if the female shock were, on average, above the 90th percentile of the male shock distribution, Bolsonaro would have lost the second round to Fernando Haddad, which reflects the outcome significance of our results. As pointed out by Margalit (2019), this type of identification strategy only allows us to explain variation across regions in this particular election, not the secular change in populist support. Benchmarking our results with the average change in electoral support, therefore, gives us an idea of the explanatory significance of our results. For the male and female shocks, the standardized effect corresponds to 10% and 13%, respectively, of the average loss in support for the Workers’ Party in the first round. Therefore, although gender norms and economic shocks alone cannot explain the election of Bolsonaro, their effects seem to be important to understand the rise of populism in Brazil.

Because official election results are not disaggregated by gender, we cannot show decisively that these effects come about from men and women voting differently. To do so, we analyse comparable surveys on political preferences, covering 2007-2019.

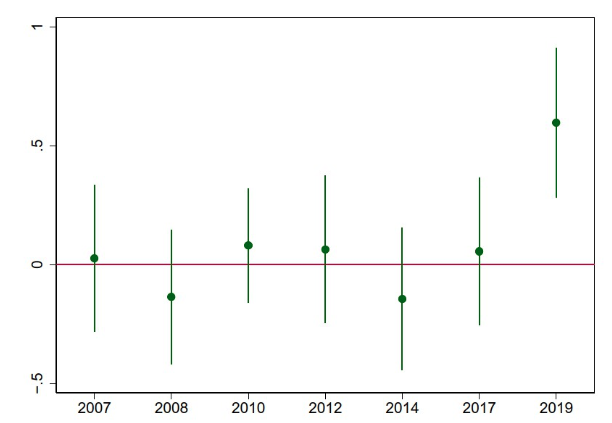

The survey data suggest that the rise of Bolsonaro is closely linked to the emergence of an unprecedented ideological gender gap. Figure 3 plots the evolution of the average male-female difference in a self-reported left-right ideological scale. Higher values on the scale represent a more right-wing ideology. Thus, point estimates above zero mean that, on average, men are more right-wing than women. This is case for 2019, the first survey conducted after Bolsonaro’s victory in the Presidential election. In all previous years, the gender gap in ideology is much smaller and, in fact, statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Figure 3 Male-female gap on the left-right ideological scale (10 point-scale with 0 being the most left-wing value, and 10 the most right-wing value)

Note: Male dummy coefficient shown with 95% confidence intervals, conditional on standard socio-economic control variables and state dummies.

Source: LAPOP (2007-2019).

We hypothesise that Bolsonaro’s authoritarian and sexist rhetoric may be appealing to men who, due to the economic shock, experience a relative loss in traditional masculine, breadwinner-type social identity. This ‘compensation mechanism’ is in line with the literature on the role of the loss of relative social status in the recent rise of populism. For instance, when dominant groups perceive a threat to their status, they rally behind conservative, right-wing and authoritarian candidates who promise to restore the ‘glorious past’ (Mutz 2018, Gidron and Hall 2017, Ballard-Rosa et al. 2019).

A (bleak) outlook

The election of Jair Bolsonaro represents a tectonic shift in Brazil’s political landscape, the consequences of which are likely to be felt for many years to come. Although his government is effectively constrained by a fragmented Congress and the recent divorce between Bolsonaro and his (former) party, the effects on institutions and political norms can be long-lasting.

More generally, Brazil’s 2018 election offers a cautionary tale of how, during economic downturns, social norms of masculinity, which are typically centred around men’s economic status, can become a fertile ground for populism. Policymakers and academics should pay attention to these norms in their analyses and design of policies, if they wish to cut off the ties binding economic insecurity to extreme political choices.

References

Akerlof, G A and R E Kranton (2000), “Economics and identity”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (3): 715–753.

Ballard-Rosa, C, Jensen, A and K Scheve (2019), “Economic decline, social identity, and authoritarian values in the United States”, Unpublished paper.

Barros, L and M Santos Silva (2019), “#EleNão: Economic crisis, the political gender gap, and the election of Bolsonaro”, Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research, Discussion Paper No. 242.

Bartik, T J (1991), Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? ,WE Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Bertrand, M, E Kamenica, and J Pan (2015), “Gender identity and relative income within households.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(2): 571–614.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2018), “Global competition and Brexit”, American Political Science Review 112(2): 201–218.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2019), “Heterogeneous drivers of heterogeneous populism”, VoxEU.org, 10 December.

Dornbusch, R and S Edwards (eds.) (1991), The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, University of Chicago Press.

Edwards, S (2019), “On Latin American Populism, and Its Echoes around the World”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(4): 76-99.

Eichengreen, B (2019), “The two faces of populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Fetzer, T (2019), “Did austerity cause Brexit?” American Economic Review 109(11): 3849–86.

Gidron, N and P A Hall (2017), “The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right”, The British Journal of Sociology 68: S57–S84.

Hunter, W and T J Power (2019), “Bolsonaro and Brazil’s illiberal backlash”, Journal of Democracy 30(1): 68–82.

Kaufman, R R and B Stallings, (1991), “The political economy of Latin American populism”, in The macroeconomics of populism in Latin America, University of Chicago Press: 15-43.

Margalit, Y (2019), “Economic Insecurity and the Causes of Populism, Reconsidered”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(4): 152-70.

Mutz, D C (2018), “Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(19): E4330–E4339.

Norris, P and R Inglehart (2019), Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism, Cambridge University Press.

Rodrik, D (2019), “Many forms of populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Spilimbergo, A and K Srinivasan (eds.) (2018), Brazil: Boom, bust, and the road to recovery, IMF.

Tabellini, G (2019), “The rise of populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Endnotes

[1] There has been some discussion in the literature on whether the right-wing military dictatorships in Latin America should be classified as populist or not (e.g. Kaufman and Stallings 1991, Edwards 2019).